Head Wounds of Medieval Victim Analyzed

More than 700 years ago, a medieval “case of raw violence” ended a young man’s life with four sword blows to the head, according to a new study of the medieval “cold case.”

The brutality of the wounds suggests the murder may have been “a case of overkill,” study lead author Chiara Tesi, an anthropologist at the University of Insubria’s Center for Osteoarchaeology and Paleopathology in Italy, told Live Science. Tesi and her colleagues analyzed the victim’s skeletal remains with modern forensic techniques, including computed tomography (CT) — three-dimensional X-ray scans — and precision digital microscopy of the skull injuries.

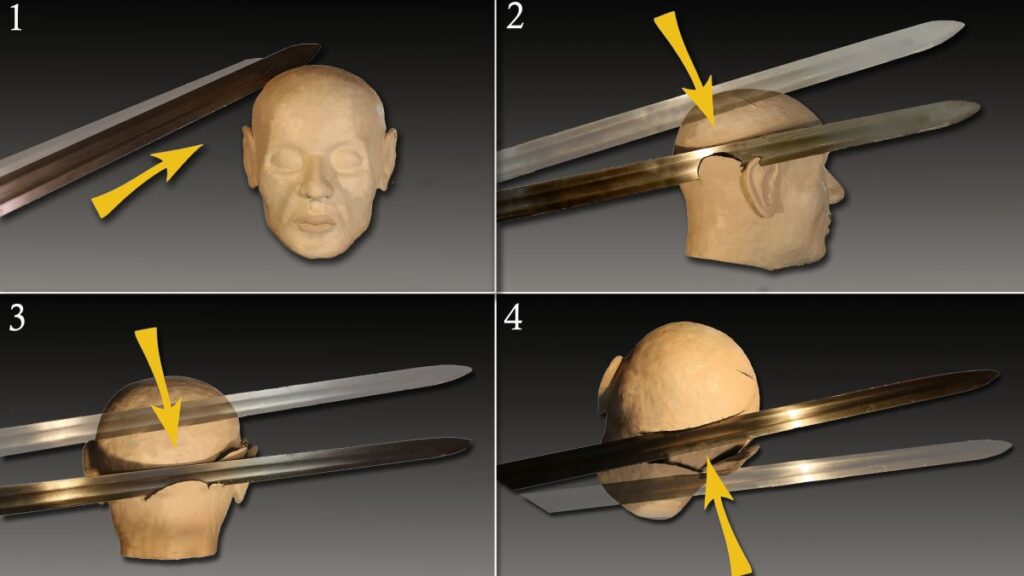

“The individual was probably taken by surprise by the attacker” and was unable to properly protect his head, she said in an email. After initially attacking the victim from the front, the murderer seems to have chased the man as he turned, likely trying to escape, as the deepest wounds were inflicted from behind, according to a study published in the December issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Brutal murder

Archaeologists discovered the victim’s skeleton in 2006 at the church of San Biagio in Cittiglio, a small town in Italy’s northern Varese province.

The oldest parts of the church are thought to date from the eighth century A.D., but the battered skeleton was found in a tomb in an atrium built near the entrance in the 11th century; radiocarbon dating indicates the victim was buried there before A.D. 1260.

The new study suggests the victim was a man who was between 19 and 24 years old when he was murdered. A study of the excavation published in 2008(opens in new tab) in the Fasti Online journal noted some of his injuries, but Tesi said the new study has revealed further injuries and the sequence of the murder.

She said the young man likely blocked or dodged the assailant’s initial attack, though the first blow still caused a shallow lesion on the top of the skull.

As he turned away to escape, however, “the victim was then hit in rapid succession by two other strikes, one affecting the auricle [ear] region and the other the nuchal [back of the neck] region,” she said. “At the end, probably exhausted and face down, he was finally hit by a last blow to the back of the head that caused immediate death.” This “evident overkill” suggested there may have been a complex motive for the murder, Tesi said; such a frenzied attack appeared to show the attacker was determined to finish his deadly job.

Medieval remains

The new study shows that the injuries were all caused by the same bladed weapon — probably a steel sword — while the position of the wounds suggest the injuries were inflicted by a single assailant, she said.

The researchers scoured historical records in an attempt to determine the victim’s identity, but “we didn’t find anything,” Tesi said.

His prominent burial, however, suggests he may have been a member of the powerful De Citillio family that had originally established the church.

A healed wound on the victim’s forehead suggests that he had experience in warfare; while features of his right shoulder blade were probably caused by “the habitual practice of archery and the use of a bow from an early age,” Tesi said — possibly a sign that he had often gone hunting for sport.

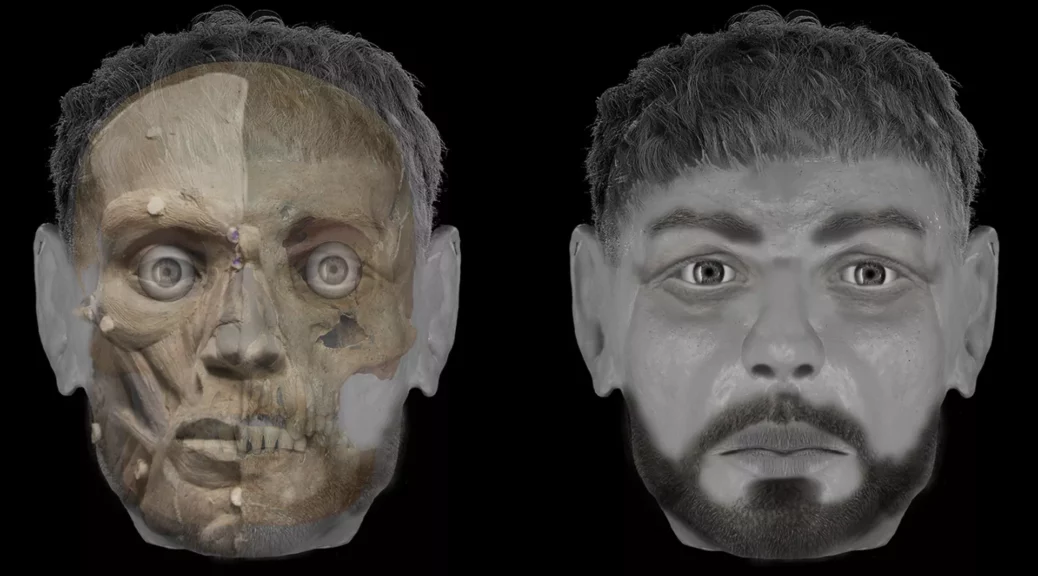

To examine how the sword blows impacted by the victim’s now-decomposed soft tissues, the researchers created a reconstruction of the victim’s face. “We tested wound formation by placing a blade on the reconstructed head and replicating the blows received by the subject,” she said.

The reconstruction helped assess the severity of the injuries.

“They’re using the head as a way of showing these multiple wounds to the skull,” Caroline Wilkinson(opens in new tab), the director of the Face Lab(opens in new tab) at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom, told Live Science. “It’s really interesting — a good use of forensic techniques to look at trauma to the head, and how those wounds have been caused.”

Wilkinson was not involved in the new study but has worked on reconstructing the faces of some of the victims of a medieval massacre of Jews in the English city of Norwich. Facial depictions “can create a personal narrative around human remains, rather than just looking at specimens in a glass box,” she said.

Tesi also believes that the reconstruction can help people relate to the victim.

“Seeing the face and eyes of a young man is definitely more emotional than simply looking at a skull,” she said.