10,000 Roman coins unearthed by amateur metal detector enthusiast

An amateur metal detector enthusiast discovered a massive train with more than 10.000 Roman coins on his first ever treasure hunt.

The silver and bronze ‘nummi’ coins, dating from between 240AD and 320AD, were discovered in a farmer’s field near Shrewsbury, in Shropshire.

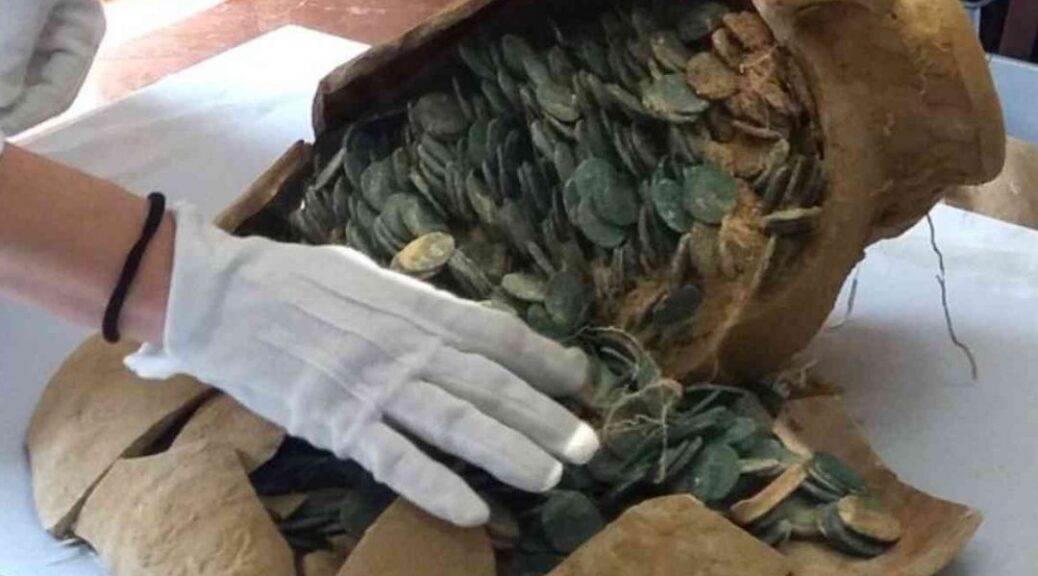

Finder Nick Davies, 30, was on his first treasure hunt when he discovered the coins, mostly crammed inside a buried 70lb clay pot. Experts say the coins have spent an estimated 1,700 years underground.

The stunning collection of coins, most of which were found inside the broken brown pot, was uncovered by Nick during a search of land in the Shrewsbury area – just a month after he took up the hobby of metal detecting.

His amazing find is one of the largest collections of Roman coins ever discovered in Shropshire. And the haul could be put on display at Shrewsbury’s new £10million heritage center, it was revealed today.

It is also the biggest collection of Roman coins to be found in Britain this year. Nick, from Ford, Shropshire, said he never expected to find anything on his first treasure hunt – especially anything of any value. He recalled the discovery and described it as ‘fantastically exciting’.

Nick said: ‘The top of the pot had been broken in the ground and a large number of the coins spread in the area. All of these were recovered during the excavation with the help of a metal detector.

‘This added at least another 300 coins to the total – it’s fantastically exciting. I never expected to find such treasure on my first outing with the detector.’

The coins have now been sent to the British Museum for detailed examination before a report is sent to the coroner. Experts are expected to spend several months cleaning and separating the coins, which have fused together.

They will also give them further identification before sending them to the coroner. A treasure trove inquest is then expected to take place next year. Peter Reavill, finds liaison officer from the Portable Antiquities Scheme, records archaeological finds made by the public in England and Wales.

He said the coins were probably payment to a farmer or community at the end of a harvest. Speaking to the Shropshire Star, Mr. Reavill said the coins appear to date from the period 320AD to 340AD, late in the reign of Constantine I.

He said: ‘The coins date to the reign of Constantine I when Britain was being used to produce food for the Roman Empire.

‘It is possible these coins were paid to a farmer who buried them and used them as a kind of piggy-bank.’

Mr. Reavill said that among the coins were issues celebrating the anniversary of the founding of Rome and Constantinople. In total, the coins and the pot weigh more than 70lb.

He added: ‘This is probably one of the largest coin hoards ever discovered in Shropshire.

‘The finder, Nick Davies, bought his first metal detector a month ago and this is his first find made with it. The coins were placed in a very large storage jar which had been buried in the ground about 1,700 years ago.’

However, Mr. Reavill declined to put a figure on either the value of the coins or the pot until the findings of the inquest are known, but he described the discovery as a ‘large and important’ find.

Mr. Reavill said the exact location of the find could not be revealed for security reasons.