Cache of Roman Coins Found in Eastern England

The largest haul of Roman coins from the early 4th Century AD ever found in Britain has been unearthed near Sleaford by 2 metal detector enthusiasts.

The discovery was made near Rauceby village after years of painfully searching the area by the detectors.

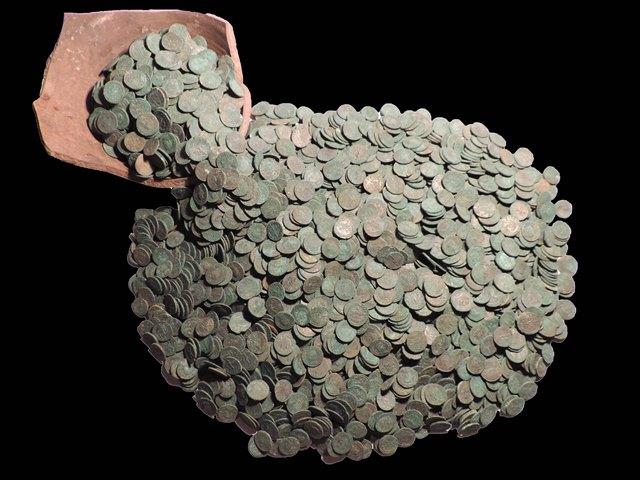

The hoard, which consists of more than 3,000 copper alloy coins, many of which are historically unique, is now being considered by the British Museum and is considered to be of major international importance.

The coins have today (Friday) officially been declared treasure under the Treasure Act 1996 at Lincoln Coroner’s Court. Finder Rob Jones, a 59 year old engineering teacher from Lincoln, and his friend Craig Paul, a 32 year old planner from Woodhall Spa, were speechless when they made the discovery in July 2017.

Rob said: “Our metal detectors started making signal noises, prompting us to dig down and have a look.” “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I’ve found a few things before, but absolutely nothing on this scale. I was totally amazed.

Finding the coins was the ultimate experience that we will never forget.”It’s an incredibly humbling experience knowing that when you discover something like this, the last time someone touched it was nearly 2,000 years ago! I was completely flabbergasted!

“A full investigation of the site was then undertaken by Craig, Dr Adam Daubney, archaeologist at Lincolnshire County Council and Sam Bromage from the University of Sheffield. During the excavation another hoard of 10 coins was found.

Craig commented: “It was fantastic to join the excavation to see Adam and Sam in action. To be there and see the pot appear out of the ground was really something. I never expected that there would be a second smaller hoard – that was just a bonus and really got us asking questions!”Dr Daubney said: “The coins were found in a ceramic pot, which was buried in the centre of a large oval pit – lined with quarried limestone.

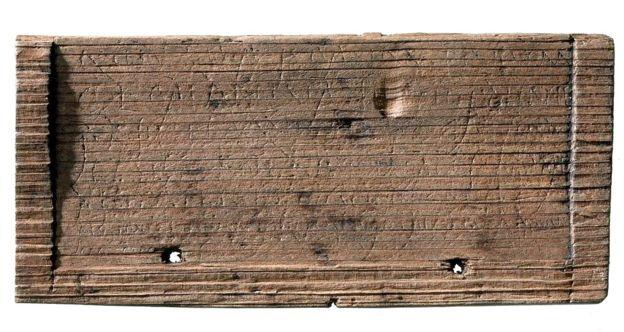

What we found during the excavation suggests to me that the hoard was not put in the ground in secret, but rather was perhaps a ceremonial or votive offering. The Rauceby hoard is giving us further evidence for so-called ‘ritual’ hoarding in Roman Britain.”

Dr Eleanor Ghey, Curator of Iron Age and Roman Coin Hoards at the British Museum, added: “At the time of the burial of the hoard around AD 307, the Roman Empire was increasingly decentralised and Britain was once again in the spotlight following the death of the emperor Constantius in York.

Roman coins had begun to be minted in London for the first time. As the largest fully recorded find of this date from Britain, it has great importance for the study of this coinage and the archaeology of Lincolnshire.”

Paul Cope-Faulkner Archaeology Senior Manager at Heritage Lincolnshire added: “It is an exciting discovery and furthers our understanding of how important the area around Sleaford was in the closing days of the Roman empire.

Although we may never know why such a huge number of coins were collected together, it is possible that they were some form of offering to a temple, as many of the coins were not overly valuable in themselves.”I must also congratulate the two detectorists for reporting the hoard and allowing archaeologists to examine it so that the story of Roman Rauceby and Sleaford can be told.”