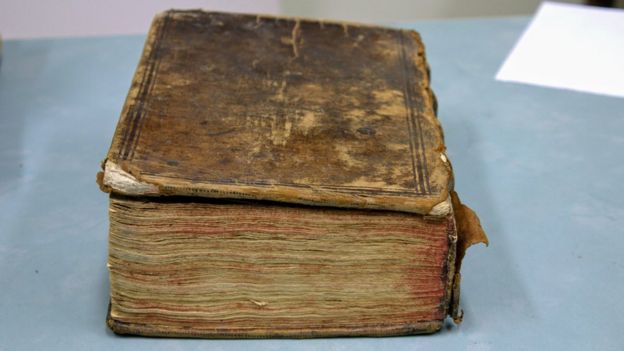

Couple find £5,000,000 in one of biggest ever treasure hoards

In an area in Somerset, in the West of England, a pair of metal detectorists found their existence when they uncovered a hoard of ancient coins worth about 6 million dollars.

The historical discovery, which has been deemed to be one of the greatest hidden treasures in the UK, is to be revealed in the British Museum.

The 2,571 Anglo-Saxon and Norman coins were unearthed by Adam Staples ‘ and Lisa Grace Treasure hunters when they searched farmland with their trusty metal detectors. The couples have described the hoard as “stunning” and “absolutely mind-blowing” in an interview with Treasure Hunting Magazine.

They reported their find to the authorities as required by UK law, and the coins were soon sent to the British Museum for evaluation.

The British Museum has been assessing the find for the past seven months and is due to reveal more information about the coins to the public next week.

A spokesperson for the institution confirmed to the Daily Mail that the “large hoard” was handed over as possible treasure and that it appears to be “an important discovery.”

Under the UK’s 1996 Treasure Act, if a find is officially declared treasure, it must first be offered for sale to a museum at a price set by the British Museum’s Treasure Valuation Committee. If no museum can raise the money to acquire the coins, they can then be offered for sale at auction.

The owner of the land where the coins were found is entitled to half of the proceeds. The metal detectorists are keeping the exact location of their discovery under wraps, although the trove is called the Chew Valley Hoard after an area in North Somerset.

A coin expert at the London auctioneers Dix Noonan Webb has valued the coins at around £5 million ($6 million).

They include mint-condition silver King Harold II pennies, coins from the reign of William the Conqueror, which could be worth as much as £5,000 ($6,000) each, as well as pieces minted by previously-unknown moneyers.

The King Harold II coins are particularly rare due to his short reign. The last Anglo-Saxon king was on the throne for just nine months before he died during the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The expert said that the hoard may prove too pricey for museums, which might have to launch an appeal for sponsors to raise funds to acquire them.

The coins would have belonged to a wealthy person who probably buried them for safekeeping at some point after the Norman Invasion of 1066 and probably before 1072.

The biggest collection of buried treasure ever discovered in the UK was the Staffordshire Hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork, but this latest find could worth $1 million more, and have as great or even more historic value.