“Truly Heartbreaking”: Osage Nation Decries Sale of Cave Containing Native American Art

An anonymous bidder has purchased Picture Cave, a Missouri cave system filled with 1,000-year-old Native American artwork, for $2.2 million. Held by St. Louis–based Selkirk Auctioneers & Appraisers, the sale went forward despite the Osage Nation’s efforts to block it, reports Jim Salter for the Associated Press (AP).

In a statement quoted by the AP, the Osage Nation—which had hoped to “protect and preserve” the site—described the auction as “truly heartbreaking.”

“Our ancestors lived in this area for 1,300 years,” the statement reads. “This was our land. We have hundreds of thousands of our ancestors buried throughout Missouri and Illinois, including Picture Cave.”

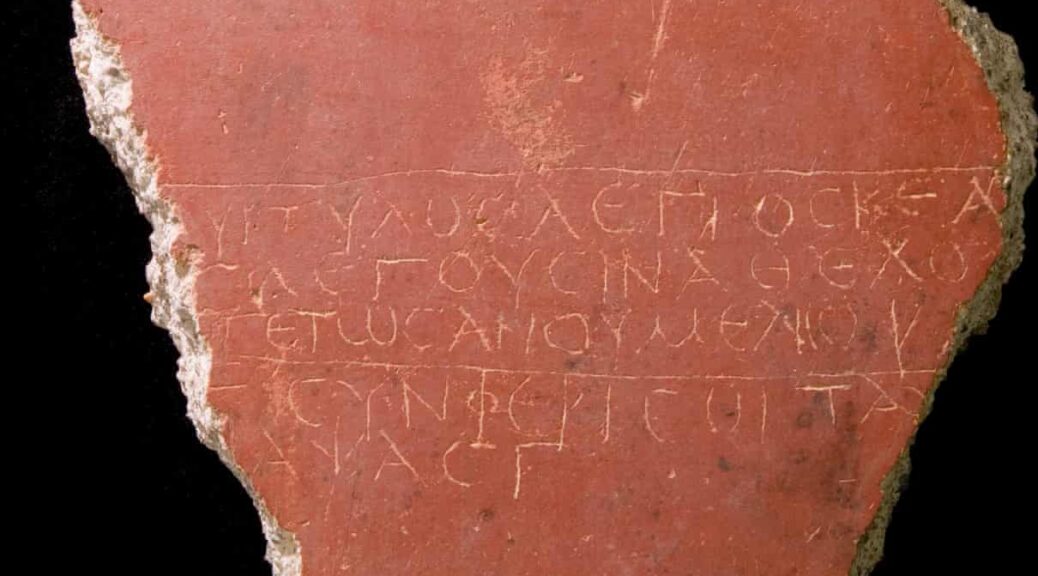

Selkirk’s website describes the two-cave system, located about 60 miles west of St. Louis, as the “most important rock art site in North America.” Between 800 and 1100 C.E., the auction house adds, people, used the caves for sacred rituals, astronomical studies and the transmission of oral tradition.

“It was a collective commune of a very significant space and there is only speculation on the number of Indigenous peoples that used the space for many, many, many different reasons, mostly communication,” Selkirk Executive Director Bryan Laughlin tells Fox 2 Now’s Monica Ryan.

Husband-and-wife scholarly team Carol Diaz-Granados and James Duncan, who have spent 20 years researching the cave, opposed the sale. Diaz-Granados is an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, while Duncan is the former director of the Missouri State Museum and a scholar of Osage oral history.

“Auctioning off a sacred American Indian site truly sends the wrong message,” Diaz-Granados tells the AP. “It’s like auctioning off the Sistine Chapel.”

