Archaeologists Have a Lot of Dates Wrong for North American Indigenous History — But Are Using New Techniques to Get It Right

It was in 1492 that Columbus reached the Americas. Many Europeans had travelled before, but the century from then until 1609 marks the creation of the modern globalized world.

It gave Europe extraordinary wealth and genocide and disease to indigenous peoples across the Americas.

The dates and the estimates of the settlement in Europe are known from texts and sometimes illustrations, to use the failed colony on what was then Virginia’s Roanoke Island as an example.

However, one thing is missing. What of indigenous history in this traumatic era? Until now, the standard timeline has derived, inevitably, from the European conquerors, even when scholars try to present an indigenous perspective.

This all happened just 400 to 500 years ago – how wrong could the conventional chronology for indigenous settlements be? Quite wrong, it turns out, based on radiocarbon dating my collaborators and I have carried out at a number of Iroquoian sites in Ontario and New York state. We’re challenging existing – and rather colonialist – assumptions and mapping out the correct time frames for when indigenous people were active in these places.

Refining Dates Based on European Goods

Archaeologists estimate when a given indigenous settlement was active based on the absence or presence of certain types of European trade goods, such as metal and glass beads. It was always approximate, but became the conventional history.

Since the first known commercial fur trading missions were in the 1580s, archaeologists date initial regular appearances of scattered European goods to 1580-1600. They call these two decades Glass Bead Period 1. We know some trade occurred before that, though, since indigenous people Cartier met in the 1530s had previously encountered Europeans, and were ready to trade with him.

Archaeologists set Glass Bead Period 2 from 1600-1630. During this time, new types of glass beads and finished metal goods were introduced, and trade was more frequent. The logic of dating based on the absence or presence of these goods would make sense if all communities had equal access to, and desire to have, such items. But these key assumptions have not been proven.

That’s why the Dating Iroquoia Project exists. Made up of researchers here at Cornell University, the University of Georgia, and the New York State Museum, we’ve used radiocarbon dating and statistical modeling to date organic materials directly associated with Iroquoian sites in New York’s Mohawk Valley and Ontario in Canada.

First we looked at two sites in Ontario: Warminster and Ball. Both are long argued to have had direct connections with Europeans. For instance, Samuel de Champlain likely stayed at the Warminster site in 1615-1616. Archaeologists have found large numbers of trade goods at both sites.

When my colleagues and I examined and radiocarbon dated plant remains (maize, bean, plum) and a wooden post, the calendar ages we came up with are entirely consistent with historical estimates and the glass bead chronology. The three dating methods agreed, placing Ball circa 1565-1590 and Warminster circa 1590-1620.

However, the picture was quite different at several other major Iroquois sites that lack such close European connections. Our radiocarbon tests came up with substantially different date ranges compared with previous estimates that were based on the presence or absence of various European goods.

For example, the Jean-Baptiste Lainé, or Mantle, site northeast of Toronto is currently the largest and most complex Iroquoian village excavated in Ontario. Excavated between 2003–2005, archaeologists dated the site to 1500–1530 because it lacks most trade goods and had just three European-source metal objects. But our radiocarbon dating now places it between about 1586 and 1623, most likely 1599-1614. That means previous dates were off the mark by as much as 50 to 100 years.

Other sites belonging to this same ancestral Wendat community are also more recent than previously assumed. For example, a site called Draper was conventionally dated to the second half of the 1400s, but radiocarbon dating places it at least 50 years later, between 1521 and 1557. Several other Ontario Iroquoian sites lacking large trade good assemblages vary by several decades to around 50 years or so from conventional dates based on our work.

My colleagues and I have also investigated a number of sites in the Mohawk Valley, in New York state. During the 16th and early 17th centuries, the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers formed a key transport route from the Atlantic coast inland for Europeans and their trade goods. Again, we found that radiocarbon dating casts doubt on the conventional time frame attributed to a number of sites in the area.

