Sixth Dynasty Official’s Tomb Discovered in Saqqara

A team of archaeologists in Egypt has discovered the 4,300-year-old tomb of a man named Mehtjetju, an official who claimed that he had access to “secret” royal documents.

“The dignitary bore the name Mehtjetju and was, among other things, an official with access to royal sealed — that is secret — documents,” according to the hieroglyphs on the tomb, Kamil Kuraszkiewicz, a professor at the University of Warsaw’s Faculty of Oriental Studies, said in a statement.

Mehtjetju’s tomb was found next to the Step Pyramid of Djoser, which was constructed about 4,700 years ago in Saqqara.

It’s no coincidence that Mehtjetju’s tomb is next to the Step Pyramid, the first pyramid built by the ancient Egyptians.

Djoser “was an important and revered king from the glorious past,” and officials sometimes wanted to be buried beside his pyramid, even centuries after Djoser died, Kuraszkiewicz told Live Science in an email.

Mehtjetju lived sometime during the reign of the first three pharaohs of the sixth dynasty: Teti (reign ca. 2323 B.C to 2291 B.C.), Userkare (reign ca. 2291 B.C. to 2289 B.C.) and Pepi I (reign ca. 2289 B.C. to 2255 B.C.).

Mehtjetju would have served one or more of those pharaohs. His other titles included “inspector of the royal estate” and he was also a priest of the mortuary cult of the pharaoh Teti, according to the statement.

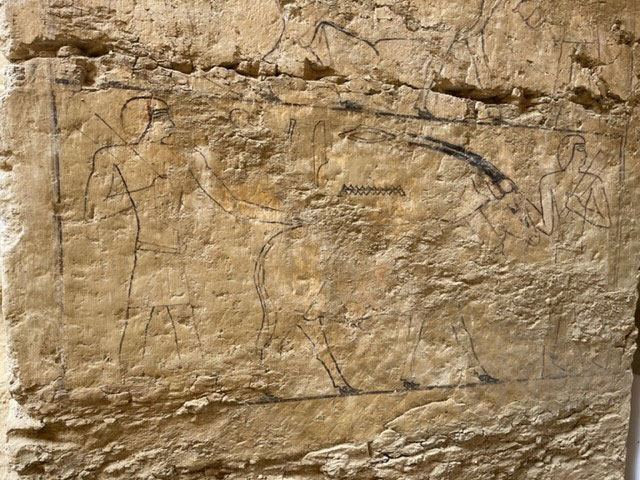

So far, archaeologists have excavated the façade (entrance) of the tomb’s chapel, finding hieroglyphic inscriptions, paintings and a relief depicting Mehtjetju. No family members are mentioned in the hieroglyphic inscriptions, but the burial chamber has not been excavated yet and the tomb seems to be part of a larger complex that may hold his family’s remains, Kuraszkiewicz told Live Science.

Mehtjetju’s high social status meant he could hire skilled artisans to build the tomb, according to the archaeologists, who said the façade’s reliefs were crafted by a skilled hand. However, some of the tomb’s rock is brittle and eroded, prompting conservators to intervene during the excavation.

Scholar reacts

Several details suggest it’s possible that the tomb’s decoration was not completed, Ann Macy Roth, a clinical professor of art history and Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University, who was not involved in the finding, told Live Science in an email.

Roth noted that one of the paintings shows the outlines of a man beside a large antelope known as an oryx. The fact that only the outline is shown “suggests that the decoration wasn’t completed,” Roth said, noting that this is an “interesting tomb” and she looks forward to hearing about future finds.

The discovery is “very exciting, as new tombs always are,” Roth said.

The team plans to resume excavations in September and hopes to uncover the burial chamber of the tomb at that time. The chamber may contain the mummy of Mehtjetju.