Archaeologists discover almost complete 300,000-year-old elephant skeleton

Archaeologists have discovered the nearly complete skeleton of an enormous, now-extinct elephant that lived about 300,000 years ago in what is now the northern German town of Schöningen, according to new research.

Although this elephant — the Eurasian straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) — likely died of old age, meat-eaters promptly devoured it; bite marks on its bones suggest that carnivores feasted on the dead beast, and flint flakes and bone tools found near the elephant indicate that humans scavenged whatever was left, the researchers said.

“The Stone Age hunters probably cut meat, tendons, and fat from the carcass,” project researcher Jordi Serangeli, head of the excavation in Schöningen, said in a statement.

The elephant died on the western side of a vast lake, a hint that it perished from natural causes.

“Elephants often remain near and in water when they are sick or old,” Ivo Verheijen, a doctoral student in archaeozoology and paleontology at the University of Tübingen, said in the statement. In addition, the elephant, a female, had worn teeth, suggesting it was old when it died, he said.

Image Gallery

Researchers have found the remains of at least 10 elephants dating to the Lower Paleolithic — also known as the Old Stone Age (about 3 million to 300,000 years ago) — over the past several years at Schöningen. But this new find is by far the most complete. The remains include 7.5-foot-long (2.3 meters) tusks — which are 125% longer than the average 6-foot-long (1.8 m) tusk of a modern African elephant, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

The researchers also found the complete lower jaw, numerous vertebrae and ribs, large bones from three of its four legs, and all five of its delicate hyoid bones, which are found in the neck and help support the tongue and voice box.

This P. antiquus elephant had a shoulder height of about 10.5 feet (3.2 m) and would have weighed about 7.5 tons (6.8 metric tons). “It was therefore larger than today’s African elephant cows,” Verheijen said.

Near these remains, researchers found 30 small flint flakes and two long bone tools. Micro flakes embedded in these two bones suggest the ancient humans who scavenged the elephant used them to sharpen stone tools (called knapping) at the site, said project researcher Bárbara Rodríguez Álvarez, an archaeologist at the University of Tübingen.

Of note, the ancient humans who likely scavenged the elephant were not Homo sapiens. The earliest evidence of H. sapiens in Europe dates to about 45,000 years ago, according to excavations at a cave in Bulgaria, a study published last week in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution found. Instead, these human scavengers were likely H. heidelbergensis, an extinct human relative who lived about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, the researchers in Germany said.

