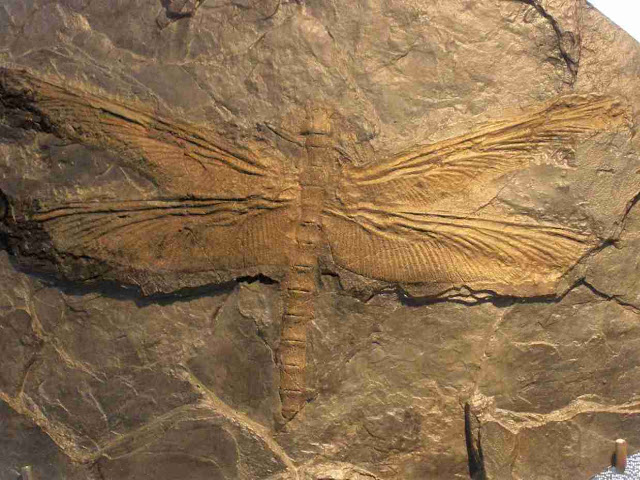

The Largest Insect Ever Existed Was A Giant ‘dragonfly’ Fossil Of A Meganeuridae

Meganeura the largest Flying Insect Ever Existed, Had a Wingspan of Up to 65 Cm, from the Carboniferous period.

Its name is Meganeuropsis, and it ruled the skies before pterosaurs, birds, and bats had even evolved.

The largest known insect of all time was a predator resembling a dragonfly but was only distantly related to them. Its name is Meganeuropsis, and it ruled the skies before pterosaurs, birds, and bats had even evolved.

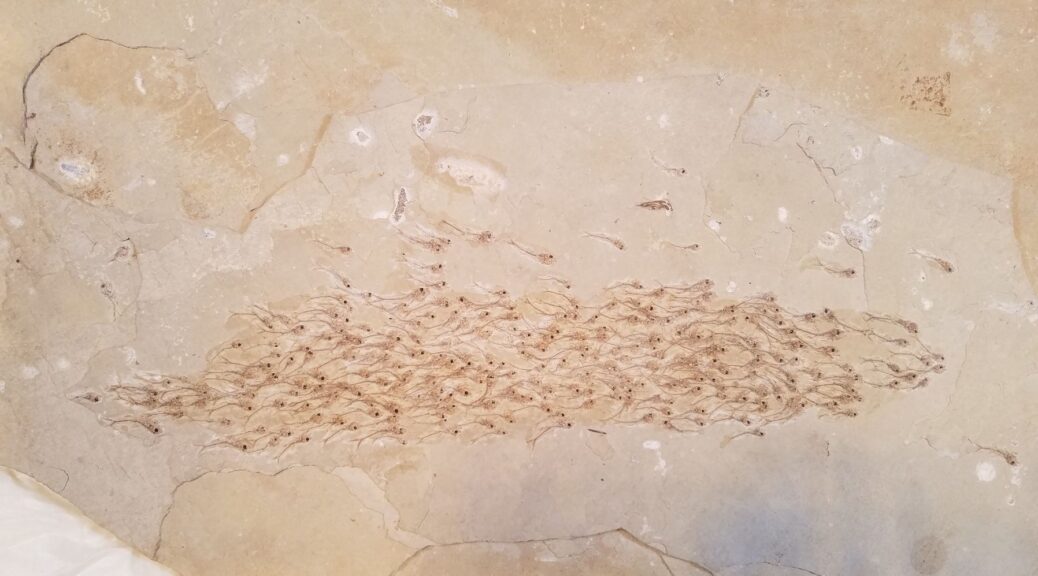

Most popular textbooks make mention of “giant dragonflies” that lived during the days before the dinosaurs. This is only partly true, for real dragonflies had still not evolved back then. Rather than being true dragonflies, they were the more primitive ‘griffin flies’ or Meganisopterans. Their fossil record is quite short.

They lasted from the Late Carboniferous to the Late Permian, roughly 317 to 247 million years ago.

The fossils of Meganeura were first discovered in France in the year 1880. Then, in 1885, the fossil was described and assigned its name by Charles Brongniart who was a French Paleontologist. Later in 1979, another fine fossil specimen was discovered at Bolsover in Derbyshire.

Meganisoptera is an extinct family of insects, all large and predatory and superficially like today’s odonatans, the dragonflies and damselflies. And the very largest of these was Meganeuropsis.

It is known from two species, with the type species being the immense M.permiana. Meganeuropsis permiana, as its name suggests is from the Early Permian.

There has been some controversy as to how insects of the Carboniferous period were able to grow so large.

•Oxygen levels and atmospheric density.

The way oxygen is diffused through the insect’s body via its tracheal breathing system puts an upper limit on body size, which prehistoric insects seem to have well exceeded. It was originally proposed hat Meganeura was able to fly only because the atmosphere at that time contained more oxygen than the present 20%.

•Lack of predators.

Other explanations for the large size of meganeurids compared to living relatives are warranted. Bechly suggested that the lack of aerial vertebrate predators allowed pterygote insects to evolve to maximum sizes during the Carboniferous and Permian periods, perhaps accelerated by an evolutionary “arms race” for an increase in body size between plant-feeding Palaeodictyoptera and Meganisoptera as their predators.

•Aquatic larvae stadium.

Another theory suggests that insects that developed in water before becoming terrestrial as adults grew bigger as a way to protect themselves against the high levels of oxygen.