Timbers of Fifteenth-Century Newport Ship Analyzed

Tree-ring analysis has been able to date a medieval ship found in a Welsh riverbank within a few months. The wreck of a 15th Century ship was found in the mud of Newport’s River Usk in 2002 and experts believe it is as significant a find as the Mary Rose.

Now researchers have found timbers from the hull of the former wine-trading vessel were made from oak trees that were felled in the winter of 1457-58.

“It helps us refine when the ship was built,” said ship curator Toby Jones.

It is another major development for the Newport ship conservation project who have been working for more than 20 years to conserve and ultimately rebuild the vessel, which is a century older than the Mary Rose.

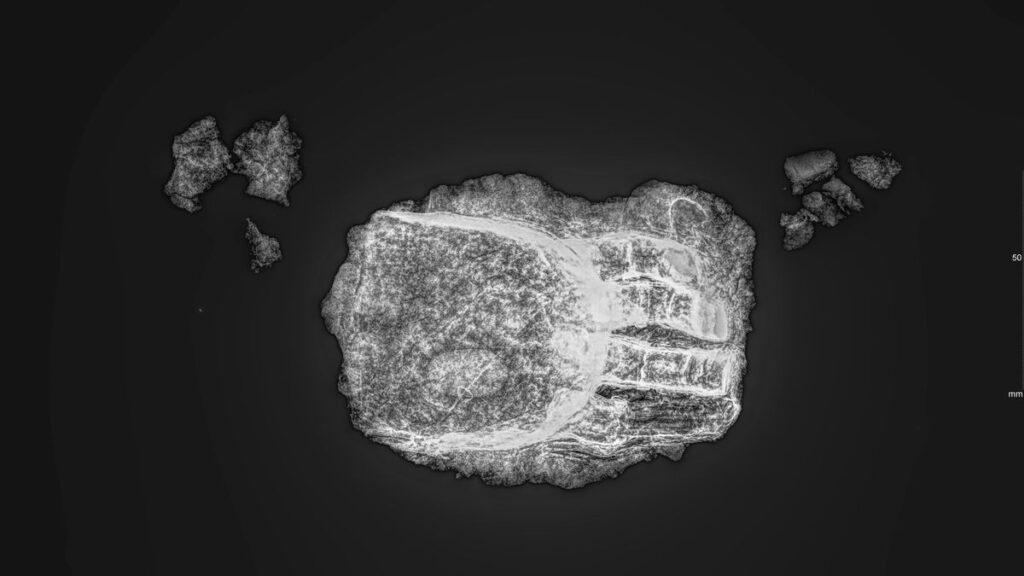

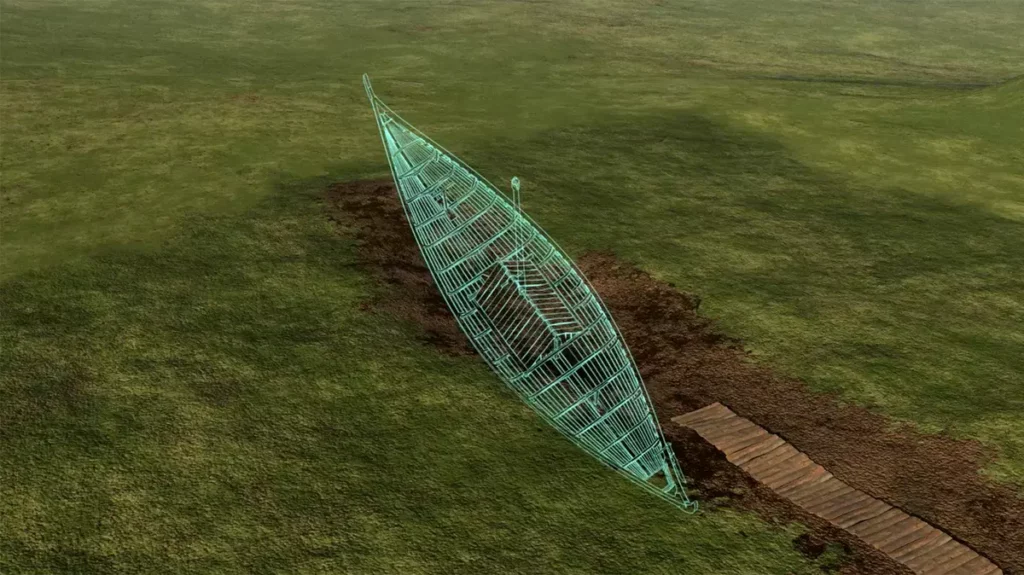

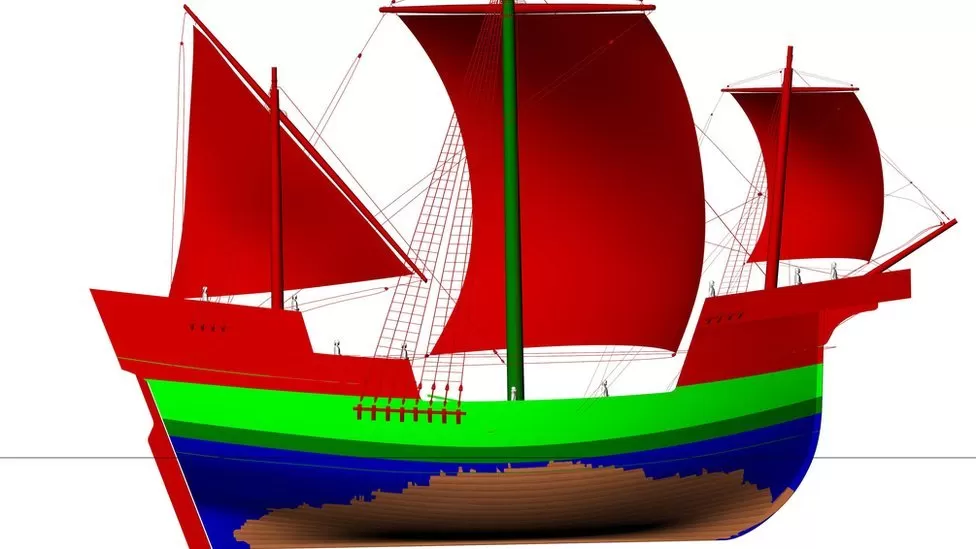

Earlier this year, the team working on the £8m project finished the conservation process of the 2,500 pieces of wood uncovered in the banks of the River Usk by workers building Newport’s Riverfront Theatre. Experts believe the 30m (98ft), 400 tonne, medium-sized boat was having a refit in Newport in 1468 or 1469 following a voyage from the Iberian Peninsula to Bristol when its moorings broke.

After collapsing into an inlet of the River Usk, its 25-tonne hull was found more than 550 years later preserved in a wet, muddy riverbank.

Archaeologists are planning the world’s largest attempt to put an archaeological ship back together which historians have called the the world’s largest 3D puzzle.

TV historian Dan Snow has said the Newport ship was “one of the most interesting and important shipwrecks found in British waters in a generation” and was of “global significance and interest”.

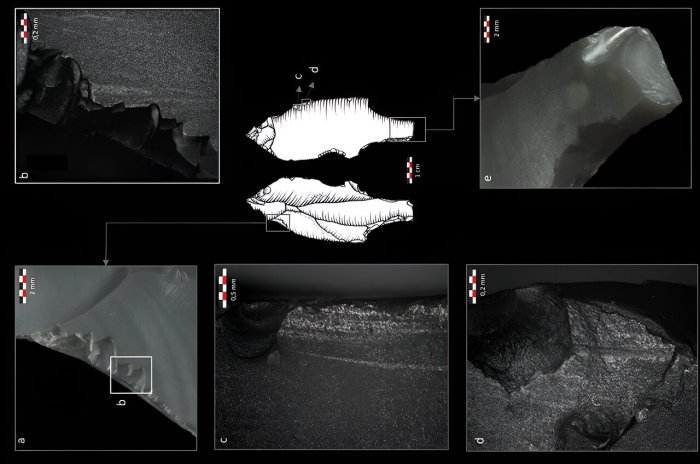

In another breakthrough, experts now know when the ship was built using oxygen isotope dendrochronology – an advanced study of tree-ring data – to determine an estimated date when it was built.

“We do know it came into Newport in 1468 or 1469 but we now know the ship was in existence for not quite a decade,” added Dr Jones.

“It allows us to really focus on that 1457-58 period for historical research but it shows this type of analysis has real potential to refine various parts of the construction sequence of the Newport ship.”

Research by University of Wales Trinity Saint David and Swansea University suggests the vessel was constructed soon after the oak trees were chopped down in the winter of 1457-58.

The research, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, also suggested the vessel had a working life of about 10 years before coming to Newport for repairs in the late 1460s.