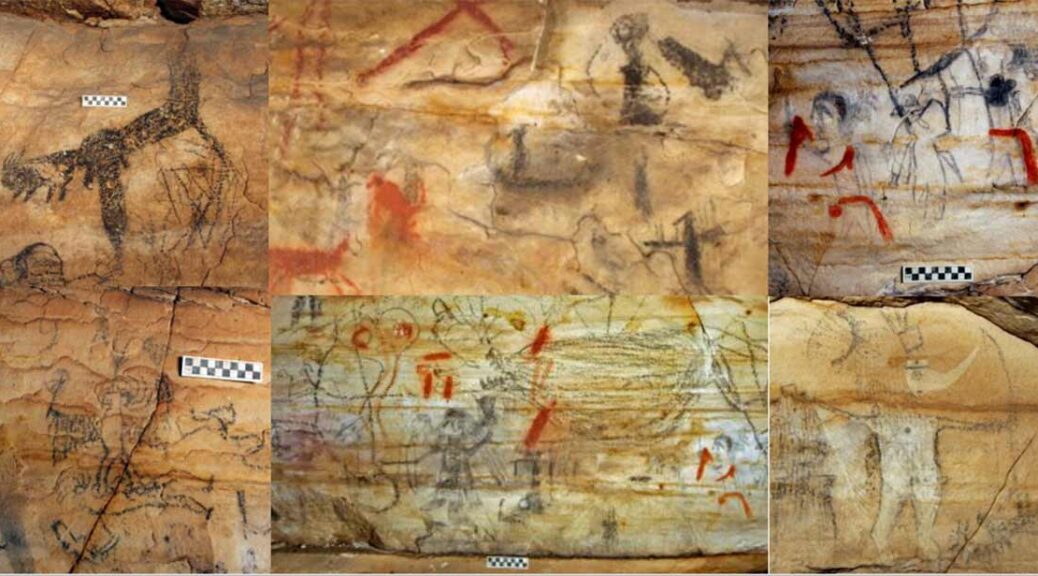

The scholar adds that the cave’s art, made largely with charred botanical materials, is more intricate than many other examples of ancient artwork.

“[Y]ou get actual clothing details, headdress details, feathers, weapons,” she says. “It’s truly amazing.”

Diaz-Granados tells St. Louis Public Radio’s Sarah Fenske that state archaeologists who first visited the cave decades ago thought the pictures were modern graffiti because of their high level of detail. But a chemical analysis showed that they dated back about 1,000 years. Duncan adds that the drawings hold clear cultural significance.

“The artists who put them on the wall did it with a great deal of ritual, and I’m sure there were prayers, singing—and these images are alive,” he says. “And the interesting thing about them as far as artists are concerned is the tremendous amount of detail and the quality of portraiture of the faces. Most of them are people—humans—but they’re not of this world; they’re supernatural.”

The artwork may represent an early achievement of the Mississippian culture, which spread across much of what’s now the southeastern and midwestern United States between about 800 and 1600 C.E., writes Kaitlyn Alanis for the Kansas City Star.

During this period, people in the region increasingly based their economies on the cultivation of corn and other crops, leading to the creation of large towns typically surrounded by smaller villages.

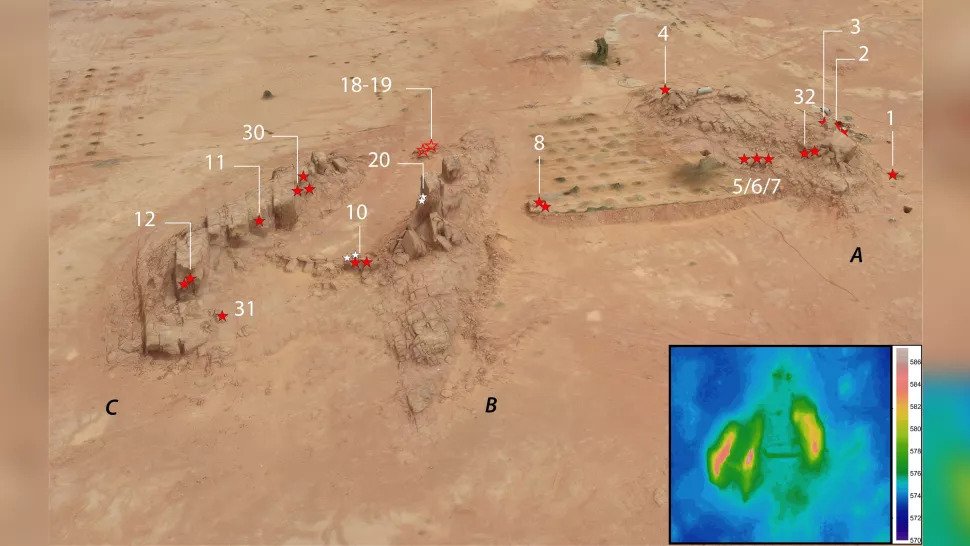

Per Encyclopedia Britannica, Mississippian people adopted town plans centred on a plaza containing a temple and pyramidal or oval earth mounds. These designs were similar to patterns adopted more than 1,000 years prior in parts of Mexico and Guatemala.

Among the most prominent surviving Mississippian sites are the Cahokia Mounds earthworks, which are situated just outside of St. Louis in Illinois. The city flourished from 950 to 1350 C.E. and was home to as many as 20,000 residents at its height. In 2008, Duncan told the Columbia Missourian’s Michael Gibney that the Picture Cave artists probably had ties to Cahokia. He argued that some of the drawings depict supernatural figures, including the hero known as Birdman or Morning Star, who was known to have been important in Mississippian culture.

The cave system and 43 acres of surrounding land were sold by a St. Louis family that had owned them since 1953. The sellers mainly used the land for hunting. In addition to its cultural significance, the cave system is home to endangered Indiana bats.

Laughlin tells the AP that the auction house vetted potential buyers. He believes the new owner will continue to protect the site, pointing out that, as a human burial site, the location is protected under state law. It’s also fairly inaccessible to would-be intruders.

“You can’t take a vehicle and just drive up to the cave,” Laughlin says. “You have to actually trek through the woods to higher ground.” Only then can visitors squeeze through the 3- by 3-foot cave opening.