In Medieval burial ground, a rare embroidered Deisis depicting Jesus Christ was discovered

Russian archaeologists have uncovered a rare embroidered Deisis depicting Jesus Christ in a medieval burial ground.

46 graves have been dug up during excavations; one of them contained a woman who was buried with an embroidered Deisis depicting Jesus Christ and John the Baptist and was between the ages of 16 and 25.

The discovery was made during the construction of the Moscow-Kazan highway, where archaeologists found an 8.6-acre medieval settlement and an associated Christian cemetery.

The iconography of Jesus Christ known as Deesis, which can be translated from Greek as “prayer” or “intercession,” is one of the most potent and prevalent images in Orthodox religious art.

The composition of the Deisis unites the three most important figures of Christianity. A tripartite icon of the Eastern Orthodox Church showing Christ usually enthroned between the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist.

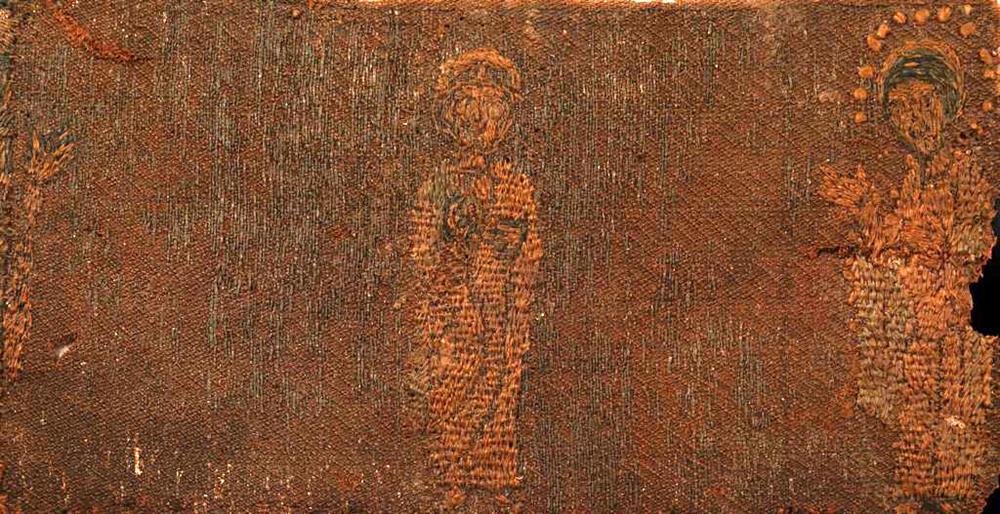

The fabric is 12.1 cm long by 5.5 cm wide and is composed of two parts joined by a vertical seam made of a woven gold ribbon with a braided pattern.

The fabric’s lining did not survive, but a microscopic examination revealed birch bark remnants and needle punctures along the lower and upper edges.

In the center of the fabric is a frontal image of Jesus Christ making a blessing gesture, and to the right of him is John the Baptist praying. A second figure, probably Mary, was once on the left, but it has since disappeared, according to the inspection.

The archaeologists believe the embroidered fabric was once a dark silk samite headdress.

Similar examples include the embroidered crosses and faces of saints discovered in the Karoshsky burial ground in the Yaroslavl region, as well as the Ivorovsky necropolis near Staritsa that features an image of Michael the Archangel wielding a spear.