Ancient Babylonian tablet reveals that Noah’s ark was rounded in shape

Irving Finkel is the curator from central casting. Battered clothes, bushy white beard, little circular glasses, boundless enthusiasm. From a distance, he looks about 100, but as he sprints across the British Museum’s Great Court to offer the warmest of handshakes – he is 10 minutes late for our meeting – you realise he is much younger.

In reality, he is 62 going on 12, since a lifetime spent examining the clay tablets of ancient Mesopotamia has left him seemingly unaffected by the cares of the workaday world.

“The man who is tired of tablets is tired of life,” he announces in his delightful new book, The Ark Before Noah, which sets out to demonstrate that the biblical flood narrative was derived from stories that had been embedded in Sumerian and Babylonian society and literature for thousands of years.

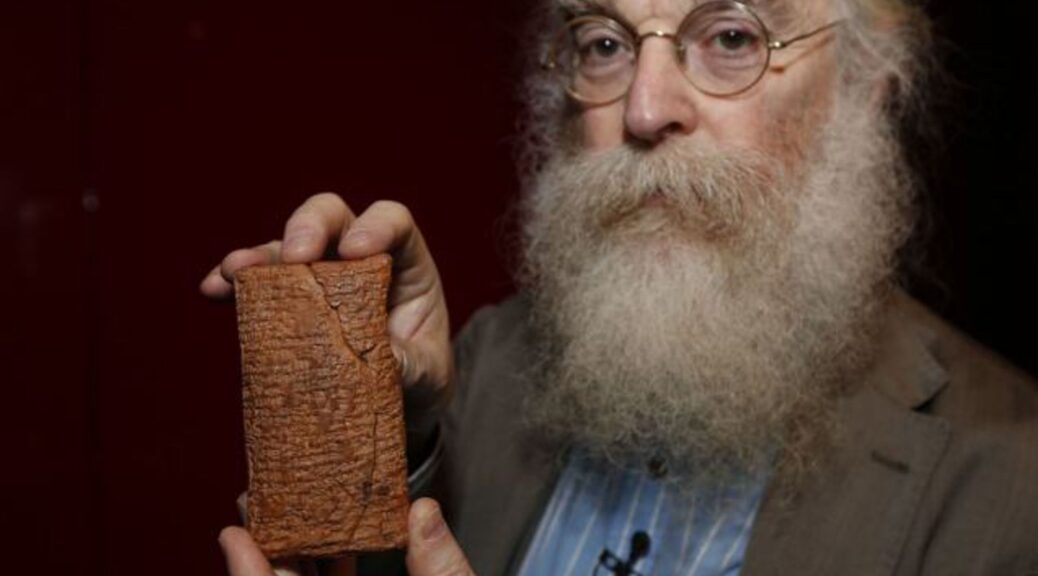

The book revolves around a clay tablet dating from about 1800BC with 60 lines of cuneiform (the tiny, wedge-shaped script on the tablets), which relate to part of the flood story. Finkel first encountered this “Ark tablet” almost 30 years ago when a member of the public brought it to show him.

He has spent the past 20 years translating the text and putting it in the context of other flood literature and is now ready to unveil it to the world. This is in the form of his book and a Channel 4 documentary, due to be shown in August, which is building the ark to the specifications on Finkel’s tablet to see if it floats.

Finkel’s bombshell – and the point of the Channel 4 programme – is that he reckons the original ark was round. “The fact that the ark was round is the headline finding,” he says. “It’s something nobody in the world had anticipated because everybody knows what Noah’s ark looked like.” All those pictures of oblong, multi-decked boats that look like neat country cottages will have to be redrawn.

The mobile phone-sized ark tablet is housed in a posh-looking red box with “Instructions on the Building of the Ark” written on it. Finkel takes the tablet out of the box and lets me hold it – a chance to commune with the ghosts of ancient Mesopotamia. I manage not to drop it. As well as casting new light on the shape of the original ark, it also contains the first written allusion to the animals “going in two by two”. In the book, he describes unearthing this reference on the broken, weathered tablet with its worn-out wedges as his “biggest shock in 44 years of grappling with difficult lines in cuneiform tablets … I nearly fell off my chair.” He is good at conveying the excitement of academic discoveries, a television natural.

He could have written up his findings in an academic tome that would have pleased his peers, but he has instead produced a digressive, amusing, personal book for the general reader, a book that is willing to ask big questions – such as how did the Babylonian ark story find its way into the Bible? – and make the odd educated guess.

“There’s very little in existence that helps people with this subject. Mostly we’re orientated to make it seem forbidding and difficult.”

The first draft was written in what he calls a “very defensive” way. “In the world of scholarship,” he says, “you don’t make a statement without supporting it with footnotes and references to German periodicals.”

“When I first wrote the book I did it feeling that all my colleagues were going to read it and they’d be saying [puts on whispery academic voice] ‘I rather doubt …’ But when I wrote the second draft, I suddenly had this brilliant idea that I would forget my colleagues existed and write for everybody else, which was very liberating. It meant I could speak with my real voice.” In the book, Finkel explains his own route into Assyriology and his continuing love affair with the subject. He had wanted to be a curator at the British Museum from the age of nine and was overjoyed when he joined in 1979. But how will those colleagues react? “I don’t know,” he admits. “They’ll probably all gang up against me at conferences and throw fruit.”

Finkel wears several academic hats. As well as being in charge of the museum’s 130,000 clay tablets, he looks after its collection of board games and has made it a personal crusade to preserve old diaries, launching the Great Diary Project to “provide a permanent home for unwanted diaries of any date or kind”.

What links Mesopotamian inscriptions and the humdrum diaries of elderly ladies from Carshalton? “I had this sudden epiphany that diaries were like clay tablets,” he says. In 4,000 years time, the shopping lists of elderly ladies in Surrey will be pored over with fascination.

Finkel sees his mission as rescuing artefacts of the past – clay tablets, obscure Indian board games, the diaries of ordinary people – before they are swept away, a latter-day Noah constructing a cultural ark. A round one of course.