Spider-Like Creature With a Tail Was Just Found in 100 Million-Year-Old Amber

Amber mined for centuries in Myanmar for jewelry is a treasure trove for understanding the evolution of spiders and their other arachnid relatives.

This week, two independent teams describe four 100-million-year-old specimens encased in amber that look like a cross between a spider and a scorpion.

The discovery, “could help close major gaps in our understanding of spider evolution,” says Prashant Sharma, an evolutionary developmental biologist at the University of Wisconsin in Madison who was not involved in the work.

Arachnids are a group of eight-legged invertebrates that includes scorpions, ticks, and spiders. Spiders, which crawled into existence some 300 million years ago, are known for their spinnerets—modified “legs” that produce silk and control its extrusion from tiny pores called spigots.

Male spiders have also evolved another modified “leg” between their fangs and the back four pairs of legs that inserts sperm into the female.

All but the most primitive spiders have smooth backs, unlike the segmented abdomens of scorpions, which are believed to have diverged from an ancestral arachnid more than 430 million years ago.

But in 1989, researchers discovered a suspicious, spigot-bearing fossil that was 100 million years older than the earliest known spider.

By 2008, paleobiologists realized that this ancient silk producer was just a spider relative, perhaps a stepping stone to true spiders.

Researchers put it into the group Uraraneida, which was thought to have thrived between 400 million and 250 million years ago. That left unanswered many questions about when spinnerets and other spider traits first evolved.

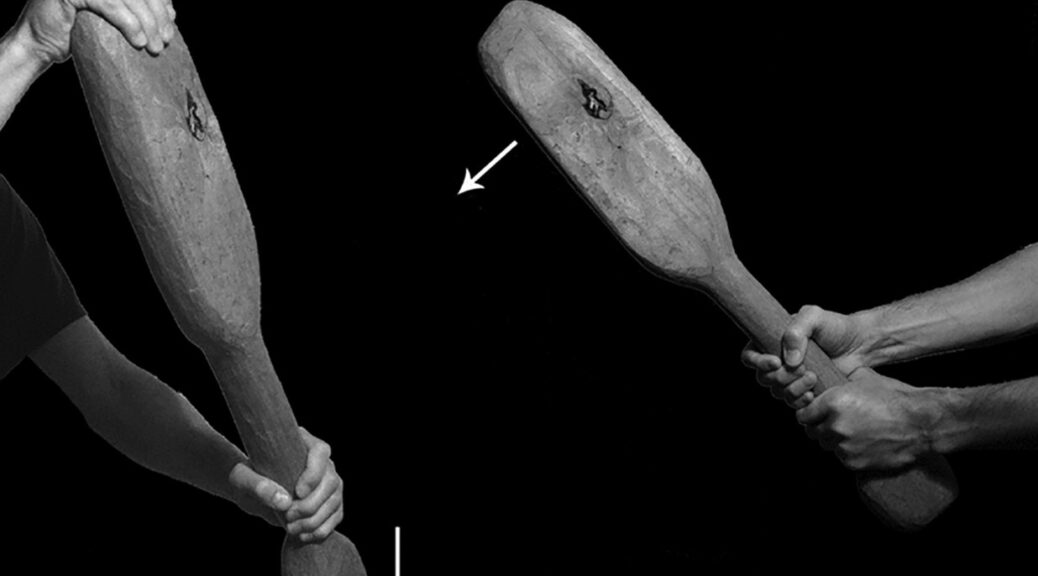

Then, several years ago, amber fossil dealers independently approached two paleobiologists at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology in China with what looked like 5-millimeter-long Uraraneida encased in amber.

One of them, Wang Bo, pulled together a team to look at his two specimens, which they eventually named Chimerachne yingi (“chimera spider” in Latin). The other paleobiologist, Huang Diying, assembled a second team that examined a different pair of these fossils.

The two groups say they didn’t know about each other until after they submitted their results to the same journal. But, despite some differences, “they draw the same conclusion—that fossil uraraneids, as this group is called, are the closest extinct relatives of spiders,” says Greg Edgecombe, a paleobiologist at the Natural History Museum in London, who was not involved with the work.

One group’s specimens give a really clear view of the top of this organism and the other, a great look at the underside, spinnerets and all, Huang and his colleagues report today in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

“The degree of preservation is exquisite, and the fossils’ anatomy is easy to interpret,” Sharma says. The presence of the spinnerets, he adds, means they must have originated “very early” in arachnid evolution. The male specimens also have the special appendages for inserting sperm into the female.

Yet they also have a segmented abdomen and a long tail, like a whip scorpion’s whip, Wang and his colleagues report today in the same journal. “These things appear to be essentially spiders with tails!” says Jason Bond, an evolutionary biologist at Auburn University in Alabama who was not involved with the work.

This means that early arachnids had a mix of all these traits, which were selectively lost in their descendants, giving rise to the array of arachnids seen today.

And what is even more amazing, says Bond, is that the amber is only 100 million years old. So these spider relatives hunted side by side with spiders for 200 million years.