A 3,300-Year-Old Bird Claw Was Discovered By Archaeologists While Digging In A Cave

Nearly three decades ago, a team of archaeologists were carrying out an expedition inside a large cave system on Mount Owen in New Zealand when they stumbled across a frightening and unusual object.

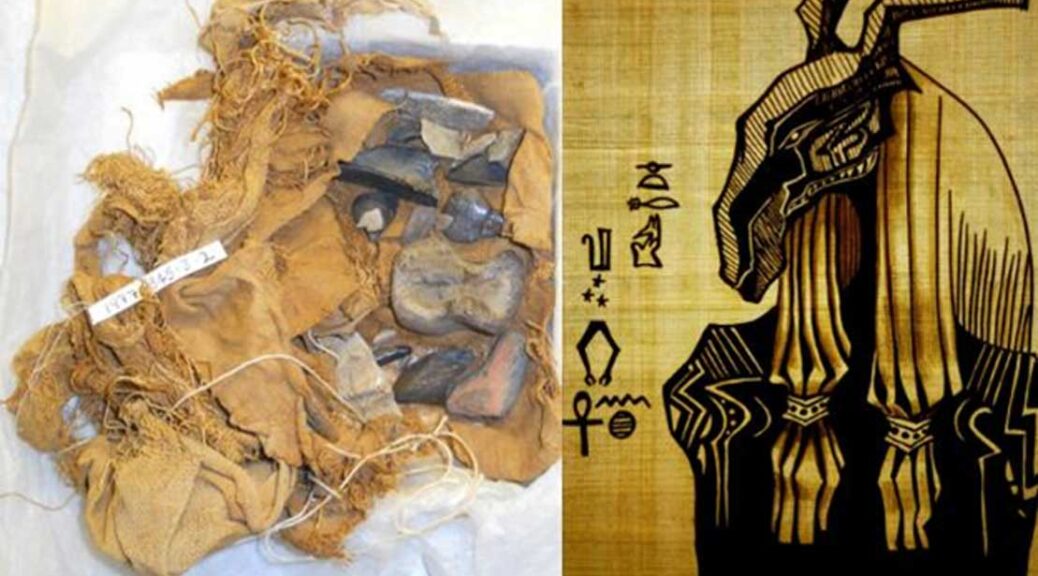

With little visibility in the dark cave, they wondered whether their eyes were deceiving them, as they could not fathom what lay before them—an enormous, dinosaur-like claw still intact with flesh and scaly skin.

The claw was so well-preserved that it appeared to have come from something that had only died very recently.

The archaeological team eagerly retrieved the claw and took it for analysis. The results were astounding; the mysterious claw was found to be the 3,300-year-old mummified remains of an upland moa, a large prehistoric bird that had disappeared from existence centuries earlier.

The upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) was a species of moa bird endemic to New Zealand. A DNA analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that the first moa appeared around 18.5 million years ago and there were at least ten species, but they were wiped from existence “in the most rapid, human-facilitated megafauna extinction documented to date.”

With some sub-species of moa reaching over 10 feet (3 meters) in height, the moa was once the largest species of bird on the planet. However, the upland moa, one of the smallest of the moa species, stood at no more than 4.2 feet (1.3 meters). It had feathers covering its whole body, except the beak and soles of its feet, and it had no wings or tail. As its name implies, the upland moa lived in the higher, more cooler parts of the country.

The Discovery of the Moa

The first discovery of the moa occurred in 1839 when John W. Harris, a flax trader and natural history enthusiast, was given an unusual fossilized bone by a member of an indigenous Māori tribe, who said he had found it on a river bank.

The bone was sent to Sir Richard Owen, who was working at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Owen was puzzled by the bone for four years—it did not fit with any other bone he had come across.

Eventually, Owen came to the conclusion that the bone belonged to a completely unknown giant bird. The scientific community ridiculed Owen’s theory, but he was later proved correct with the discoveries of numerous bone specimens, which allowed for the complete reconstruction of a moa skeleton.

Since the first discovery of moa bones, thousands more have been found, along with some remarkable mummified remains, such as the frightening-looking Mount Owen claw.

Some of these samples still exhibit soft tissue with muscle, skin, and even feathers. Most of the fossilized remains have been found in dunes, swamps, and caves, where birds may have entered to nest or to escape bad weather, preserved through desiccation when the bird died in a naturally dry site (for example, a cave with a constant dry breeze blowing through it).

The Rise and Fall of the Moa

When Polynesians first migrated to New Zealand in the middle of the 13th century, the moa population was flourishing. They were the dominant herbivores in New Zealand’s forest, shrubland, and subalpine ecosystems for thousands of years, and had only one predator—the Haast’s eagle. However, when the first humans arrived in New Zealand, the moa rapidly became endangered due to overhunting and habitat destruction.

“As they reached maturity so slowly, [they] would not have been able to reproduce quickly enough to maintain their populations, leaving them vulnerable to extinction,” writes the Natural History Museum, London.

“All moas were extinct by the time Europeans arrived in New Zealand in the 1760s.” The Haast’s Eagle, which relied on the moa for food, died out soon after.

Revival of the Moa?

The moa has frequently been mentioned as a candidate for revival through cloning since numerous well-preserved remains exist from which DNA could be extracted. Furthermore, since it only became extinct several centuries ago, many of the plants that made up the moa’s food supply would still be in existence.

Japanese geneticist Ankoh Yasuyuki Shirota has already carried out preliminary work toward these ends by extracting DNA from moa remains, which he plans to introduce into chicken embryos. Interest in the ancient bird’s resurrection gained further support in the middle of this year when Trevor Mallard, a Member of Parliament in New Zealand, suggested that reviving the moa over the next 50 years was a viable idea.