Europe’s oldest known village teetered on stilts over a Balkan lake 8,000 years ago

Archaeologists in the Balkans have discovered the likely remains of an 8,000-year-old village built out over an ancient lake — the earliest-known village of any kind in Europe.

![Europe's oldest known village teetered on stilts over a Balkan lake 8,000 years ago Archaeologists in the Balkans have discovered the likely remains of an 8,000-year-old village built out over an ancient lake — the earliest-known village of any kind in Europe. The lake, located on the border between Albania and North Macedonia, holds hundreds of tree-trunk stilts that the archaeologists believe formed the foundations of the prehistoric village. The researchers can't yet estimate the settlement's original size — but their discovery of a defensive palisade of tens of thousands of wooden spikes, now underwater, indicates the village was relatively large. Albert Hafner, an archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland who led the excavations, told Live Science that divers sampled wood from the submerged tree trunks and wooden spikes near the Albanian village of Lin on the western shore of Lake Ohrid a few weeks ago. The results of dating tests won't be available for months. But Hafner said the submerged wood is probably the same age as wooden foundations unearthed on the shore, which his team determined date from between 5800 B.C. and 5900 B.C. This would mean it's the oldest settlement archaeologists have found anywhere in Europe, he said. Hafner's team also found evidence of similar "pile dwellings" built over the water at the underwater prehistoric site of Ploča Mičov Grad on the eastern shore of the lake — part of North Macedonia — but those remains date to a few hundred years later. It now seems both villages were built on opposite sides of the lake in phases over hundreds of years, and that the later building phases had obscured the earliest, he said. "It seems to be quite typical that we have multiple phases of settlements, with sometimes long gaps in between," he said. "It now looks like Lin dates mostly from the sixth millennium [B.C.] in several phases, starting in about 5900 and ending in 5000." First farmers Hafner has led the EXPLO project for several years, examining lakes in the Balkans for traces of settlers from Anatolia — now Turkey — to Europe about 8,000 years ago. They are thought to be the first people to bring farming to Europe from around Mesopotamia. The early farmers interbred with hunter-gatherers who had already occupied Europe since about 45,000 years ago during the Upper Palaeolithic period, and who probably arrived from Africa via the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. And both ancestries interbred with nomadic proto-Indo-European peoples like the Yamnaya, who arrived in Europe from the Eurasian Steppe about 5,000 years ago. Most modern Europeans show a genetic mix of all three ancestries. Hafner explained that the many large lakes in the Balkans region held clear traces of the early migration from Anatolia. Lake dwellers Hafner's team has so far investigated more than half a dozen sites across the Balkans. Research into some of the lake settlements was conducted in the 1960s. But the latest excavations use refined techniques like very accurate radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, which can determine when logs of wood were felled by looking at tree growth rings, Hafner said. Most of the former piles and stilts underwater near Lin are now covered by silt, but a few protrude from the lake floor. And archaeologists are unsure if the settlement was built in deep water or above mostly marshy ground. Ancient people were likely drawn to the lakes because of water and plants there. But exactly why prehistoric people chose to build their houses on piles or stilts above a lake or wetland isn't clear — though the practice is seen throughout Europe, from the Balkans to the Baltic. Hafner thinks that under normal conditions, it would have been easy to get between houses with dugout canoes. But the large palisade of wooden spikes indicates the village was sometimes attacked, he said; and houses on the water were more easily defended (although perhaps not always successfully).](https://archaeology-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Balkan-lake-1.1-1024x576.webp)

