Three Settlements Unearthed in Southern Bulgaria

In three rescue excavations near the town of Radnevo, three different ancient settlements are discovered funded by a coal mining company, the most interesting was a new artefact was a statuette of the ancient goddess Athena, an early Thracian settlement a town from the time of the Roman Empire, and an early Byzantine and mediaeval Bulgarian settlement.

The rescue excavations have been carried out by the Maritsa East Archaeological Museum in Radnevo with funding from the Maritsa East Mines Jsc company, a large state-owned coal mining company, on plots slated for coal mining operations.

An Early Ancient Thracian settlement has been discovered in the first researched location to the west of the town of Polski Gradets, Radnevo Municipality, Stara Zagora District, (in an area called “Dyado Atanasovata Mogila”), the Maritsa East Mines company has announced.

The Maritsa East Archaeological Museum has not announced the precise dating of the site but the Early Thracian period would typically refer to ca. 1,000 BC, the Early Iron Age.

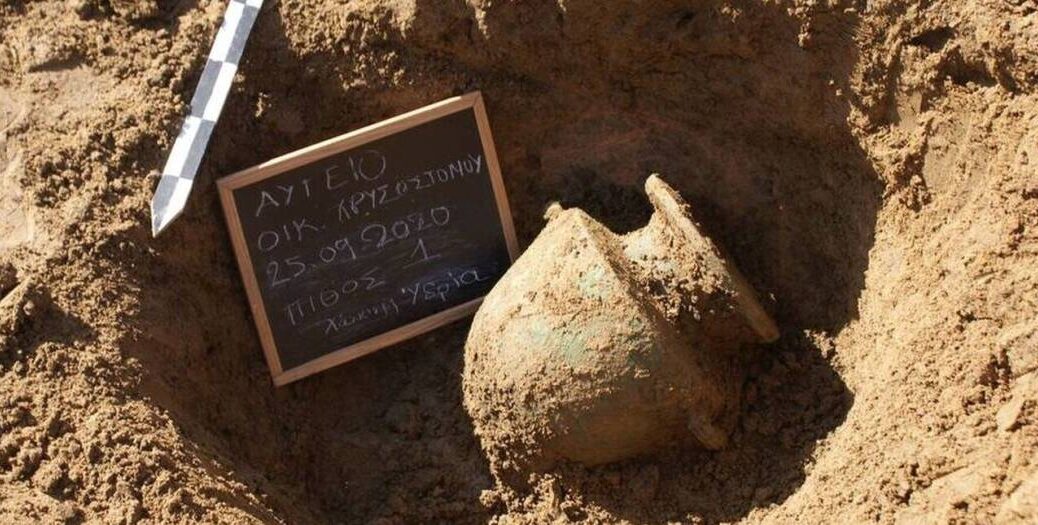

The rescue excavations on the site of the Early Thracian settlements were carried out in September and October 2020 by a team led by Assoc. Prof. Krasimir Nikov and Assoc. Prof. Rumyana Georgieva, both of them archaeologists from the National Institute and Museum of Archaeology in Sofia.

The archaeologists have discovered the ruins of Thracian residential and “economic” buildings. The artefacts discovered in the site include anthropomorphic figurines, pottery vessels, ceramic spindle whorls, loom weights, millstones, stone tools used for polishing and hammering. Inside the ritual pits of the Early Thracian settlement near Radnevo, the archaeologists have found human burials.

In them, the humans were buried in a fetal position (in archaeological texts in Bulgaria and some other European and Asian countries, it is known as the “hocker position” – in which the knees are tucked against the chest).

The Maritsa East Museum says that the discovery of the Early Thracian settlement has yielded new “information about the settlement structure of the Thracian Age.”

In the second location subject to rescue excavations near Bulgaria’s Radnevo (in an area called “Boyalaka”), an archaeological team has found the periphery of a settlement from the 2nd – 4th century AD, i.e. the period of the Roman Empire, which also existed in later periods, all the way into the Middle Ages.

The excavations in question have covered a large area of about 40 decares (10 acres) on a plot slated for coal mining. The archaeological team has performed a total of 32 drillings at selected spots in order to designate areas for further more detailed excavations.

On the surface, the archaeologists have found pottery from different time periods – from the Roman Era, the Early Byzantine Era, the Middle Ages, and the Late Middle Ages – the time of the medieval Bulgarian Empire. The archaeologists have unearthed bricks, tegulae, and a glazed plate from the Late Antiquity period.

“We assume this was the periphery of a settlement from the Roman Era – 2nd – 4th century AD, which developed in the western direction. The eight [Roman] coins that we have found during the drillings also confirm this dating,” says Plamen Karailiev, Director of the Maritsa East Archaeological Museum in Radnevo. The most interesting artefact from the Roman Era settlement in question is a bronze statuette depicting Ancient Thracian, Greek, and the Roman goddess Athena.

“What’s generating interest is the bronze statuette depicting goddess Athena, which is the first of its kind to become part of the collection of [our] museum,” the museum director states. In the same location, however, the archaeologists have also discovered for the first time pottery fragments from the Bronze Age, which the Museum says is adding information to the site’s stratigraphy for future excavations to precede the coal mining there.

The third location excavated at the request of the state mining company near Radnevo in 2020 is near the town of Troyanovo (in an area called “Vehtite Lozya”), where an archaeological team has discovered structures from a settlement from the Early Byzantine period, i.e. Late and Antiquity and Early Middle Ages, and from the medieval period when the region at different times was part of the First and Second Bulgarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire).

There the archaeological team led by Krasimir Velkov from the Tvarditsa Museum of History and Tatyana Kancheva from the Maritsa East Museum of Archaeology has found a wide range of early medieval and medieval structures.

These include a total of 12 dwellings, 7 semi-dugouts which, however, were not used as homes, i.e. for residential purposes, a total of 14 pits, two household kilns and one hearth. The excavations of the “layer settlement from the Early Byzantine and medieval period” covered an area of 4 decares (app. 1 acre), and were carried out from early August until early October 2020.

The wide range of archaeological artefacts discovered on the site including a number of coins, including two Byzantine “cup-shaped” coins, the so-called scyphates, fragments from bronze and glass bracelets, an iron spur, iron arrow tips, small knives, an iron fishing hook, numerous spindle whorls, clay candlesticks, and lids of pottery vessels.

The 2020 rescue archaeological excavations in all three locations around the town of Radnevo, which is the largest coal mining area in Bulgaria, have been funded by the state-owned Maritsa East Mines company with a combined total of more than BGN 240,000 (app. EUR 120,000).

In a release, the Maritsa East Mines company points out that the first-ever rescue archaeological excavations in the area of Radnevo in Southern Bulgaria were carried out back in 1960 right at the start of the industrial coal mining there.

“For many decades now, Maritsa East Mines Jsc have contributed to the preservation of artefacts from past millennia. The extraction of coal begins only after the respective plots have been researched by archaeologists. The finds from these rescue archaeological expeditions, some of which are unique, have been processed and exhibited at the Maritsa East Museum of Archaeology in Radnevo,” the state-owned company says.

A very interesting archaeological artefact discovered during rescue excavations near Radnevo funded by the coal mining conglomerate has been an Ancient Thracian clay altar from the 4th century BC.