Celtic woman found buried inside a TREE ‘wearing fancy clothes and jewellery’ after 2,200 years

It’s believed the woman, who died 2,200 years ago, commanded great respect in her tribe, as she was buried in fine clothes and jewellery.

Scientists say the woman was Celtic. The Iron Age Celts are known to have buried members of their tribe in “tree coffins” buried deep underground.

The woman’s remains were found in the city of Zurich in 2017, according to Live Science.

Bedecked in a fine woolen dress and shawl, sheepskin coat, and a necklace made of glass and amber beads, researchers believe she performed little if any hard labor while she was alive. It’s estimated she was around 40 years old when she died, with an analysis of her teeth indicating a substantial sweet tooth.

Adorned in bronze bracelets and a bronze belt chain with iron clasps and pendants, this woman was not part of low social strata. Analysis of her bones showed she grew up in what is now modern-day Zurich, likely in the Limmat Valley.

Most impressive, besides her garments and accessories, is the hollowed-out tree trunk so ingeniously fixed into a coffin. It still had the exterior bark intact when construction workers stumbled upon it, according to the initial 2017 statement from Zurich’s Office of Urban Development.

While all of the immediate evidence — an Iron Age Celtic woman’s remains, her bewildering accessories, and clothing, the highly creative coffin — is highly interesting on its own, researchers have discovered a lot more to delve into since 2017.

According to The Smithsonian, the site of discovery has been considered an archaeologically important place for quite some time. Most of the previous finds here, however, only date back as far as the 6th century A.D.

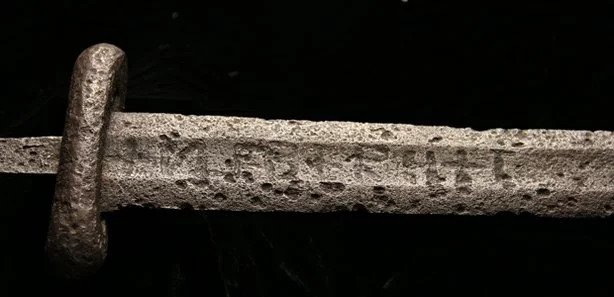

The only exception seems to have occurred when construction workers found the grave of a Celtic man in 1903. They were in the process of building the school complex’s gym, the Office of Urban Development said when they discovered the man’s remains buried alongside a sword, shield, and lance.

Researchers are now strongly considering that, because the Celtic woman’s remains were found a mere 260 feet from the man’s burial place, they probably knew each other.

Experts have claimed that both figures were buried in the same decade, an assertion that the Office of Urban Development said it was “quite possible.”

Though archaeologists previously found evidence that a Celtic settlement dating to the 1st century B.C. lived nearby, researchers are rather confident that the man found in 1903 and the woman found in 2017 belonged to a smaller, separate community that has yet to be entirely discovered.

The department’s 2017 press release stated that researchers would initiate a thorough assessment of the grave and its contents, and by all accounts, they’ve done just that.

Archaeologists salvaged and conserved any relevant items and materials, exhaustively documented their research, and conducted both physical and isotope-based examinations on the woman.

Most impressive to experts was the woman’s necklace, which had rather impressive clasps on either end.

The office said that its concluded assessment “draws a fairly accurate picture of the deceased” and the community in which she lived. The isotope analysis confirmed that she was buried in the same area she grew up in.

While the Celts are usually thought of as being indigenous to the British Isles, they lived in many different parts of Europe for hundreds of years. Several clans settled in Austria and Switzerland, as well as other regions north of the Roman Empire.

Interestingly enough, from 450 B.C. to 58 B.C. — the exact same timeframe that the Celtic woman and man were buried — a “wine-guzzling, gold-designing, poly/bisexual, naked-warrior-battling culture” called La Tène flourished in Switzerland’s Lac de Neuchâtel region.

That is until Julius Caesar launched an invasion of the area and began his conquest of western and northern Europe. Ultimately, it seems the Celtic woman received a rather kind and caring burial and left Earth with her most treasured belongings by her side.