Iraq says the US returning 17,000 looted ancient treasures

Next month, museum-goers in Iraq are in for a surprise. Eighteen years after it was looted from the city, a clay tablet bearing the Epic of Gilgamesh, regarded as one of the world’s oldest surviving pieces of literature, is set to return to the place of its birth.

Iraq Tuesday reclaimed more than 17,000 ancient artefacts looted and smuggled out of the country after the US invasion in 2003, reported The New York Times.

About 12,000 of the returned artifacts had been housed in the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC and 5,381 had been held by Cornell University. Both institutions have been pulled up by US authorities in the past for holding artifacts that were not acquired through appropriate means.

Iraqi culture and foreign ministries disclosed to the NYT that US authorities had reached an agreement with Iraq to return items seized from dealers and museums in the US. Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi brought back the artifacts on his plane, after making an official visit to the US last week.

After 1991, when the Iraqi government lost control of parts of southern Iraq following the first Gulf War, widespread looting occurred at historical sites. The looting continued after the US-led invasion in 2003 — the year that also witnessed the end of the Saddam Hussein regime.

Many artefacts were also smuggled or destroyed by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) militants during the period between 2014 and 2017 when it controlled some parts of Iraq.

The Gilgamesh tablet

The Gilgamesh tablet is a prized and much-anticipated retrieval.

