Cryptic 2,700-year-old pig skeleton found in Jerusalem’s City of David

Israeli archaeologists have unearthed the complete skeleton of a piglet in a place and time where you wouldn’t expect to find pork remains: a Jerusalem home dating to the First Temple period.

The 2,700-year-old porcine remains were found crushed by large pottery vessels and a collapsed walls during excavations in the so-called City of David, the original nucleus of ancient Jerusalem. The team of archaeologists behind the discovery reported their find in a study published in the June edition of the journal Near Eastern Archaeology.

The find of swine adds to previous research showing that pork was occasionally on the menu for the ancient Israelites and that biblical taboos on this and other prohibited foods only came to be observed centuries later, in the Second Temple period. It also ties into broader questions about when the Bible was written and when Judaism as we know it was born.

This little piggy wasn’t bacon

The animal’s skull clearly identifies it as a domestic pig, as opposed to a wild swine, and its presence indicates that pigs were raised for food in the capital of the ancient Kingdom of Judah, says Lidar Sapir-Hen, an archaeozoologist at Tel Aviv University and at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.

The fact that the skeleton was found intact suggests that this specific piglet, less than seven months old, was not eaten, but died accidentally when the building was destroyed at some point in the eighth-century B.C.E, Sapir-Hen and colleagues report.

But there can be little doubt of what the piglet’s ultimate fate would have been having its home not collapsed for as yet unclear reasons. In addition to large storage jars and smaller cooking vessels, the room where the pig was unearthed also hosted dozens of animal bones from sheep, goats, cattle, gazelles, as well as fish and birds, the archaeologists report.

Most of these remains were burnt or showed signs of butchery, meaning the animals had long been dead and eaten when the building was destroyed, Sapir-Hen says.

This suggests that this room was where meals were prepared or eaten,” she says. “So this pig was just waiting for its turn.”

We don’t know the cause of the building’s collapse, as there is no known major destruction event in Jerusalem in the eighth century B.C.E., says Joe Uziel, the Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist who led the dig. It may have been destroyed by an earthquake or a more localized event, he speculates.

In any case, the structure was rebuilt and continued to be in use until around 586 B.C.E., when the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the First Temple, Uziel says. The building had at least four rooms and was located in a fairly central area near the Gihon spring, the main source of water for the city at the time. Constructed with rough fieldstones, it was probably a private home, although the fact that bullae, or seal impressions, were unearthed in another room suggests it may have also had an additional, administrative function, Uziel says.

The excavation also yielded an elegantly carved bone pendant and a human figurine. Together with the great variety of animals found alongside the pig, all of this indicates the house was occupied by an upper-class family, the archaeologist says.

The importance and central location of the house suggest that pig husbandry and pork consumption may have been a rare treat, but still very much part of “mainstream” food habits, he says. In other words, it doesn’t look like this was something done secretively by, say, a poorer household that may have been desperately in need of a quick meal.

At this point, we have to wonder how to square the idea that pigs were infrequently but openly raised in Jerusalem with the biblical injunction that: “The swine, though he divides the hoof, and be cloven-footed, yet he cheweth not the cud; he is unclean to you. Of their flesh shall ye not eat, and their carcase shall ye not touch; they are unclean to you.” (Leviticus 11:7-8

It’s the Levantine economy, stupid

While domesticated pig bones are rarely found in Jerusalem and in most of the Levant, they are not entirely absent, Sapir-Hen notes. In excavations from the First Temple period in Jerusalem and in other sites from the Kingdom of Judah, swine bones constitute up to 2 per cent of the animal remains unearthed, she says.

Already back in the 1990s, archaeologists also observed that pig bones were much more frequent in the coastal strip that was inhabited by the Philistines. Scholars thus concluded that a dearth of pig bones identified a site as Israelite and that the biblical ban on partaking in pork was already known and observed in the First Temple period.

But more recent research by Sapir-Hen and others has shown that the picture is much more complex. For one thing, the near absence of pig bones is not unique to Israelite sites of the Iron Age, the period that roughly corresponds to the First Temple era. Swine is equally scarce in most of Canaan during the preceding era, the Late Bronze Age, a time before the writing of the Bible or the formation of ancient Israel.

