City wall discovered that’s 1,000 years older than Rome, lost civilization found in China

The ancient walls of a lost city in southern China have been uncovered in a remarkable find by archaeologists. The northern section of the city was found at the Sansingdui archaeological site located in Sichuan province. It dates back than 3,000 years to the Bronze Age.

The Southern, Western, and Eastern sections fo the city have now been uncovered as well, granting archaeologists a full picture of what the settlement used to look like. Three Neolithic tombs thought to have predated the walls have also been unearthed, with one including a full human skeleton.

In 1929, a farmer digging a new well discovered a stash of jade relics, which led Chinese archaeologists to excavate the area around the village.

Nothing came of these explorations until 1986 when two enormous sacrificial pits were found. Uncovered from the pits were thousands of pottery, jade, bronze, and gold artifacts that were not seen elsewhere in China before.

This exciting find led to a whole new understanding of the development of Chinese culture. The artifacts were dated as being 3,000 to 5,000 years old, and archaeologists knew they were examining a previously unknown ancient culture that had developed thousands of miles from civilizations of a similar age.

The artifacts showed evidence of having been burned or broken before they were carefully buried; however, this doesn’t detract from the magnificence of the find.

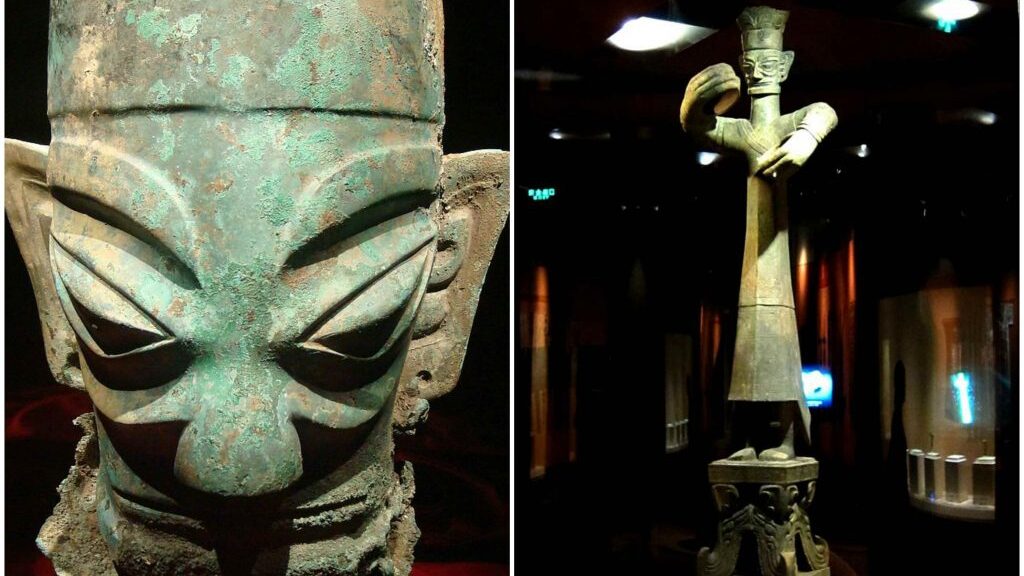

The dig uncovered sculptures with animal faces, masks with dragon features, human-style heads with masks on, figurines of animals such as dragons, birds, and snakes all beautifully decorated, as well as a sacrificial altar, a bronze tree, rings, knives, and other decorative items. The most unusual item found was an eight-foot-tall human figure made of bronze.

The archaeologists were surprised to find numerous bronze masks and human heads that have square faces, huge almond-shaped eyes, long straight noses, and exaggerated ears.

These were carbon dated and found to be from the 12th to 11th century BC, and the well-developed technology used to create these bronzes astounded the scientists.

The ancient Chinese metallurgists knew that adding lead to an amalgam of copper and tin gave them a stronger substance that they could use to create large items such as the human and the tree.

One of the masks, the largest ever found anywhere, measured an astounding 1.32 meters wide and 0.72 meters tall. The animal-like ears, protruding eyes, and ornate bodies of these masks demonstrated an artistic style unique from any other found in China.

Unfortunately, no written texts have been located at Sanxingdui to help scientists unravel the mysteries of the city. This Bronze Age civilization, which is now known as the Sanxingdui Culture, has been associated with the ancient kingdom of Shu; the rich artifacts have been attributed to the legendary kings of Shu.

There may be few reliable records that link this civilization to the kingdom of Shu, but the Chronicles of Huayang that were written in the Jin Dynasty, which existed from 265-420 AD, tell of the Shu Kingdom being founded by the Cancong. These people were described as having bulging eyes, a common feature of the artifacts found at Sanxingdui.

This amazing civilization was at its prime around 3,000 to 5,000 years ago, and the city was then completely abandoned.

The question that is facing archaeologists now is – why? A theory has been put forward that a major earthquake hit the region, causing landslides that blocked the water supply to the city, so the residents had to leave their city and move closer to the river. This theory has not been proven.