Bronze Age eating, social habits in the Balearic Islands documented in study

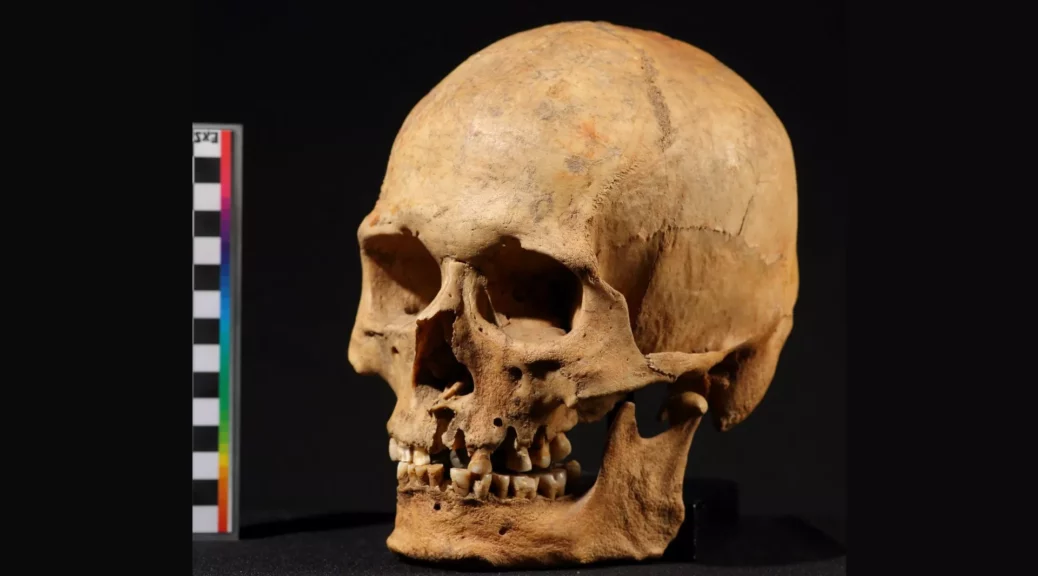

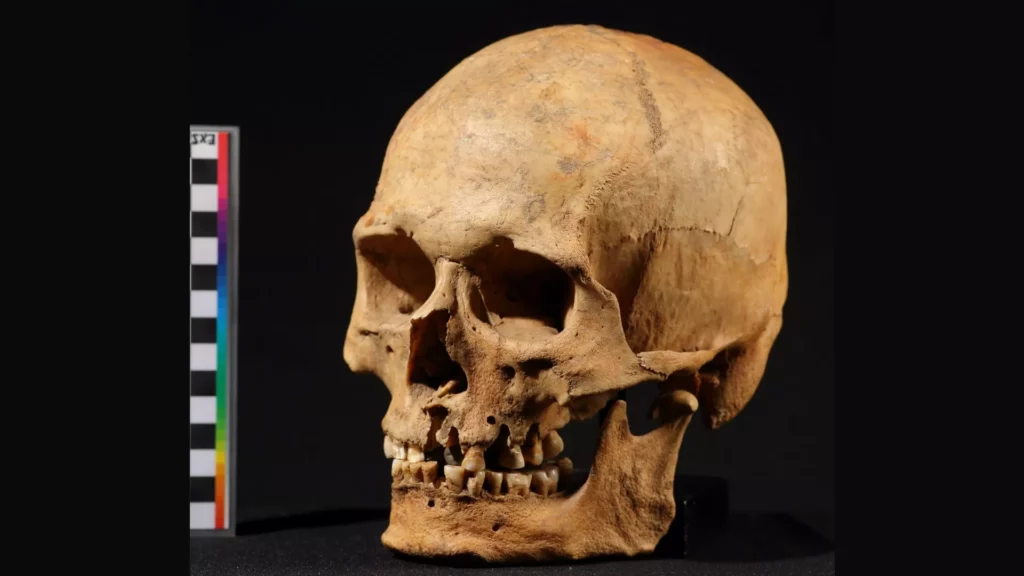

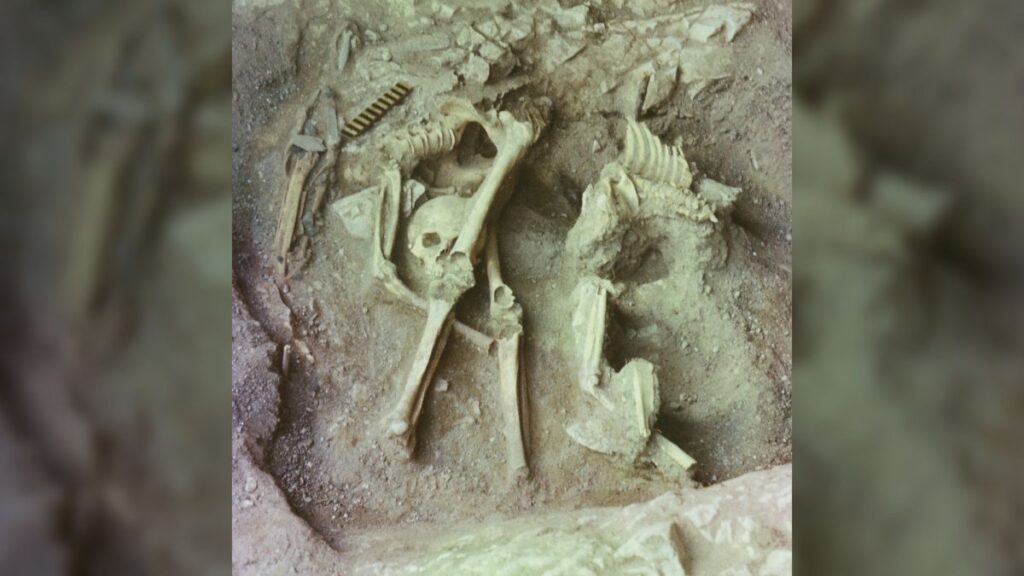

Researchers from a variety of Spanish institutions have managed to reconstruct the diet of some 50 individuals buried more than 3,000 years ago in the Cova des Pas’ necropolis in Menorca.

The study, coordinated by the UAB, indicates a diet of plants and meat, with all individuals having the same access to food, implying that they were a socially egalitarian group.

These findings form part of the study on eating habits of Bronze and Iron Age groups living in the Balearic Islands and contribute to the debate on the emergence and development of the first complex societies on the archipelago. This is the most complete study conducted to date of the paleodiet of ancient populations inhabiting the Balearic Islands.