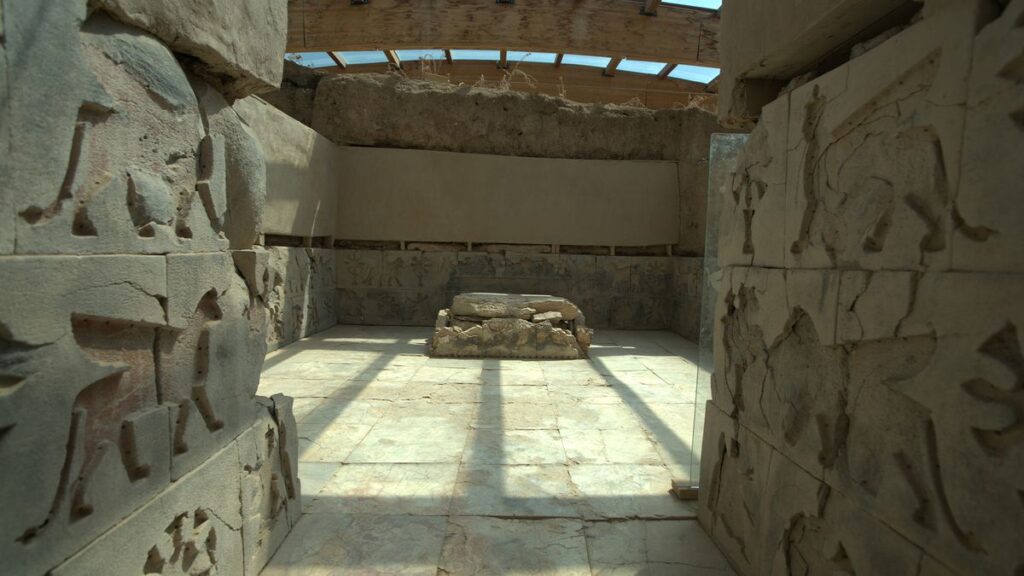

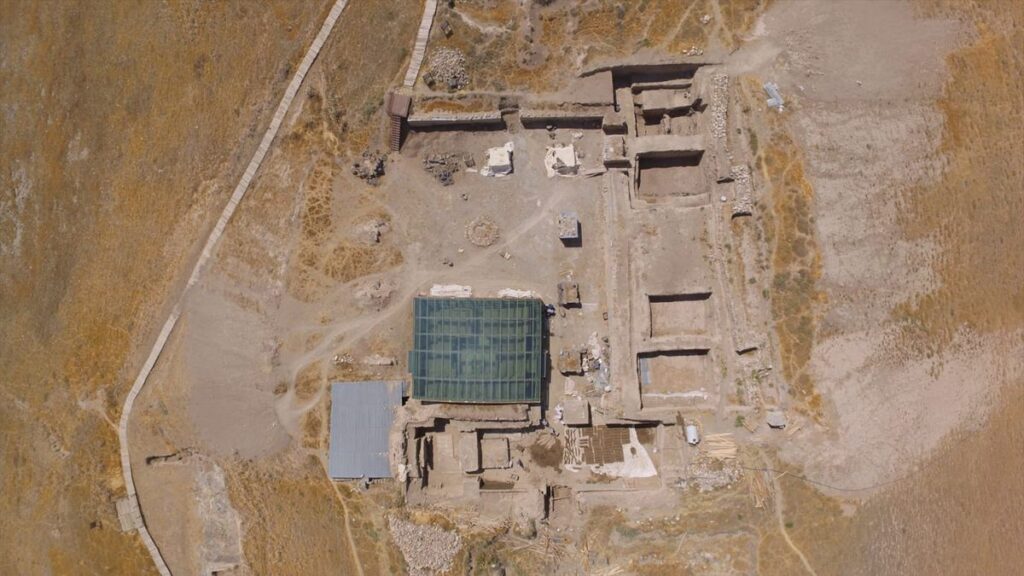

The lake, located on the border between Albania and North Macedonia, holds hundreds of tree-trunk stilts that the archaeologists believe formed the foundations of the prehistoric village.

The researchers can’t yet estimate the settlement’s original size — but their discovery of a defensive palisade of tens of thousands of wooden spikes, now underwater, indicates the village was relatively large.

Albert Hafner, an archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland who led the excavations, told Live Science that divers sampled wood from the submerged tree trunks and wooden spikes near the Albanian village of Lin on the western shore of Lake Ohrid a few weeks ago.

The results of dating tests won’t be available for months. But Hafner said the submerged wood is probably the same age as wooden foundations unearthed on the shore, which his team determined date from between 5800 B.C. and 5900 B.C.

This would mean it’s the oldest settlement archaeologists have found anywhere in Europe, he said.

Hafner’s team also found evidence of similar “pile dwellings” built over the water at the underwater prehistoric site of Ploča Mičov Grad on the eastern shore of the lake — part of North Macedonia — but those remains date to a few hundred years later.

It now seems both villages were built on opposite sides of the lake in phases over hundreds of years, and that the later building phases had obscured the earliest, he said.

“It seems to be quite typical that we have multiple phases of settlements, with sometimes long gaps in between,” he said. “It now looks like Lin dates mostly from the sixth millennium [B.C.] in several phases, starting in about 5900 and ending in 5000.”

First farmers

Hafner has led the EXPLO project for several years, examining lakes in the Balkans for traces of settlers from Anatolia — now Turkey — to Europe about 8,000 years ago. They are thought to be the first people to bring farming to Europe from around Mesopotamia.

