Amazing 1,600-year-old biblical mosaics reveal a new perspective on Galilean life

In its eighth dig season, the vibrant mosaic flooring of a fifth-century synagogue excavated in the small ancient Galilee village of Huqoq continues to surprise. The 2018 Huqoq dig has uncovered unprecedented depictions of biblical stories, including the Israelite spies in Canaan. With its rich finds, the Byzantine-period synagogue busts scholars’ preconceived notions of a Jewish settlement in decline.

“What we found this year is extremely exciting,” the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Prof. Jodi Magness told The Times of Israel, saying the biblically-based depictions are “unparalleled” and not found in any other ancient synagogue.

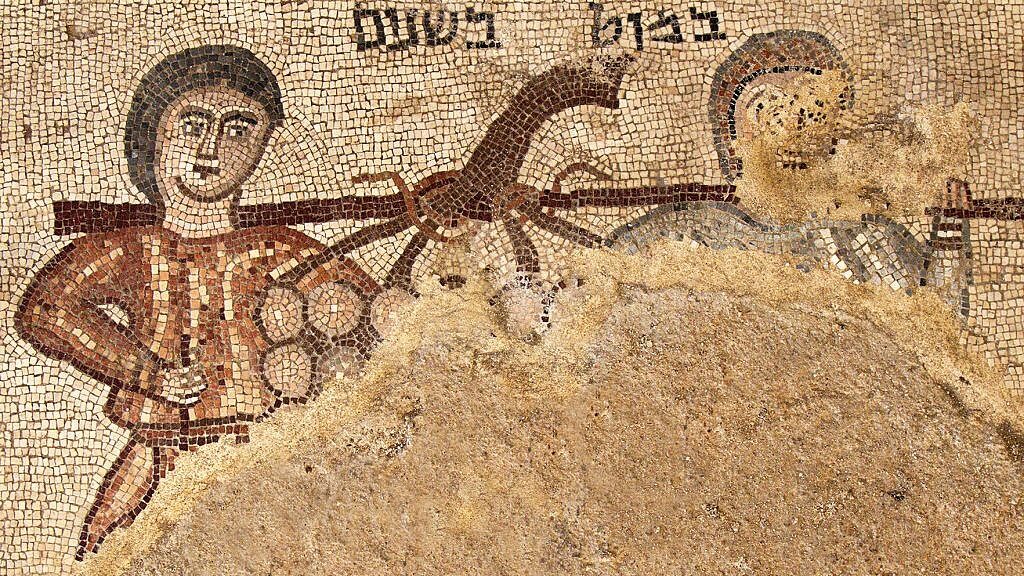

“The synagogue just keeps producing mosaics that there’s just nothing like and is enriching our understanding of the Judaism of the period,” said Magness. A recently unearthed mosaic shows two men carrying between them a pole on their shoulders from which is hung a massive cluster of grapes (the same as the easily recognizable symbol of Israel’s Ministry of Tourism). With a clear Hebrew inscription stating, “a pole between two,” it illustrates Numbers 13:23, in which Moses sends two scouts to explore Canaan.

Before wrapping up the dig season last week, the team of 20 excavators uncovered a further biblical mosaic panel, which shows a youth leading an animal on a rope and includes the inscription, “a small child shall lead them.” It is a reference to Isaiah 11:6, “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.”

According to a 2013 Biblical Archaeology Review article by Magness, “Huqoq was a prosperous village about 3 miles west of Magdala (home of Mary Magdalene) and Capernaum (where Jesus taught in the synagogue),” located next to a fresh spring. It appears twice in the Hebrew Bible, in Joshua 19:32–34 and 1 Chronicles 6:74–75. “Our excavations have not reached these early occupation levels, however,” she writes.

These two newly published mosaics join a pantheon of others — from 2012 and 2013, two Samson depictions, to fantastical elephants and mythical creatures from 2013-2015, Noah’s Ark in 2016, and colourful and as yet unpublished Jonah and the whale in 2017. During this year’s dig, the team also continued to expose and study rare 1,600-year-old columns, first uncovered in previous seasons, which are covered in painted plaster with red, orange, and yellow vegetal motifs. Other discovered columns, said Magness, were painted to imitate marble.

However, despite these “imitation marble” columns, this was no poor man’s synagogue. Much in the manner of King Herod decorating his palaces with painted faux-marble frescos, the columns and gorgeous mosaics point to a wealthy, flourishing fifth-century Jewish settlement, said, Magness.

