A 12,500-year-old sphinx discovered in Pakistan

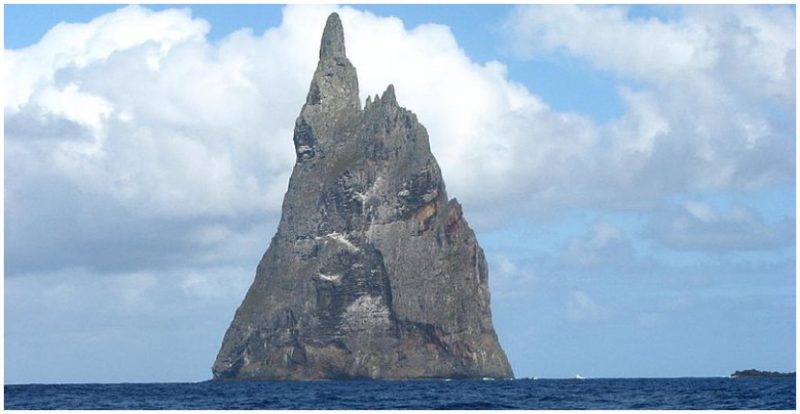

The Balochistan Sphinx, or the Lion of Balochistan, is a rare shape in modern-day Pakistan. The oddly-shaped building, which is located in Lesbela, Pakistan, resembles the famous ancient Egyptian Sphinx in Giza in some details.

As a response, modern historians and writers believe that long-lost cultures flourished before ancient civilizations such as the Egyptians, hence this odd Pakistani formation has, therefore, been the subject of debate and discussion.

The odd geological formation in Pakistan was only revealed to the world when, in 2004, the Makran Coastal Highway opened up, and people started transiting near the geological formation. The highway linked Karachi with the port town of Gwadar on the Makran coast.

Despite a complete archaeological survey, the odd Pakistani “Sphinx” is often passed off by experts as a natural formation. Different images from different angles of the geological formation may suggest a certain resemblance to the more famous Egyptian Sphinx; a monument thought to have been carved out of a single, massive limestone block, sometime around 4,500 years ago, during the reign of Khafre, the man who is also credited with building the second-largest pyramid at the Giza plateau.

Photographs of the Balochistan Sphinx—located in the Hingol National Park—cause more confusion than clarity, and some people may find it hard to believe that such a geological formation was indeed carved and shaped by natural forces. For some, the location where the oddly-shaped formation stands may seem as if it were carved sometime in the distant past.

A glance at the “Sphinx” appears to show a well-defined jawline, as well as clearly noticeable facial features such as eyes, mouth, and nose. These also seem to be perfectly spaced, as if carved in perfect proportion to one another.

So, wouldn’t this suffice to say that the Balochistan Sphinx was carved by man and not my nature? Not really. We could be seeing something that resembles the Sphinx of Egypt because of Pareidolia, a psychological phenomenon that causes us to see things that aren’t there.

Also, it is impossible to clearly state that something is or is not a monument, or carved by man, by simply looking at what appears to be a rock formation in the middle of nowhere.

Without a proper archaeological survey, we can’t possibly know whether the oddly shaped geological formation was carved by weather erosion or by ancient civilizations.

Throughout the years, different opinions defined the odd formation as one of a natural origin, and one of artificial origin. The opinions are divided.

One author, Bibhu Dev Misra, who runs this blog, argues the Balochistan Sphinx is part of a massive architectural complex, and that the Sphinx is clearly surrounded by the remnants of ancient temples carved into the bedrock.

Describing the Sphinx Bibhu Dev Misra explains that: A cursory glance at the impressive sculpture shows the Sphinx to have a well-defined jawline, and clearly discernible facial features such as eyes, nose, and mouth, which are placed in seemingly perfect proportion to each other.

But if it really is a manmade monument, who carved it and when was it carved?

Oddly enough, just as the ancient Egyptian Sphinx appears to have a headdress—called a Nemes—the Pakistani counterpart seems to have one as well. Of course, this may be just part of pareidolia kicking in, drawing dots between a well-known monument—the ancient Egyptian Sphinx—and a geological formation that resembles the Egyptian monument.

In addition to certain elements around the upper part of the geological formation bearing a resemblance to the Egyptian Sphinx, Bibhu Dev Misra argues that more symmetrical features near the alleged Sphinx are evidence of human activity, and contradict the notion that the site was carved by weather erosion.

The author argues that we can see a clear symmetrical formation of steps and pillars around the Sphinx, which offer further evidence to the idea that the Balochistan Sphinx was carved by man and not by nature.

“The steps appear to be evenly spaced, and of uniform height. The entire site gives the impression of a grand, rock-cut, architectural complex,” the researcher writes.

As for its age, it impossible to know. The age of 12,000 years has been thrown around by various blogs and authors. However, since we can’t know whether this is really Sphinx or not, it is impossible to suggest an age for the alleged Sphinx.

Without extensive archaeological fieldwork and archaeological excavations, we can’t possibly know whether the site of the Balochistan Sphinx was carved by a long-lost, forgotten civilization—as some authors think—or if it is just another site on Earth where weather erosion and geology carved a curious formation.