The ancient buried city of Akrotiri, Santorini: Greece Pompeii

The ruins of a Bronze Age sophisticated settlement that thrived centuries before being eradicated by a major volcanic eruption are tucked away from the southern tip of Santorini.

The remains of the Minoan town of Akrotiri are remarkably well preserved, like the Roman ruins of Pompei. In the middle of the second millennium BC, the settlement erupted, when Thera sat on a volcano, and its people fled.

The volcanic matter enveloped the entire island of Santorini and the town itself, preserving the buildings and their contents, and visitors can still identify houses and pots.

The settlement of Akrotiri is one such site. Unlike Pompeii, however, no literary evidence for the destruction of Akrotiri is available to us. As a matter of fact, the city was only discovered by an archaeological excavation conducted in 1967.

Akrotiri was a Bronze Age settlement located on the southwest of the island of Santorini (Thera) in the Greek Cyclades. This settlement is believed to be associated with the Minoan civilization, located on the nearby island of Crete, due to the discovery of the inscriptions in Linear A script, as well as similarities in artifacts and fresco styles.

The earliest evidence for human habitation of Akrotiri can be traced back as early as the 5 th millennium B.C. when it was a small fishing and farming village. By the end of the 3 rd millennium, this community developed and expanded significantly.

One factor for Akrotiri’s growth may be the trade relations it established with other cultures in the Aegean, as evidenced in fragments of foreign pottery at the site. Akrotiri’s strategic position between Cyprus and Minoan Crete also meant that it was situated on the copper trade route, thus allowing it to become an important center for processing copper, as proven by the discovery of molds and crucibles there.

Akrotiri’s prosperity continued for about another 500 years. Paved streets, an extensive drainage system, the production of high-quality pottery, and further craft specialization all point to the level of sophistication achieved by the settlement. This all came to an end, however, by the middle of the 2 nd century B.C. with the volcanic eruption of Thera. Although the powerful eruption destroyed Akrotiri, it also managed to preserve the city, very much like that done by Vesuvius to Pompeii.

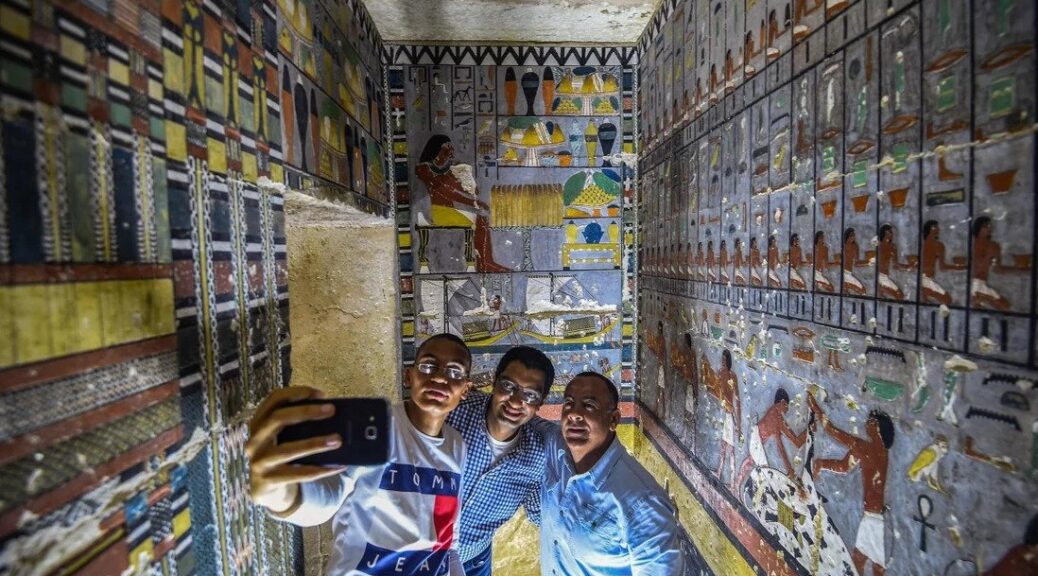

The volcanic ash has preserved much of Akrotiri’s frescoes, which can be found in the interior walls of almost all the houses that have been excavated in Akrotiri. This may be an indication that it was not only the elites who had these works of art.

The frescoes contain a wide range of subjects, including religious processions, flowers, everyday life in Akrotiri, and exotic animals. In addition, the volcanic dust also preserved negatives of disintegrated wooden objects, such as offering tables, beds, and chairs.

This allowed archaeologists to produce plaster casts of these objects by pouring liquid Plaster of Paris into the hollows left behind by the objects. One striking difference between Akrotiri and Pompeii is that there were no uninterred bodies from in the former. In other words, the inhabitants of Akrotiri were perhaps more fortunate than those of Pompeii and were evacuated before the volcanic dust reached the site.

In 2016, Russian cybersecurity expert Eugene Kaspersky gave archaeologists interested in excavating Akrotiri a huge economic boost by funding three major projects at the ancient site. This is how he explained his reason for financial support:

“What I find magical about Akrotiri and the decades-long, ongoing archaeological research is the sense of an unpredictable past. The fact that following a volcano eruption 3,500 years ago, we modern people are trying to comprehend how these people lived back then. And I believe that we have plenty to discover. Do you think that 3,500 years from now anyone will be interested in finding out how we lived?”

The eruption of Thera also had an impact on other civilizations. The nearby Minoan civilization, for instance, faced a crisis due to the volcanic eruption. This is debatable, however, as some have speculated that the crisis was caused by natural disasters occurring prior to the eruption of Thera.

The short term climate change caused by volcanic eruption is also believed to have disrupted the ancient Egyptian civilization. The lack of Egyptian records regarding the eruption may be attributed to the general disorder in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period.

Nevertheless, the available records speak of heavy rainstorms occurring in the land, which is an unusual phenomenon. These storms may also be interpreted metaphorically as representing the elements of chaos that needed to be subdued by the Pharaoh.

Some researchers have even claimed that the effects of the volcanic eruption were felt as far away as China. This is based on records detailing the collapse of the Xia Dynasty at the end of the 17th century B.C., and the accompanying meteorological phenomena. Finally, the Greek myth of the Titanomachy in Hesiod’s Theogony may have been inspired by this volcanic eruption, whilst it has also been speculated that Akrotiri was the basis of Plato’s myth of Atlantis.

Thus, Akrotiri and the eruption of Thera serve to show that even in ancient times, a catastrophe in one part of the world can have repercussions on a global scale, something that we are more used to in the better-connected world of today.