15th-Century Theater Floorboards Uncovered in Norfolk

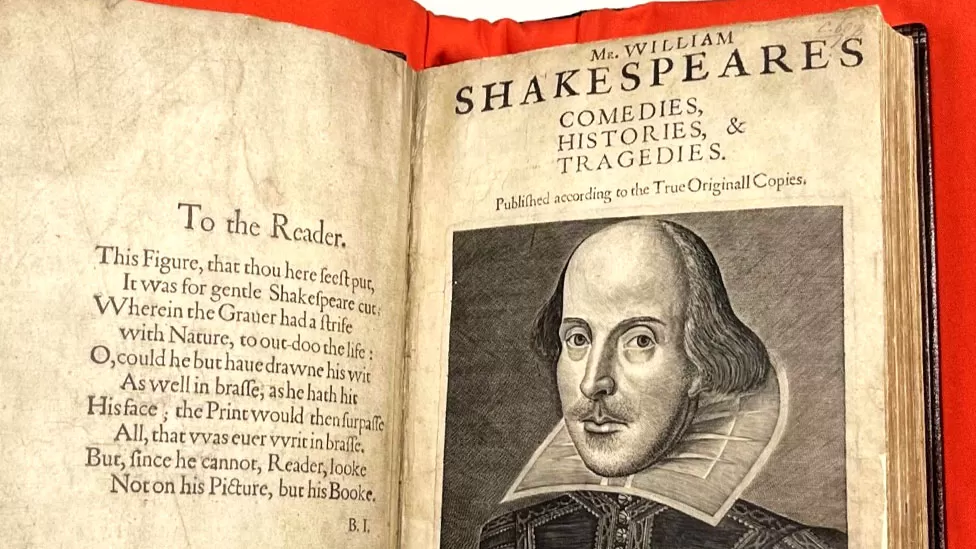

A theater in Norfolk believes it has discovered the only surviving stage on which William Shakespeare performed. St George’s Guildhall in King’s Lynn is the oldest working theater in the UK, dating back to 1445.

During recent renovations, timber floorboards were found under the existing auditorium, and they have been dated back to the 15th century. The theater claims documents show that Shakespeare acted at the venue in 1592 or 1593.

At the time, acting companies left the capital when theaters in London were closed due to the plague. The Earl of Pembroke’s Men, thought to include Shakespeare, visited King’s Lynn.

“We have the borough account book from 1592–93, which records that the borough paid Shakespeare’s company to come and play in the venue,” explains Tim FitzHigham, the Guildhall’s creative director.

The floorboards were uncovered last month during a renovation project at the Guildhall. They had been covered up for 75 years after a replacement floor was installed in the theater.

Dr. Jonathan Clark, an expert in historical buildings, was brought on board to research the venue. “We wanted to open up an area just to check, just to see if there was an earlier floor surviving here. And lo and behold, we found this,” he says, pointing through a temporary trapdoor.

A couple of inches below the modern floor are what he believes to be boards trodden by the Bard, each 12 inches (30cm) wide and 6 inches deep.

Dr. Clark used a combination of tree-ring dating and a survey of how the building was assembled (“really unusual as the boards locked together and were then pegged through to some massive bridging beams”) to date the floor to between 1417 and 1430 when the Guildhall was originally built.

“We know that these [floorboards] were definitely here in 1592, and in 1592 we think Shakespeare was performing in King’s Lynn, so this is likely to be the surface that Shakespeare was walking on,” he says.

“It’s this end of the hall where performances took place.”

Dr. Clark believes this is a hugely important discovery because not only is it the largest 15th-century timber floor in the country, but it would also be the sole surviving example of a stage on which Shakespeare acted.

“It’s the only upper floor, which is in something of its original state, where he could have been walking or performing,” he says.

There has been much academic debate over the years about whether Shakespeare did act in King’s Lynn, but experts say the discovery is significant.

Tiffany Stern, professor of Shakespeare and early modern drama at the University of Birmingham, tells the BBC: “The evidence he was there has to be patched together but is quite strong.”

It was “very likely” that he was a member of the Earl of Pembroke’s Men because they performed his plays Henry VI and Titus Andronicus, and they did visit King’s Lynn in 1593, she says.

Michael Dobson, director of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon, says: “The uncovering of the actual boards really trodden by Shakespeare’s troupe during their tours of East Anglia should be far more significant to archaeologists of the Elizabethan theatre than is the conjectural replica of the Globe theatre erected near the real, long-demolished Globe’s foundations in central London in the 1990s.”

Upstart crow

Back at the venue, FitzHigham believes a number of theories strengthen the argument that Shakespeare performed there.

Shakespeare’s comedian Robert Armin was born just one street away, he notes, while a Norfolk writer called Robert Greene famously described the Bard as an “upstart crow” in what was essentially a bad review in 1592.

The debate will continue. On Thursday, the discovery will be discussed at a talk at the venue called Revealing the Secrets of the Guildhall. Finally, FitzHigham takes me underneath the stage, making us squeeze between beams and using a torch, to allow a closer look at the huge expanse of medieval floorboards, which he explains is the size of a tennis court.

“600 years old,” he says with a real sense of wonder.

“Not just Shakespeare’s trodden on it, but everyone in between and we’re trying to make that safe and share it with everybody for the next hundreds of years going forward.”