East Bay’s mysterious rock walls: Paranormal? American Stonehenge? Theories abound

If walls could speak, what a tale these mysterious huge boulders would tell. Perched high atop the lonely, windswept ridges of the Diablo Range, chains of stacked stones stand sentry above East Bay cities — yet they delineate nothing.

Long the subject of intrigue — Who built them? Why? How? — the walls are now being mapped by a San Francisco State archaeologist who believes they hold important clues to early California history and deserve our attention and protection.

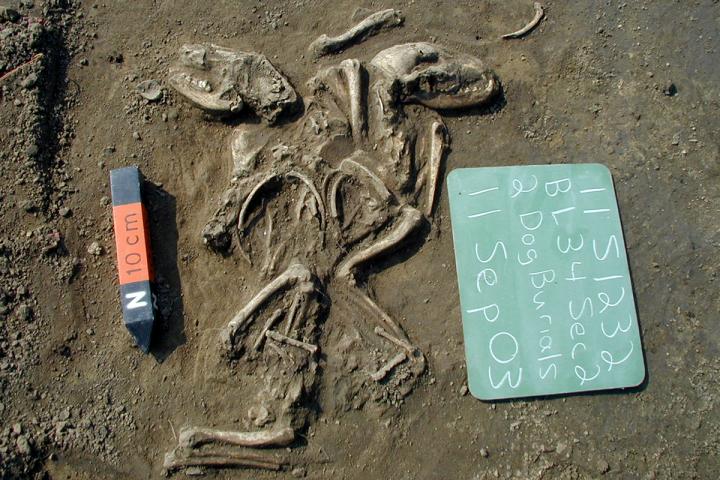

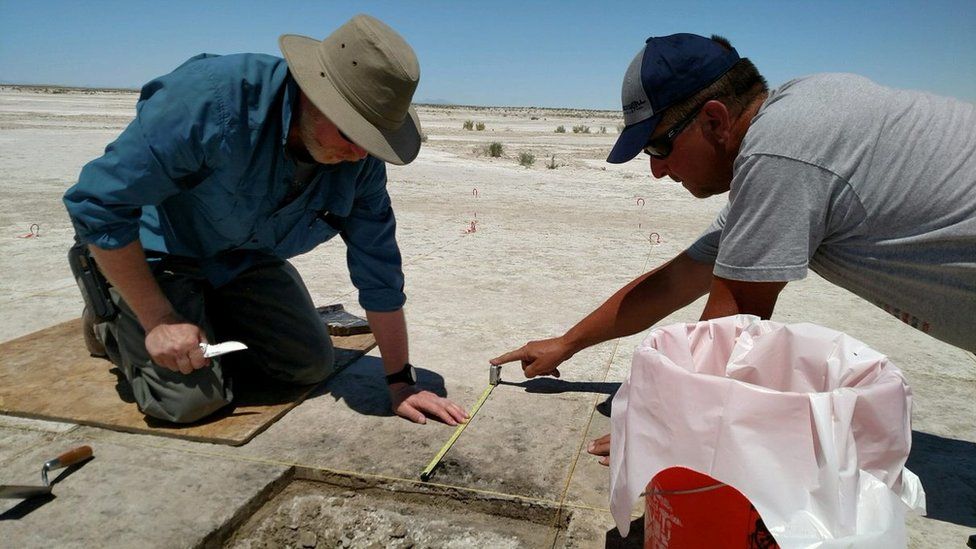

“They are historic sites,” said Jeffrey Fentress, who is measuring and mapping them for the East Bay Regional Park District, then submitting his findings to the California Office of Historic Preservation. “By recording the walls, they become a permanent part of the state archive and are protected — as well as they can be — from future development.”

There are no written or photographic records of their construction in a landscape that has been inhabited by humans for at least 7,000 years. So, like the fabled crop circles of England, the walls have inspired theories ranging from the paranormal to the historically bizarre.

“There is no definitive answer on its origins, which further delights the public, who can take it to new levels of speculation,” said Mark Hylkema, archaeologist for the Santa Cruz District of California State Parks.

New Age mystics have declared that their builders were creatures from a vanished Pacific island; amateur historians suggest that they were Mongols or West Africans. Some theorize that the walls offered defence from intruders; others believe they played a peaceful and spiritual or astronomical role, perhaps serving as a “solstice site” like Stonehenge.

Sections of walls are scattered atop Santa Clara County’s Ed Levin County Park, the Russian Ridge in the Santa Cruz Mountains, several parks within the East Bay Regional Park District and a few private ranches in the Livermore Valley. Some also can be seen in the Sierra foothills, along state Highway 50 past El Dorado Hills.

While well known to the region’s hikers, park officials are reluctant to disclose precise locations because they fear they will attract vandals. A large stone circle on Pleasanton Ridge was destroyed by real estate development in the 1990s.