This dearth then continues in the Iron Age, not only in Judah but in many of its neighbours, including sites linked to the Canaanites, Phoenicians and Arameans, Sapir-Hen notes. Even when it comes to the supposedly pork-loving Philistines, the situation is actually more nuanced.

While the diet of Philistine city-dwellers did include a larger proportion of pigs, which were seemingly imported from Greece, swine bones are almost absent from their rural settlements, in keeping with the dietary habits of the rest of the Levant. Equally puzzling is the fact that in the Kingdom of Israel, Judah’s northern neighbour, a pig is rare in the early Iron Age, but it increases to up to 8 per cent of the animal mix at urban sites in the eighth century B.C.E.

All of this indicates that the tendency to eschew pork in the Iron Age cannot be linked to a specific ethnic identity or to the biblical prohibition, Sapir-Hen concludes. Pigs were only a small part of the Levantine diet most probably because other animals, especially goats, sheep and cattle, were more suited to the local environment and economy.

Pigs can be raised in an urban environment, as they require less space, but they also need a nearby water source: it is perhaps not a coincidence that the Jerusalem piglet was found near the city’s spring. This may explain why, throughout the Levant, swine occurrences only tend to rise at times and in places where populations increase and are concentrated in larger urban settlements, whether in Philistia, in the Kingdom of Israel or, to a lesser extent, in the more built-up sections of Judah’s capital, Jerusalem.

Gods, figurines and shrimp

This also gels with a growing body of research on the Israelite religion in the First Temple period. While scholars believe that parts of the Bible were already compiled at the tail end of this era, it is generally agreed that the holy text we know today only reached its final form after the Babylonian exile, in the Second Temple period.

Whenever the Bible was actually written, archaeological finds have shown that, in practice, First Temple-period Judaism was very different from the religion it would later become. While the ancient Israelites believed in Yahweh, the God of the Bible, they also worshipped other deities, including Asherah, who was thought to be God’s wife. They liberally made figurines and other graven images, ostensibly banned by the Second Commandment.

ARTICLE YOU MAY LIKE

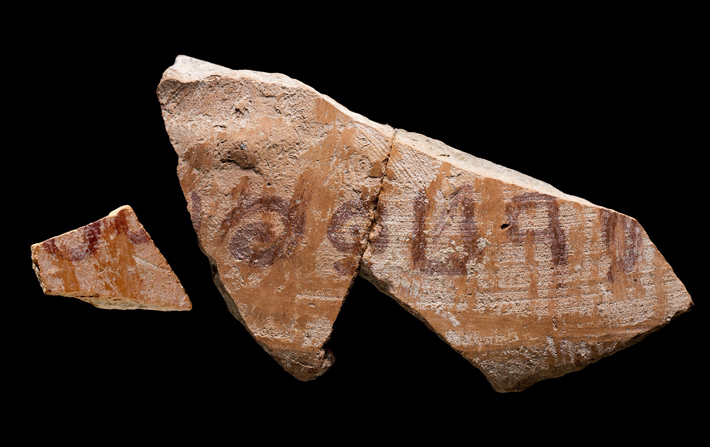

3,000-YEAR-OLD INSCRIPTION FOUND IN ISRAEL

NEW EARLY HUMAN DISCOVERED IN 130,000-YEAR-OLD FOSSILS AT ISRAELI CEMENT SITE

Additionally, a study published just last month in the Tel Aviv journal of archaeology looked at the finding, at archaeological sites throughout Israel, of bones from scaleless and finless fish, which are also prohibited by the Bible’s dietary rules. The research showed that catfish, sharks and other non-kosher fish were commonly consumed in Jerusalem and Judah during the First Temple period, and only for the late Second Temple period is there clear evidence that Jews were eschewing such banned seafood.

In other words, biblical prohibitions that are considered signposts of the Jewish faith today were unknown, unheeded or non-existent back in the First Temple period. And it seems that, from time to time, the ancient Israelites were not averse to literally bringing home the bacon.