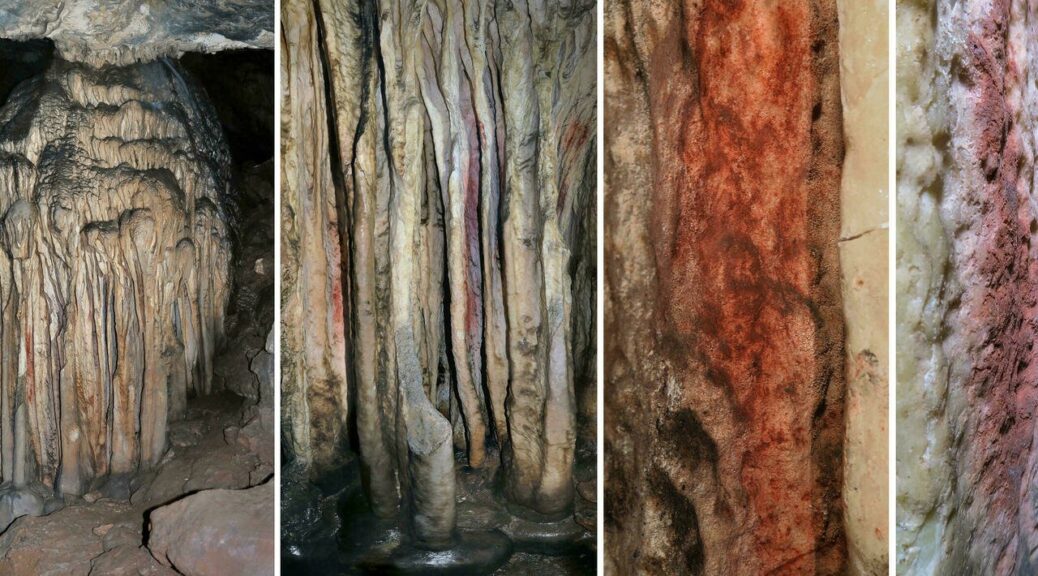

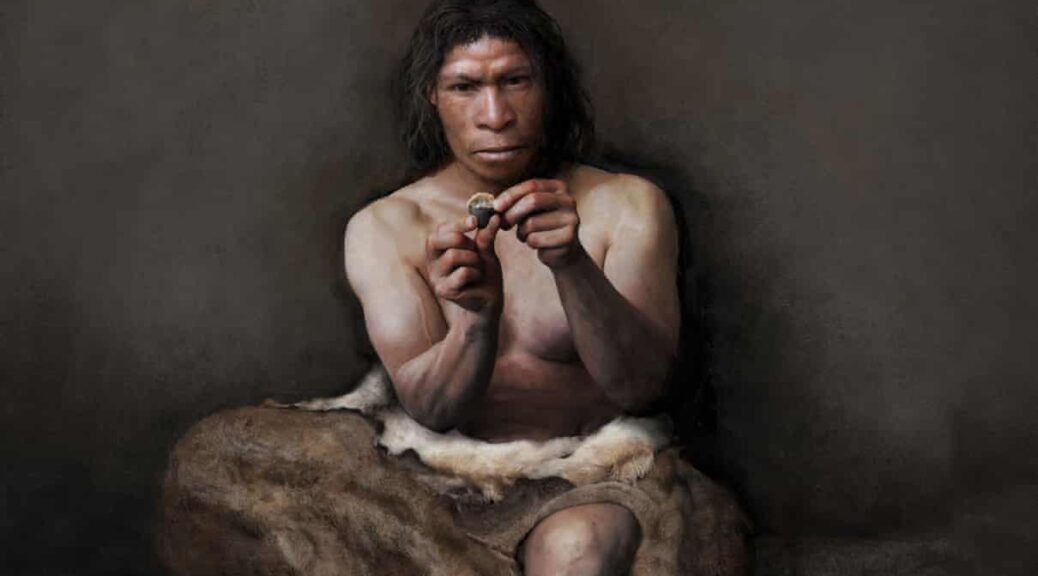

The 3,500-year-old clay tablet bearing the Epic of Gilgamesh is considered one of the world’s first pieces of notable literature. The epic is believed to predate Homer’s Iliad by 1,500 years and is one of the beloved tales of Mesopotamia — present-day Iraq.

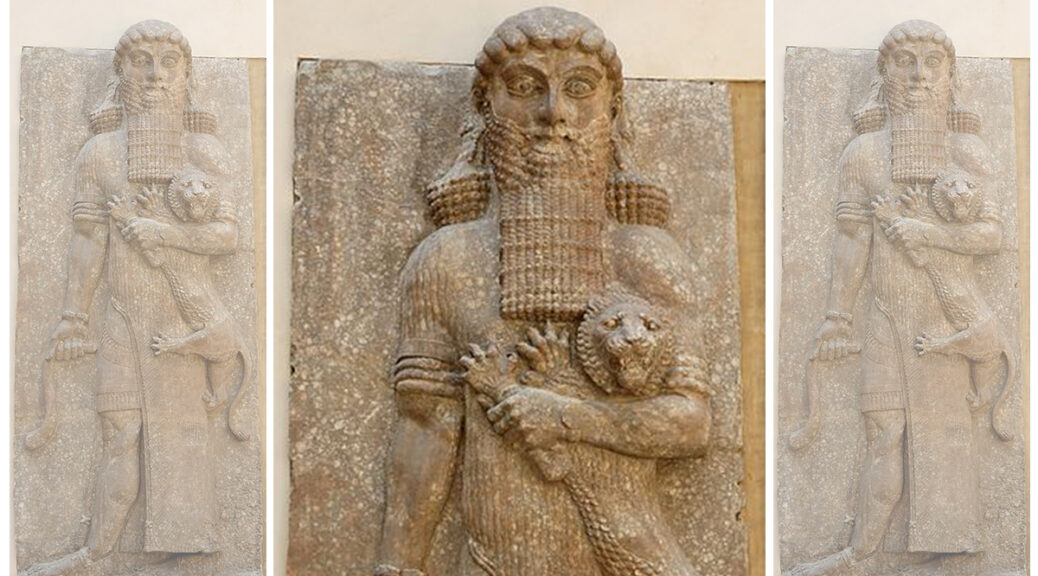

The epic is based on the many adventures of the handsome athletic king of Uruk, Gilgamesh (2900–2350 BC).

Many of the other clay tablets and seals that have been returned by the US also are linked to Mesopotamia — one of the world’s earliest civilisations — and even to Irisagrig, a lost ancient city.

The tablet will return to Iraq in September after legal procedures are wrapped up, Iraq’s Culture Minister Hassan Nadhem told Reuters. Speaking on the cultural value of the artifacts, he told The New York Times: “This is not just about thousands of tablets coming back to Iraq again — it is about the Iraqi people.”

Back to places of origin

In 2013, the US Justice Department urged Cornell University to give back thousands of ancient tablets believed to have been looted from Iraq in the 1990s, according to the Los Angeles Times.

In 2019, US authorities seized the Gilgamesh tablet displayed at the Washington museum after it was revealed to have been smuggled, auctioned and sold to an art dealer in Oklahoma.

An American antiquities dealer had bought the tablet from a London-based dealer in 2003, the US Department of Justice said in a statement last week.

Australia, too, in a statement last week, announced it would return 14 works of art, worth a combined $3 million, to the Indian government.