Previous research has shown that the ship timbers originated from forests in the Basque Country in northern Spain and that the ship was likely built along the Basque coast.

Tudor king Henry VIII’s flagship naval vessel the Mary Rose is perhaps the most famous 16th Century ship on display while the Vasa in Sweden is the 17th Century equivalent.

Now historians say the Newport ship could become the only 15th Century maritime exhibit on show anywhere in the world when it is restored. Historians have undertaken painstaking 20-year conservation work including drying out, freeze drying treating the oak timbers before beginning to focus on rebuilding.

Archaeologists had thought the ship may been 10 years older than the new analysis proves – and the research may possibly help experts rebuild the vessel.

“It allows us to focus our resources on that specific season,” said Dr Jones.

“We can cut out anything from early 1450s now so narrow it down to a smaller window we can be more effective in our research to identify the ship.

“We can start to do this analysis on many of the timbers and if it gets really precise, we can start to determine the construction sequence and what timbers were harvested when and when they were added to the ship – so we can put dates on every timber.”

Dr Jones said the pioneering dating of the Newport ship was “stunning” because of what the wood has been through.

“The Newport ship has been through a lot,” he said. “More than 500 years underground, gone through cleaning, conservation, soaked in wax and freeze-dried – and yet these isotope signatures are still in the timbers.

“I wouldn’t have thought that was possible but this analysis has proved that information is still locked away in those tree rings.

“It’s great for us, it’s great for the Newport ship but also means we can do it on other vessels and timber structures that previously didn’t date with traditional ring dendrochronology can now potentially be dated with oxygen isotope or stable isotope dendrochronology.

“It’s really exciting, not just for ships and ship archaeology but for anything made of wood that’s old.”

Experts used oxygen isotope dendrochronology to estimate when the timbers were harvested which has been called a “revolutionary” development in dating wood, like the advent of DNA technology in criminology.

“This process is only five to 10 years old and allows us to find answers today that we couldn’t get before,” said Prof Nigel Nayling, University of Wales Trinity St David’s chair of archaeology.

“It’s a complex process that takes a long time, days and days of work, and a lot of resource but it is a game-changer for archaeologists, it’s a significant innovation.”