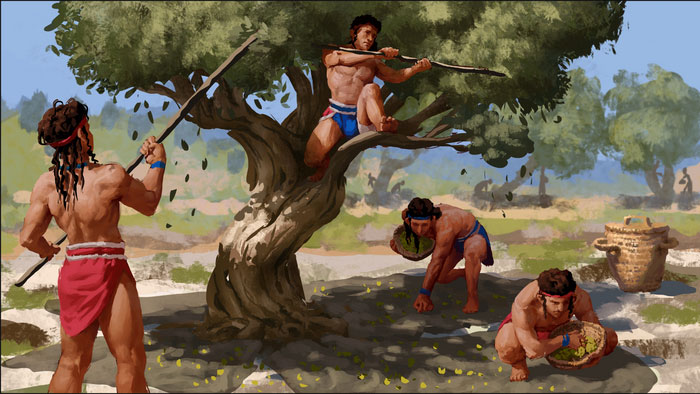

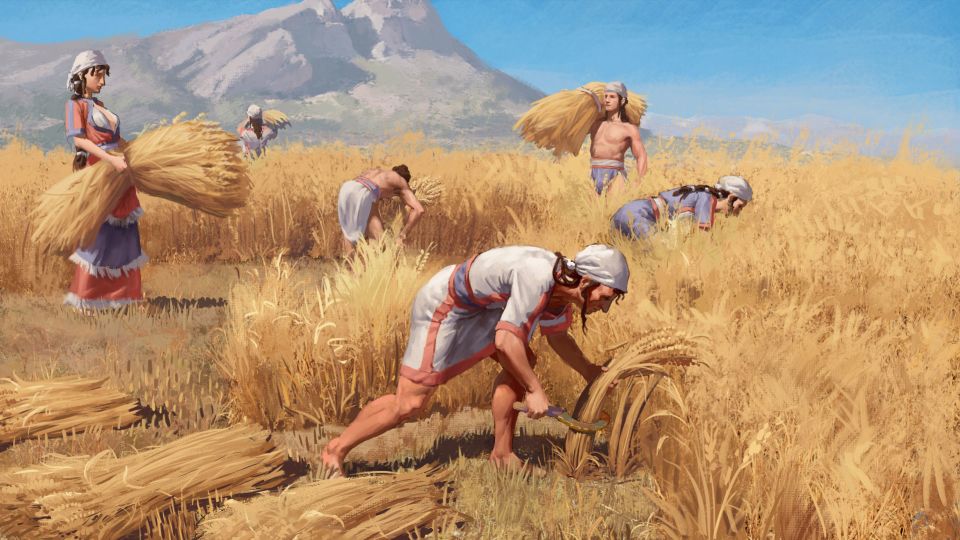

The individuals buried at the Cova des Pas site in Menorca between 3,600 and 2,800 years ago ate what the land had to offer, mainly plants, and also had a significant intake of animal protein.

This has been confirmed by a Spanish research team that has reconstructed the dietary pattern of 49 individuals buried in this collective tomb of the Talayotic culture, considered one of the largest and most exceptional prehistoric collections of human remains in the Balearic Islands.

The results also indicate that children were breastfed until they were about four years old and that all population groups had equal access to food, without distinctions by sex or age. The study was recently published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

The research was coordinated by UAB researchers Assumpció Malgosa and Carlos Tornero, who is also linked to the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA).

Pau Sureda, researcher at the Institute of Heritage Sciences (INCIPIT-CSIC), and Xavier Jordana, lecturer at the UAB and researcher at the Tissue Repair and Regeneration Laboratory of the University of Vic—Central University of Catalonia (UVic-UCC), as well as Filiana Sotiriadou, student of the UAB master’s degree in Biological Anthropology, also participated.

The study expands knowledge about the diet of the first Balearic population groups, a controversial subject of study. It confirms a mixed diet based on plants, with cereals such as wheat, and meat from goat and sheep herds, with little consumption of marine resources, and reinforces previous studies carried out at other Menorcan sites.

“Contrary to what has been seen in other settlements of the same period in Formentera or Mallorca, the consumption of marine food resources would have been occasional in these individuals,” says Carlos Tornero, Ramón y Cajal researcher in the UAB Department of Prehistory.

The research also contributes to the debate on the emergence and development of the first complex societies in the archipelago.

“These societies emerged and developed on the Balearic Islands during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, between 3,600 and 2,600 years ago, including the Naviform (present in all the islands) and Talayotic (only in Mallorca and Menorca) cultures,” explains Pau Sureda, researcher at INCIPIT-CSIC.

But the fact that all the population groups had the same access to food would indicate that these Menorcan groups were socially egalitarian, without the hierarchical organizations or population units differentiated by their social function or economic resources typical of more complex societies.

“Our results are consistent with previous studies of different Menorcan settlements and with paleodemographic and taphonomic studies carried out on individuals from the Cova des Pas, which found no differences in life expectancy or treatment of burials,” says Assumpció Malgosa, lecturer of Physical Anthropology at the UAB and director of the Biological Anthropology Research Group (GREAB-UAB).

The research was conducted using the combined analysis of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in samples of collagen from the skeletal remains of the individuals, which made it possible to identify the consumption of plant and animal foods from land and water, as well as in samples of faunal remains from the Son Mercer de Baix site, the closest site physically and temporally to the necropolis, to reconstruct the food chain and interpret the human data.