The Oldest City in The Americas Is an Archeological Wonder, And It’s Under Invasion

The oldest archaeological site in the Americas, having survived for 5,000 years, is under threat from squatters that claim that the coronavirus pandemic has left them with no other option but to occupy the sacred city.

The government wants to take all of the items found from archaeological sites for national security. Because of this, Ruth Shady, who archives the items before, and after she is done, she has been threatened with death.

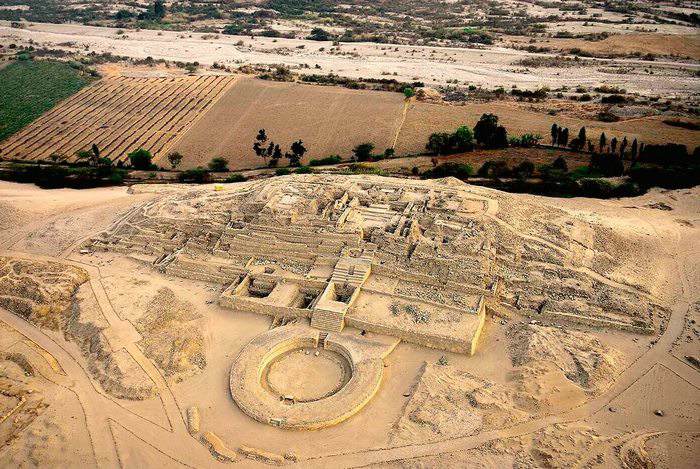

Archaeologists told an AFP team visiting Caral that squatter invasions and destruction began in March when the pandemic forced a nationwide lockdown.

“There are people who come and invade this site, which is state property, and they use it to plant,” archaeologist Daniel Mayta told AFP.

“It’s hugely harmful because they’re destroying 5,000-year-old cultural evidence.”

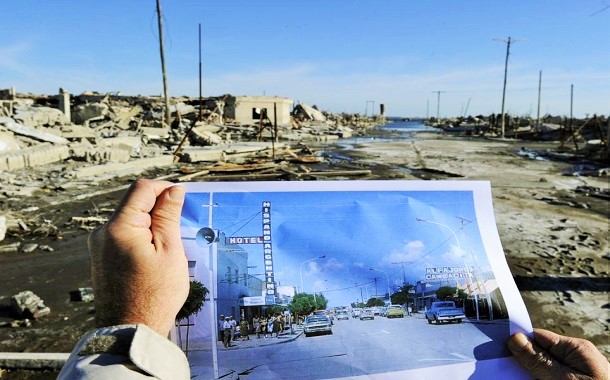

Caral is situated in the valley of the Supe river some 182 kilometres (110 miles) north of the capital Lima and 20km from the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Developed between 3,000 and 1,800 BCE in an arid desert, Caral is the cradle of civilization in the Americas. Its people were contemporaries of Pharaonic Egypt and the great Mesopotamian civilizations. It pre-dates the far better known Inca empire by 45 centuries.

None of that mattered to the squatters, though, who took advantage of the minimal police surveillance during 107 days of lockdown to take over 10 hectares of the Chupacigarro archaeological site and plant avocados, fruit trees, and lima beans.

“The families don’t want to leave,” said Mayta, 36.

“We explained to them that this site is a (UNESCO) World Heritage site and what they’re doing is serious and could see them go to jail.”

Death threats

Shady is the director of the Caral archaeological zone and has been managing the investigations since 1996 when excavations began. She says that land traffickers – who occupy state or protected land illegally to sell it for private gain – are behind the invasions.

“We’re receiving threats from people who are taking advantage of the pandemic conditions to occupy archaeological sites and invade them to establish huts and till the land with machinery … they destroy everything they come across,” said Shady.

“One day they called the lawyer who works with us and told him they were going to kill him with me and bury us five meters underground” if the archaeological work continued at the site.

Shady, 74, has spent the last quarter of a century in Caral trying to bring back to life the social history and legacy of the civilization, such as how the construction techniques they used resisted earthquakes.

“These structures up to five thousand years old have remained stable up to the present and structural engineers from Peru and Japan will apply that technology,” said Shady.

The Caral inhabitants understood that they lived in the seismic territory. Their structures had baskets filled with stones at the base that cushioned the movement of the ground and prevented the construction from collapsing. The threats have forced Shady to live in Lima under protection. She was given the Order of Merit by the government last week for services to the nation.

“We’re doing what we can to ensure that neither your health nor your life is at risk due to the effects of the threats you’re receiving,” Peru’s President Francisco Sagasti told her at the ceremony.

Police arrests

Caral was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2009. It spans 66 hectares and is dominated by seven stone pyramids that appear to light up when the sun’s rays fall on them. The civilization is believed to have been peaceful and used neither weapons nor ramparts.

Closed due to the pandemic, Caral reopened to tourists in October and costs just US$3 to visit. During the lockdown, several archaeological pieces were looted in the area and in July police arrested two people for partially destroying a site containing mummies and ceramics.