Mass grave of 25 Christian soldiers who were ”decapitated” during a 13th century Crusade is unearthed in Lebanon

A pair of mass graves containing 25 Crusaders who were slaughtered during a 13th-century war in the Holy Land have been unearthed in Lebanon. A team of international archaeologists uncovered the gruesome scene at Sidon Castle on the eastern Mediterranean coast of south Lebanon.

Wounds on the remains suggest the soldiers died at the end of swords, maces and arrows, and charring on some bones means they were burned after being dropped into the pit. Other remains show markings on the neck, which likely means these individuals were captured on the battlefield and later decapitated.

Historical records written by crusaders show that Sidon was attacked and destroyed in 1253 by Mamluk troops, and again in 1260 by Mongols, and the soldiers found in the mass graves likely perished in one of these battles.

The Crusades were a series of religious wars fought between 1095 and 1291, in which Christian invaders tried to claim the near East, including Lebanon where the 25 dead soldiers were found.

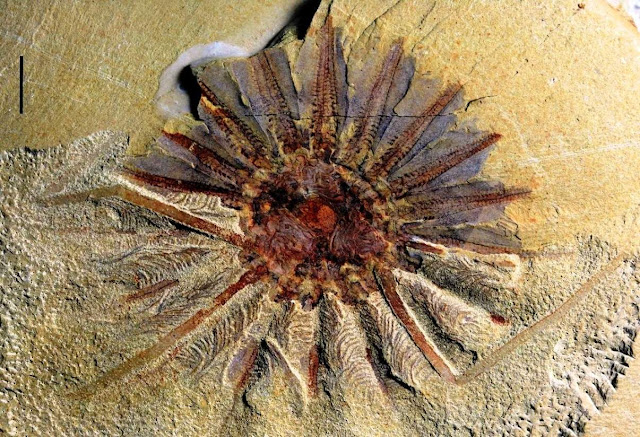

The mass graves were found within the town walls and were rectilinear grave pits that also contained artefacts that belonged to the Crusaders.

‘Within the grave pit (burial 110) a wide variety of artefacts were observed dispersed amongst the human and non-human bones, with no immediate patterning evident, reads the study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

‘Metal finds included copper alloy buckles and fittings, at least two different sizes of iron nails, other iron fittings, a silver coin, a silver finger-ring and a single copper alloy arrowhead.

Other finds included medieval potsherds, residual Persian period potsherds, glass fragments, and a small piece of charred, twisted fibre.’

Archaeologists knew the remains belonged to Crusaders after discovering the European style belt buckles and a crusader coin within the graves.

DNA and isotope analyses of their teeth further confirmed that some of the men were born in Europe, while others were the offspring of crusader settlers who migrated to the ‘Holy Land’ and intermarried with local people.

The team ventured into the grave pits to take a closer look at the pile of bones that showed many of the soldiers were attacked from behind as they were running away from the battle. Others have sword wounds across the back of the neck, indicating they were possibly captives executed by decapitation after the battle.

Dr Richard Mikulski of Bournemouth University, who excavated and analyzed the skeletal remains and worked with the archaeologists at the Sidon excavation site, explained, ‘All the bodies were of teenage or adult males, indicating that they were combatants who fought in the battle when Sidon was attacked.

‘When we found so many weapon injuries on the bones as we excavated them, I knew we had made a special discovery.’

Bournemouth University colleague Dr Martin Smith, said in a statement: ‘To distinguish so many mixed up bodies and body parts took a huge amount of work, but we were finally able to separate them out and look at the pattern of wounds they had sustained.’

‘The way the body parts were positioned suggests they had been left to decompose on the surface before being dropped into a pit sometime later. Charring on some bones suggests they used fire to burn some of the bodies.’

Dr Piers Mitchell of the University of Cambridge, who was the crusader expert on the project, explained: ‘Crusader records tell us that King Louis IX of France was on crusade in the Holy Land at the time of the attack on Sidon in 1253.

‘He went to the city after the battle and personally helped to bury the rotting corpses in mass graves such as these. Wouldn’t it be amazing if King Louis himself had helped to bury these bodies?’