Biases That Led to Misguided Timelines

Why were some of the previous chronology wrong?

The answer seems to be that scholars viewed the topic through a pervasive colonial lens. Researchers mistakenly assumed that trade goods were equally available, and desired, all over the region, and considered all indigenous groups as the same. On the contrary, it was Wendat custom, for example, that the lineage whose members first discovered a trade route claimed rights to it. Such “ownership” could be a source of power and status. Thus it would make sense to see uneven distributions of certain trade goods, as mediated by the controlling groups. Some people were “in,” with access, and others may have been “out.”

Ethnohistoric records indicate cases of indigenous groups rejecting contact with Europeans and their goods. For example, Jesuit missionaries described an entire village no longer using French kettles because the foreigners and their goods were blamed for disease.

There are other reasons European goods do or do not show up in the archaeological record. How near or far a place was from transport routes, and local politics, both within and between groups, could play a role. Whether Europeans made direct contact, or there were only indirect links, could affect availability. Objects used and kept in settlements could also vary from those intentionally buried in cemeteries. Above all, the majority of sites are only partly investigated at best, some are as yet unknown. And sadly the archaeological record is affected by the looting and destruction of sites. Only a direct dating approach removes the Eurocentric and historical lens, allowing an independent time frame for sites and past narratives.

Effects of Re-dating Indigenous History

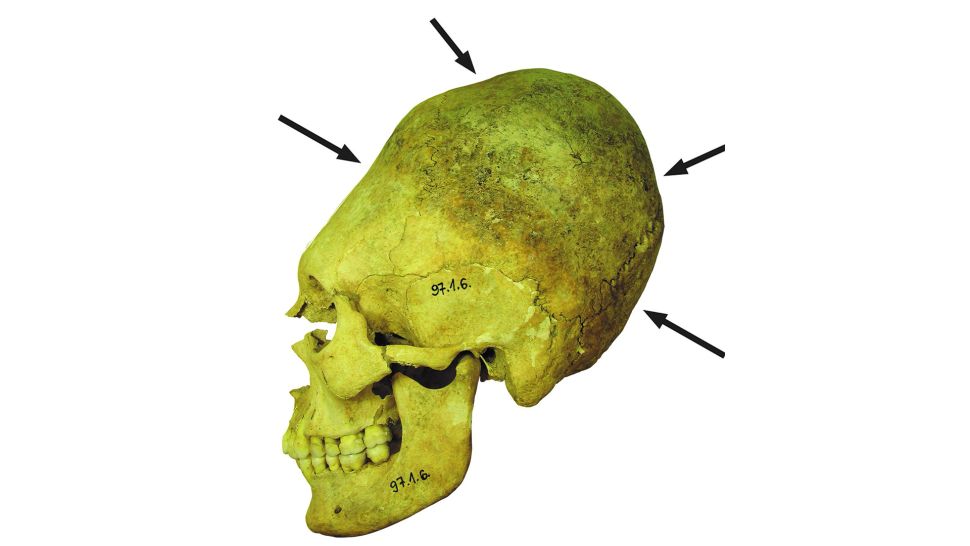

Apart from changing the dates for textbooks and museum displays, the re-dating of a number of Iroquoian sites raises major questions about the social, political and economic history of indigenous communities. For example, conventionally, researchers place the start of a shift to larger and fortified communities, and evidence of increased conflict, in the mid-15th century.

However, our radiocarbon dates find that some of the key sites are from a century later, dating from the mid-16th to start of the 17th centuries. The timing raises questions of whether and how early contacts with Europeans did or did not play a role. This period was also during the peak of what’s called the Little Ice Age, perhaps indicating the changes in indigenous settlements have some association with climate challenge.

Our new radiocarbon dates indicate the correct time frame; they pose, but do not answer, many other remaining questions.

Note: This article was originally published under the title ‘ Archaeologists have a lot of dates wrong for North American indigenous history – but we’re using new techniques to get it right’ by Sturt Manning on The Conversation.