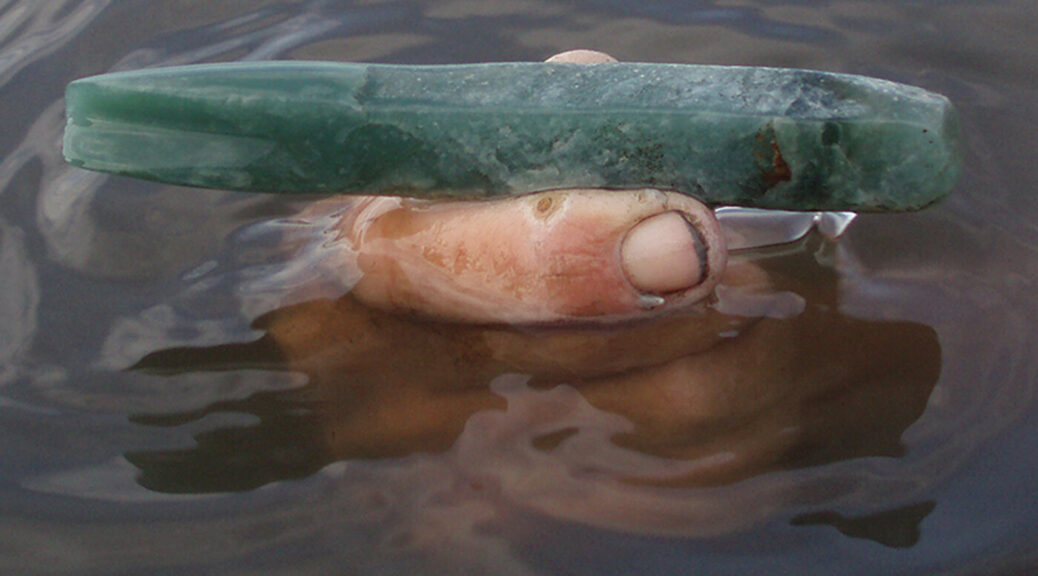

Jadeite tool discovered in ancient underwater salt works

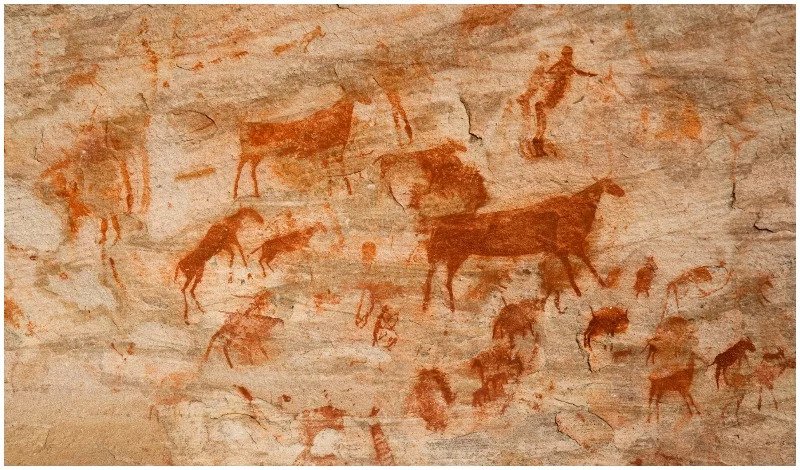

In the enigmatic culture of the Maya people, Jade took up a special place, crafted into elaborate trinkets rich with ancient meaning and lore.

But this precious stone was not meant for decorative or ornamental finery. Jade – in the form of its mineral variety, jadeite – also seems to have had its uses in the toil of manual labour, even among the grinding backdrop of long-ago salt works.

Such an unbelievably well-preserved jadeite gouge tool and its handle were discovered by scientists from the Louisiana State University on the grounds of what was once an ancient Mayan salt work in Belize.

This rare find – preserved among the underwater remains of a salt works called Ek Way Nal – represents the first time such a jadeite object has been discovered with its associated handle (in this case made from Honduras rosewood).

But the fact it was found at a salt works at all is both unexpected and noteworthy, the researchers say.

“High-quality translucent jadeite is normally associated with ritual or ceremonial contexts in the Maya area,” the researchers, led by archaeologist and anthropologist Heather McKillop, explain in a new paper.

“The Ek Way Nal tool is made of exceptionally high-quality jadeite, which is surprising given its utilitarian context.”

Ek Way Nal is one of 110 sites comprising the Paynes Creek Salt Works: the submerged remnants of an ancient salt industry in southern Belize, where salt was produced by evaporating brine in boiling pots over fires.

Dozens of thatched wooden kitchens made up the salt works, built during the Classic Maya period (300–900 CE), but later abandoned when sea level rise flooded the coastal lagoon region.

Producing salt wouldn’t have been easy work, which is why it seems strange that such a high-quality jadeite object was found here, the researchers say.

“During the Classic Period, the use of high-quality translucent jadeite was typically reserved for unique and elaborate jadeite plaques, figurines, and earplugs (earrings) for royalty and other elites,” the team explains.

“Highly crafted jadeite objects were destined for use in dynastic Maya ceremonies, as gifts to other leaders to solidify alliances, or as burial offerings to accompany dynastic and other elites.”

Or, it appears, sometimes rare and valuable jadeite was shaped into chisels, forming the glittering green blade of a salt worker’s tool. While the mineral might seem out of place in this steamy, briny context, McKillop says it shows how the ancient Maya salt trade was going places – until it was washed under the waves.

“The salt workers were successful entrepreneurs who were able to obtain high-quality tools for their craft through the production and distribution of a basic biological necessity: salt,” says McKillop.

“Salt was in demand for the Maya diet. We have discovered that it was also a storable form of wealth and an important preservative for fish and meat.”

While we can’t be sure how the jadeite gouge would have been used, the researchers say it was probably not used on very hard materials, like stone or wood, although an analysis of its worn appearance suggests it was employed as a working tool.

“The use of jadeite as a utilitarian tool in a salt works indicates that even exotic materials, which often require expertise to fashion into tools, were selected for their hardness,” the authors write.

“Although the gouge was probably not employed in working wood or hard materials, it may have been used in other activities at the salt works, such as scraping salt, cutting and scraping fish or meat, or cleaning calabash gourds.”

Not exactly glamorous pursuits then, but it makes for yet another ancient relic that can help us discover the world of the ancient Maya, and learn their story through the objects that once defined them.