The early farmers interbred with hunter-gatherers who had already occupied Europe since about 45,000 years ago during the Upper Palaeolithic period, and who probably arrived from Africa via the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

And both ancestries interbred with nomadic proto-Indo-European peoples like the Yamnaya, who arrived in Europe from the Eurasian Steppe about 5,000 years ago. Most modern Europeans show a genetic mix of all three ancestries.

Hafner explained that the many large lakes in the Balkans region held clear traces of the early migration from Anatolia.

Lake dwellers

Hafner’s team has so far investigated more than half a dozen sites across the Balkans.

Research into some of the lake settlements was conducted in the 1960s. But the latest excavations use refined techniques like very accurate radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, which can determine when logs of wood were felled by looking at tree growth rings, Hafner said.

Most of the former piles and stilts underwater near Lin are now covered by silt, but a few protrude from the lake floor. And archaeologists are unsure if the settlement was built in deep water or above mostly marshy ground.

Ancient people were likely drawn to the lakes because of water and plants there. But exactly why prehistoric people chose to build their houses on piles or stilts above a lake or wetland isn’t clear — though the practice is seen throughout Europe, from the Balkans to the Baltic.

Hafner thinks that under normal conditions, it would have been easy to get between houses with dugout canoes. But the large palisade of wooden spikes indicates the village was sometimes attacked, he said; and houses on the water were more easily defended (although perhaps not always successfully).

![Europe's oldest known village teetered on stilts over a Balkan lake 8,000 years ago Archaeologists in the Balkans have discovered the likely remains of an 8,000-year-old village built out over an ancient lake — the earliest-known village of any kind in Europe. The lake, located on the border between Albania and North Macedonia, holds hundreds of tree-trunk stilts that the archaeologists believe formed the foundations of the prehistoric village. The researchers can't yet estimate the settlement's original size — but their discovery of a defensive palisade of tens of thousands of wooden spikes, now underwater, indicates the village was relatively large. Albert Hafner, an archaeologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland who led the excavations, told Live Science that divers sampled wood from the submerged tree trunks and wooden spikes near the Albanian village of Lin on the western shore of Lake Ohrid a few weeks ago. The results of dating tests won't be available for months. But Hafner said the submerged wood is probably the same age as wooden foundations unearthed on the shore, which his team determined date from between 5800 B.C. and 5900 B.C. This would mean it's the oldest settlement archaeologists have found anywhere in Europe, he said. Hafner's team also found evidence of similar "pile dwellings" built over the water at the underwater prehistoric site of Ploča Mičov Grad on the eastern shore of the lake — part of North Macedonia — but those remains date to a few hundred years later. It now seems both villages were built on opposite sides of the lake in phases over hundreds of years, and that the later building phases had obscured the earliest, he said. "It seems to be quite typical that we have multiple phases of settlements, with sometimes long gaps in between," he said. "It now looks like Lin dates mostly from the sixth millennium [B.C.] in several phases, starting in about 5900 and ending in 5000." First farmers Hafner has led the EXPLO project for several years, examining lakes in the Balkans for traces of settlers from Anatolia — now Turkey — to Europe about 8,000 years ago. They are thought to be the first people to bring farming to Europe from around Mesopotamia. The early farmers interbred with hunter-gatherers who had already occupied Europe since about 45,000 years ago during the Upper Palaeolithic period, and who probably arrived from Africa via the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. And both ancestries interbred with nomadic proto-Indo-European peoples like the Yamnaya, who arrived in Europe from the Eurasian Steppe about 5,000 years ago. Most modern Europeans show a genetic mix of all three ancestries. Hafner explained that the many large lakes in the Balkans region held clear traces of the early migration from Anatolia. Lake dwellers Hafner's team has so far investigated more than half a dozen sites across the Balkans. Research into some of the lake settlements was conducted in the 1960s. But the latest excavations use refined techniques like very accurate radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, which can determine when logs of wood were felled by looking at tree growth rings, Hafner said. Most of the former piles and stilts underwater near Lin are now covered by silt, but a few protrude from the lake floor. And archaeologists are unsure if the settlement was built in deep water or above mostly marshy ground. Ancient people were likely drawn to the lakes because of water and plants there. But exactly why prehistoric people chose to build their houses on piles or stilts above a lake or wetland isn't clear — though the practice is seen throughout Europe, from the Balkans to the Baltic. Hafner thinks that under normal conditions, it would have been easy to get between houses with dugout canoes. But the large palisade of wooden spikes indicates the village was sometimes attacked, he said; and houses on the water were more easily defended (although perhaps not always successfully).](https://archaeology-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Balkan-lake-1.1-1038x576.webp)