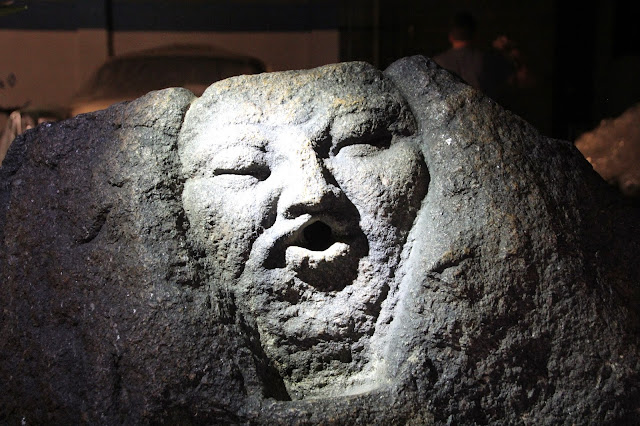

Standing 3- to 4-feet high and wide, they’re sturdy yet unsecured by mortar. They seem too low to offer much protection, or confine horses. Some rocks are melon-size. The larger ones weigh up to a ton. Lifting them no doubt required the effort of several men.

“Some go in a straight line, others twist like a demented snake up a steep hillside, others come in a spiral two hundred feet wide and circle into a boulder,” amateur wall historian Russell Swanson wrote in 1997. Over 12 years, he visited more than 40 miles of the stone structures. The walls seem out of place in California’s wild golden hills, evoking instead memories of tidy New England fields memorialized by poet Robert Frost, or the rich green pastures of Ireland.

Why, in such a vast landscape, didn’t builders simply use barbed wire? Or wood? Instead, they’re built of coarse-grained sandstone, abundant in these hills, called graywacke.

Native Americans say they historically had little interest in erecting boundaries. “In general, our ancestors did not believe in scarring or altering Mother Earth,” said Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. In 1904, John Fryer, a UC Berkeley professor of Oriental languages and literature, asserted that they were “undoubtedly the work of Mongolians. … The Chinese would naturally wall themselves in.”

Several years later, ethnologist Henry C. Meyers agreed they were the product of strong and ancient civilizations: “Neither man nor men of the present day could possibly put large stones of these walls in place without appliances of some kind.”

Dr. Robert F. Fisher, the founder of the Mission Peak Heritage Foundation, told the Santa Cruz Sentinel in 1984 that he was mystified: “They predate the Indians. They predate the Spaniards. It doesn’t fit in with any of the later histories.”

More recently, lichen analyses date the walls back to the 1850s to 1880s — the post-Gold Rush era, when California was swelling with newcomers anxious to lay their claim on acreage. While imperfect, the technique dates inanimate objects by measuring the diameter of growing lichens.

That evidence hasn’t stopped the internet from spawning its own theories, crediting mythical Lemurians — tall people who breathed through scaly aqua skin and sought refuge in California after the disappearance of the Pacific continent of Mu. Much more likely is an explanation put forth by a consensus of experts like Fentress; State Parks archaeologist Hylkema; and Beverly Ortiz, cultural services coordinator of the East Bay Regional Park District.

The walls were likely built to contain cattle by new European immigrants in the post-Gold Rush era, perhaps using unpaid or low-paid Native American, Chinese or Mexican labour, they believe. The stones stand as a legacy of our once-rural culture, poignant reminders of people long gone. Unlike the railroad or mining tycoons — the Crockers, Stanfords, Huntingtons and Floods — these early ranchers left no mansions, antiques or jewellery. Only rocks.

“The rock walls throughout the East Bay are neither ancient nor mysterious, even if the specific individuals who made them are unknown to us today,” Ortiz said. “They are associated with historic Euro-American ranching, dairy and dry farming activities.”

The historians note that cattle and sheep don’t need tall walls to be managed; they’re docile and don’t jump. The rocks, Fentress and Ortiz said, also could have been used to help catch or drain water or establish boundaries between ranches.

But which ethnic group built the walls?

The Portuguese were among the early ranchers, said Robert Burrill and Joseph Ehardt, of the Milpitas Historical Society. But other immigrants, such as Italians, Irish and Spaniards, may have brought wall-building skills from their homelands.

These post-Gold Rush settlers, who were not wealthy, likely built walls with their own hands, Fentress said. But they also may have enlisted low-cost labour from other ethnic groups, such as Mexicans — who had been displaced from their ranchos — and Chinese, who build the railroads and projects like Oakland’s Lake Chabot dam. Or perhaps they were built by Native Americans during an era that authorized the forced apprenticeship of native peoples, a practice not banned until the 1860s.

Archaeologists say the walls are a ghostly elegy of their builders.

“They are essentially the archaeology of the working class, the common people who came here and made a living,” Fentress said. “It is the only evidence we have of these people’s lives — and it is important to tell that story as well as we can.”