“In general, unless you’re in a really important church in the Byzantine period, you won’t find marble, rather this common local alternative,” she said. She laughed, saying there is a feeling of “one-ups-manship” in the construction of the Huqoq synagogue.

“Every village has its own synagogue,” Magness said. “In Huqoq there’s a feeling that the villagers said, ‘We’re going to build the biggest and best.’ It’s as if they decided to throw everything into it.”

The obvious wealth and disposable income displayed in the synagogue is “contradicting a widespread view — not my view — that the Jewish community was in decline,” she said.

However, not only the synagogue was rich and diverse, but also the Judaism it housed.

“The mosaics decorating the floor of the Huqoq synagogue revolutionizes our understanding of Judaism in this period,” said Magness in a press release. “Ancient Jewish art is often thought to be aniconic, or lacking images. But these mosaics, colourful and filled with figured scenes, attest to a rich visual culture as well as to the dynamism and diversity of Judaism in the Late Roman and Byzantine periods.”

According to Magness, “Rabbinic sources indicate that Huqoq flourished during the Late Roman and Byzantine periods (fourth–sixth centuries CE). The village is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud in connection with the cultivation of the mustard plant.”

Aside from the outstanding mosaics and colourfully painted columns, there are other features of note in this synagogue: Discovered in 2012, an inscription flanked by the faces of two women and a man (a fourth face, presumably of a man, is not preserved) might be the first donor portraits found in a Jewish house of prayer. The practice, said Magness, was “not uncommon in Byzantine churches,” but has no parallel example found in a synagogue of the era. Although there are aspects of the synagogue that may point to a Christian influence, for example, the possible donor portraits, Magness does not believe the Huqoq community was more impacted than other neighbouring congregations.

“In general there was some interaction between Jews and Christians, as well as Judaism and Christianity, in the sense that both religions laid claim to the same tradition and called themselves the ‘true Israel,’” said Magness. It is not coincidental that the same biblical themes appear in both forums.

“They are clearly some sort of dialogue, broadly speaking… A lot of what we see at Huqoq can be understood on the background of the rise of Christianity,” she said.

“There is evidence of occupation at the site during the Persian, Hellenistic, Early Roman, Abbasid, Fatimid and Crusader-Mamluke periods. The modern village was abandoned in 1948 during the fighting in Israel’s War of Independence. In the 1960s, the site was bulldozed,” writes Magness in BAR. It appears that the Huqoq synagogue is the ancestor of what seems to be a later, 12-13th century Jewish house of prayer. Faint, broken remnants of that incarnation’s mosaic flooring have also been discovered a meter above the dynamic mosaics of the Byzantine era.

It is possible, said Magness, that this is a synagogue mentioned by French 14th century Jewish physician-turned-traveller Isaac HaKohen Ben Moses, aka Ishtori Haparchi, mentioned in his 1322 geography of the Holy Land, “Sefer Kaftor Vaferach.”

Regardless, there are no extant medieval synagogues in Israel today, making this find potentially no less important than the more attention-grabbing images in the fifth-century mosaic floors, said Magness.

Both of these finds — the medieval synagogue and beautiful Byzantine mosaics — are all the more remarkable in that they are a by-product of a different scholarly quest: Magness decided to excavate at Huqoq to test a wide-spread Galilean synagogue dating system, which dated the buildings based on their architectural structures.

“Since the early 20th century, when these synagogues began coming to light, scholars developed a tripartite chronology: The earliest, these so-called ‘Galilean-type synagogues,’ were dated to the second and third centuries CE, followed by ‘transitional synagogues’ in the fourth century, and then by ‘Byzantine synagogues’ in the fifth and sixth centuries,” writes Magness in the BAR article. Although housed in a fifth-century village, based on its architectural features, according to previous scholarly consensus, the Huqoq synagogue should have been classified a “Galilean-type synagogue” and dated to the second or third centuries. This is, Magness has proven, clearly not the case.

What was originally to have been a brief excavation has turned into eight seasons. And although Magness is assisted by Shua Kisilevitz of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and Tel Aviv University, the excavation is funded independently of the IAA, by sponsors including UNC-Chapel Hill, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, the Friends of Heritage Preservation, the National Geographic Society, the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust, and the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies. There will be a 2019 dig season, said Magness, who estimated she needs at least another four years to complete the ever-evolving project.

“Every year, there is another mind-blowing, weird discovery,” said Magness.