Wildlife watering hole

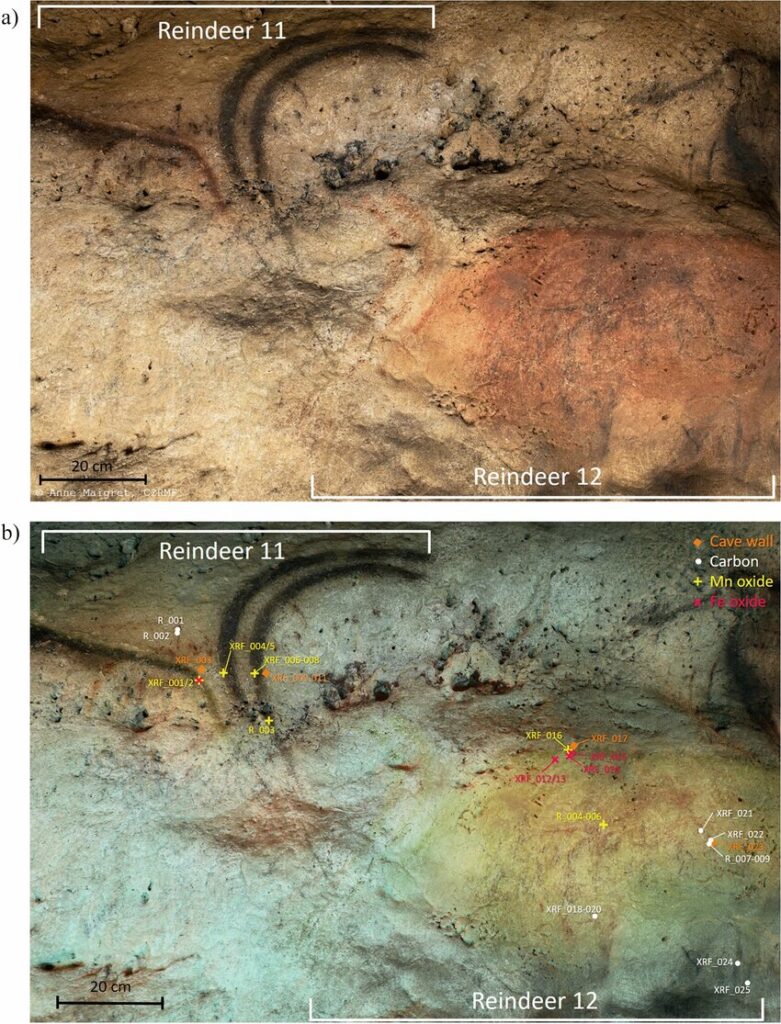

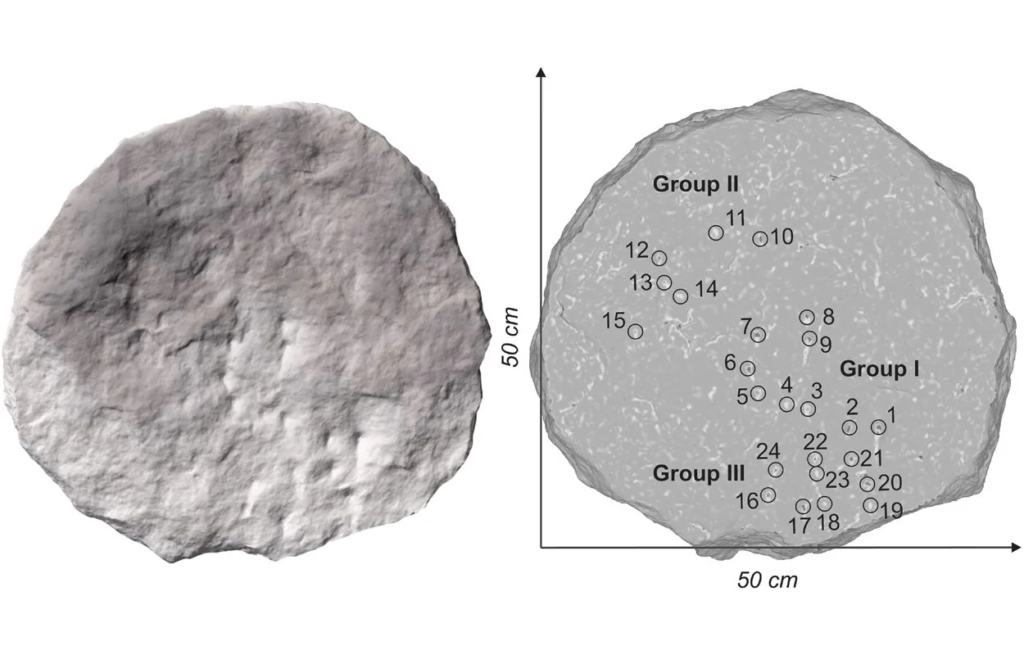

The lake was a popular hole for elephants, according to several of their preserved footprints just 330 feet (100 m) from the new elephant excavation site.

“A small herd of adults and younger animals must have passed through,” Flavio Altamura, a researcher at the Department of Antiquities at Sapienza University in Rome, said in the statement. “The heavy animals were walking parallel to the lakeshore. Their feet sank into the mud, leaving behind circular tracks.”

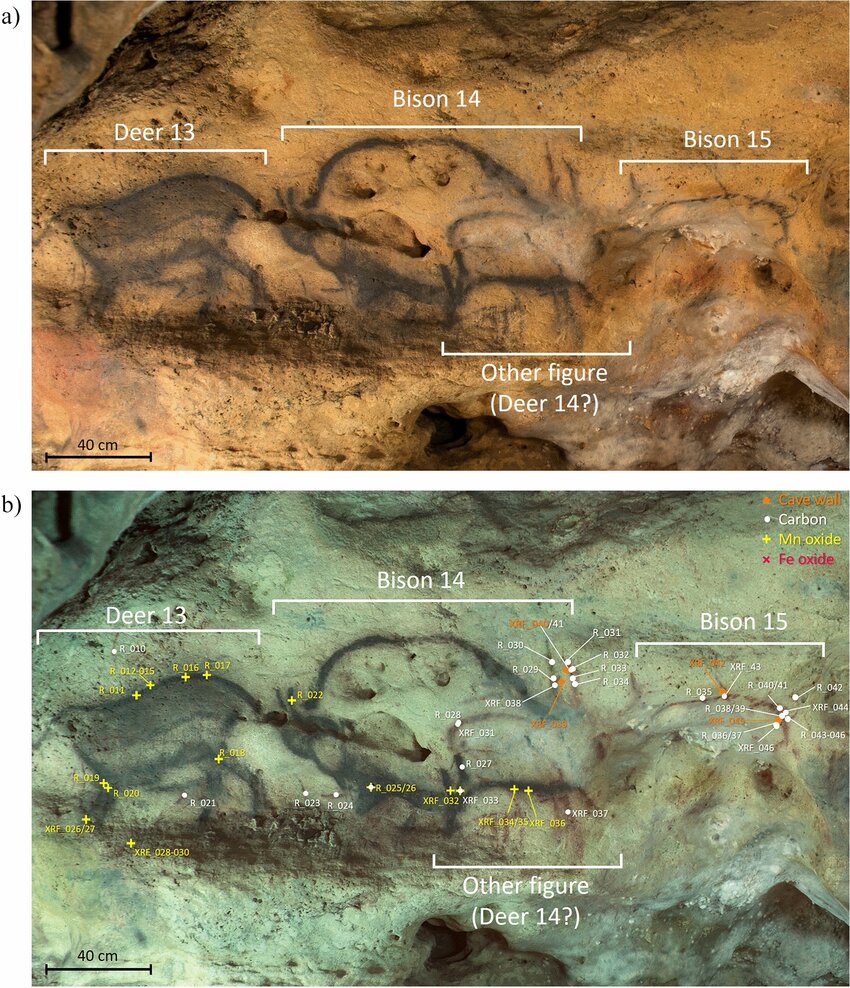

These elephants would have lived in a comfortable climate, comparable to today’s; about 300,000 years ago, Europe was in the Reinsdorf interglacial, a warmer period bookended by two glacial (or colder) periods. Other animals thrived there, too. About 20 kinds of large animals lived around the lake, including lions, bears, saber-toothed cats, rhinoceroses, wild horses, deer, and large cattle, according to excavations. “The wealth of wildlife was similar to that of modern Africa,” Serangeli said.

All of these animals attracted ancient human hunters. Archaeologists have found the remains of 10 wooden spears and one throwing stick from 300,000 years ago, according to a study published online on April 20 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The new finding was uncovered in a collaborative effort between the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen in Germany and the Lower Saxony State Office for Heritage. The research will be published in the magazine “Archäologie in Deutschland” (Archaeology in Germany) and was presented at a press conference in Schöningen on May 19.