CT Scans Suggest Egyptian Pharaoh Was Brutally Executed on the Battlefield

Seqenenre Taa II, the Egyptian pharaoh, may have died on the battlefield, surrounded by attackers carrying daggers, swords, and spears. According to a recent computed tomography (CT) scan of the pharaoh’s damaged mummy, which revealed new facial wounds that ancient embalmers tried to disguise.

A broad cut in the pharaoh’s forehead, wounds across his eyes and cheeks, and a knife wound at the base of the skull that may have penetrated the brain stem were all visible. The attackers, it seems, surrounded the defeated ruler on every side.

“This suggests that Seqenenre was really on the front line with his soldiers, risking his life to liberate Egypt,” study lead author Sahar Saleem, a professor of radiology at Cairo University, said in a statement.

A war over hippos

Seqenenre Taa II (also spelled Seqenenre Tao II) was the ruler of southern Egypt between about 1558 B.C. and 1553 B.C., during the occupation of Egypt by the Hyksos, a people who probably came from the Levant.

The Hyksos controlled northern Egypt and required tribute from the southern part of the kingdom.

According to fragmentary papyrus accounts, Seqenenre Taa II revolted against the occupiers after receiving a complaint from the Hyksos king that the noise of hippos in a sacred pool in Thebes was disturbing his sleep.

The king lived in the capital city of Avaris, 400 miles (644 kilometres) away. On this trumped-up charge, the Hyksos king demanded the sacred pool be destroyed — a grave insult to Seqenenre Taa II.

This insult may have been the prelude to war. Text on a carved rock slab found in Thebes recounts that Seqenenre Taa II’s son and immediate successor, Kamose, died in battle against the Hyksos.

No one knew what had happened to the pharaoh, even after his mummy was discovered in 1886. Archaeologists noticed wounds on the skull and speculated that he’d been killed in battle or perhaps murdered in a palace coup. The 19th-century archaeologists who found the mummy reported a foul smell when they unwrapped it, leading them to suspect that the mummy had been hastily embalmed on the battlefield.

The new study uses X-rays from multiple angles to build a 3D image of the pharaoh’s mummy. The pharaoh’s remains are in poor condition, with bones disarticulated and the head detached from the rest of the body.

Violent death

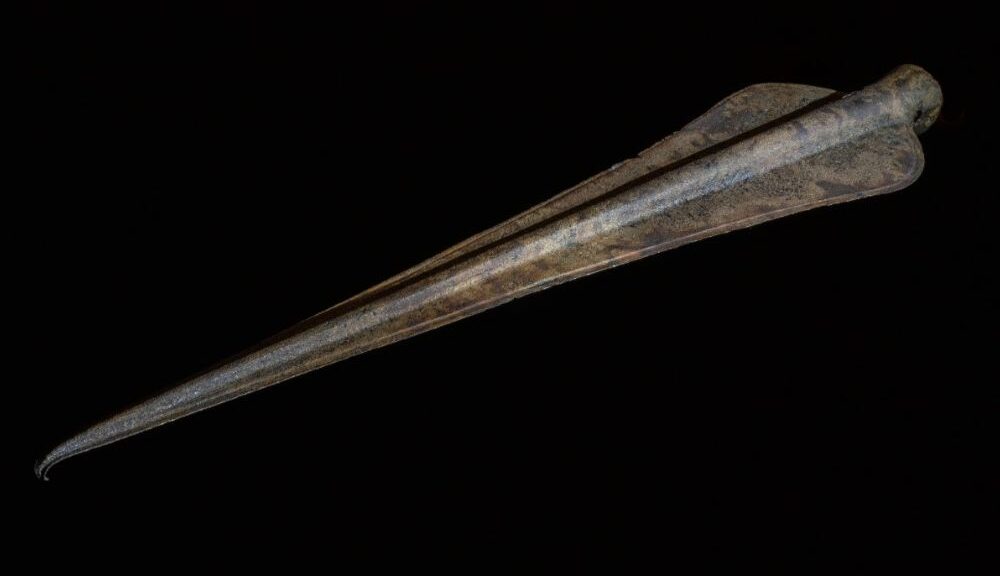

Nevertheless, the wounds on the skull tell the story of brutal death. The pharaoh had a 2.75-inch-long (7 centimeters) cut across his forehead, which would have been delivered from an axe or sword stroke from above. This wound alone could have been fatal. Another potentially fatal slice above the pharaoh’s right eye was 1.25 inches (3.2 cm) long and possibly made by an axe. More cuts on the nose, right eye and right cheek came from the right and from above and may have been delivered with an axe handle or blunt staff, the researchers said.

Meanwhile, someone in front of the king swung a sword or an axe at the pharaoh’s left cheek, leaving another deep slice. From the left, a weapon — probably a spear — penetrated the base of his skull, leaving a 1.4-inch-long (3.5 cm) wound.

Early archaeologists had previously reported many of these wounds, but Saleem and her colleague, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, discovered a new set of skull fractures covered by embalming material. Concentrated on the right side of the skull, the damage seems to have been caused by a dagger and a heavy, blunt object, perhaps an axe handle.

The mummy’s hands were flexed and clenched, but there were no defensive injuries on his forearms, leading the researchers to suggest that perhaps Seqenenre Taa II’s hands were bound when he died. He may have been captured on the battlefield and executed by multiple attackers, Saleem said in the statement.

Although researchers have discovered pharaoh mummies with violent wounds before, there had been no evidence of pharaoh battlefield deaths until now, Saleem told Live Science. For example, Ramesses III had his throat cut in a palace coup, she said. Historical accounts tell of Ramesses II and Thutmose III taking part in the battle, but there is no evidence of injuries on their mummies. The mummy of an unidentified nobleman had an arrow embedded in its chest, Saleem said, which may have occurred in battle.

The fact that embalmers tried to patch up Seqenenre Taa II’s skull wounds suggests that he wasn’t hastily embalmed, the researchers wrote in their new study, in the journal Frontiers in Medicine.

The pharaoh’s desiccated brain was also stuck to the left side of his skull, suggesting that someone laid him on his side after his death, either at the place where he fell or while his body was being transported for embalming.

Seqenenre Taa II may have lost his life in battle, but his successors eventually won the war. After Kamose died, Seqenenre Taa II’s consort, Ahhotep I, likely acted as regent, continuing the rebellion against the Hyskos. When Seqenenre Taa II and Ahhotep I’s son Ahmose I came of age, he inherited the throne and finally pushed out the foreign occupiers. Ahmose I would unify Egypt and launch the New Kingdom, the period of ancient Egypt’s peak power between the 16th and 11th centuries B.C.