Unlocking 2,000-year-old Herculaneum scrolls were buried when Mount Vesuvius erupted.

Artefacts from the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, buried in ash during an explosive Mount Vesuvius eruption, was a scale-out at the British Museum in 2013. But could even bigger treasures still lie underground, including lost classical literature?

Scholars have been investigating the lost works of ancient Greek and Latin literature for centuries. Books were found in monastic libraries in the Renaissance. Papyrus scrolls were discovered in Egypt’s deserts in the late 19th century. But only in Herculaneum in southern Italy has an entire library from the ancient Mediterranean been discovered in situ.

On the eve of the catastrophe in AD 79, Herculaneum was a chic resort city on the Bay of Naples, and during the hot Italian summer many top families went out to relax and recover. It was also an area where Rome’s richest people were involved with cultural uniqueness-none no other than Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a politician and Julius Caesar’s father–in–law.

In Herculaneum, Piso built a palatial seaside villa, its wide façade exceeding 220 m (721 ft) alone. When excavated in the middle of the 18th century, there are more than 80 high-quality bronze and marble statues, including one of the Pan with a goat. When he came to plan his own exercise in cultural showing off, J Paul Getty chose to copy Piso’s villa for his own Getty museum in Malibu, California.

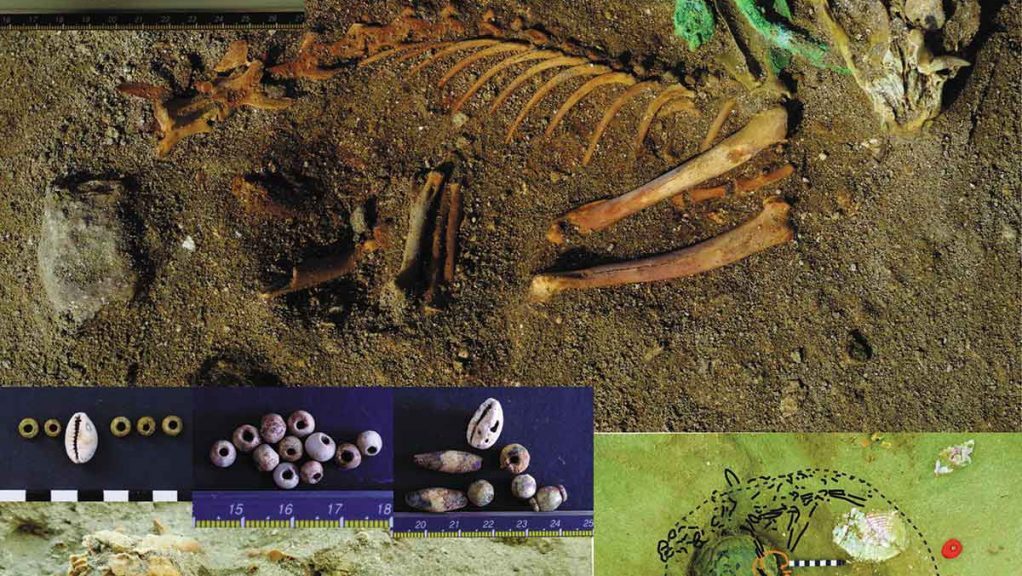

Piso’s grand villa, which has come to be known as the Villa of the Papyri, also contains the only library to have survived from the classical world. It is a relatively small collection, some 2,000 scrolls, which the eruption nearly destroyed and yet preserved at the same time.

A blast of furnace-like gas from the volcano at 400C (752F) carbonised the papyrus scrolls before the town was buried in fine volcanic ash which later cooled and solidified into rock. When excavators and treasure hunters set about exploring the villa in the 18th Century, they mistook the scrolls for lumps of charcoal and burnt logs. Some were used as torches or thrown onto the fire.

But once it was realised what they were – possibly because of the umbilicus, the stick at the centre of the scrolls – the challenge was to find a way to open them. Some scrolls were simply hacked apart with a butcher’s knife – with predictable and lamentable results. Later a conservator from the Vatican, Father Antonio Piaggio (1713-1796), devised a machine to delicately open the scrolls. But it was slow work – the first one took around four years to unroll. And the scrolls tended to go to pieces.

The fragments pulled off by Piaggio’s machine were fragile and hard to read. “They are as black as burnt newspaper,” says Dirk Obbink, a lecturer in Papyrology at Oxford University, who has been working on the Herculaneum papyri since 1983. Under normal light the charred paper looks “a shiny black” says Obbink, while “the ink is a dull black and sort of iridesces”.

Reading it is “not very pleasant”, he adds. In fact, when Obbink first began working on them in the 1980s the difficulty of the fragments was a shock. On some pieces, the eye can make out nothing. On others, by working with microscopes and continually moving the fragments to catch the light in different ways, some few letters can be made out. Meanwhile, the fragments fall apart. “At the end of the day, there would be black dust on the table – the black dust of the scroll powdering away. I didn’t even want to breathe.”

This all began to change 15 years ago.

In 1999, scientists from Brigham Young University in the US examined the papyrus using infrared light. Deep in the infrared range, at a wavelength of 700-900 nanometres, it was possible to achieve a good contrast between the paper and the ink. Letters began to jump out of the ancient papyrus. Instead of black ink on black paper, it was now possible to see black lines on a pale grey background.

Scholars’ ability to reassemble the texts improved massively. “Most of our previous readings were wrong,” says Obbink. “We could not believe our eyes. We were ‘blinded’ by the real readings. The text wasn’t what we thought it was and now it made sense.”

In 2008, a further advance was made through multi-spectral imaging. Instead of taking a single (“monospectral”) image of a fragment of papyrus under infrared light (at typically 800 nanometres) the new technology takes 16 different images of each fragment at different light levels and then creates a composite image.

With this technique, Obbink is seeking not only to clarify the older infrared images but also to look again at fragments that previously defied all attempts to read them. The detail of the new images is so good that the handwriting on the different fragments can be easily compared, which should help reconstruct the lost texts out of the various orphan fragments. “The whole thing needs to be redone,” says Obbink.

So what has been found? Lost poems by Sappho, the 100-plus lost plays of Sophocles, the lost dialogues of Aristotle? Not quite.

Despite being found in Italy, most of the recovered material is in Greek. Perhaps the major discovery is a third of On Nature, a previously lost work by the philosopher Epicurus.

But many of the texts that have emerged so far are written by a follower of Epicurus, the philosopher and poet Philodemus of Gadara (c.110-c.40/35BC). In fact, so many of his works are present, and in duplicate copies, that David Sider, a classics professor at New York University, believes that what has been found so far was in fact Philodemus’s own working library. Piso was Philodemus’s patron.

READ ALSO: THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS CONTAIN GENETIC CLUES TO THEIR ORIGINS

Not all of the villa’s scrolls have been unrolled through – and because of the damage, they suffer in the unwinding process that work has now been halted. Might it be possible to read them by unrolling them not physically, but virtually?

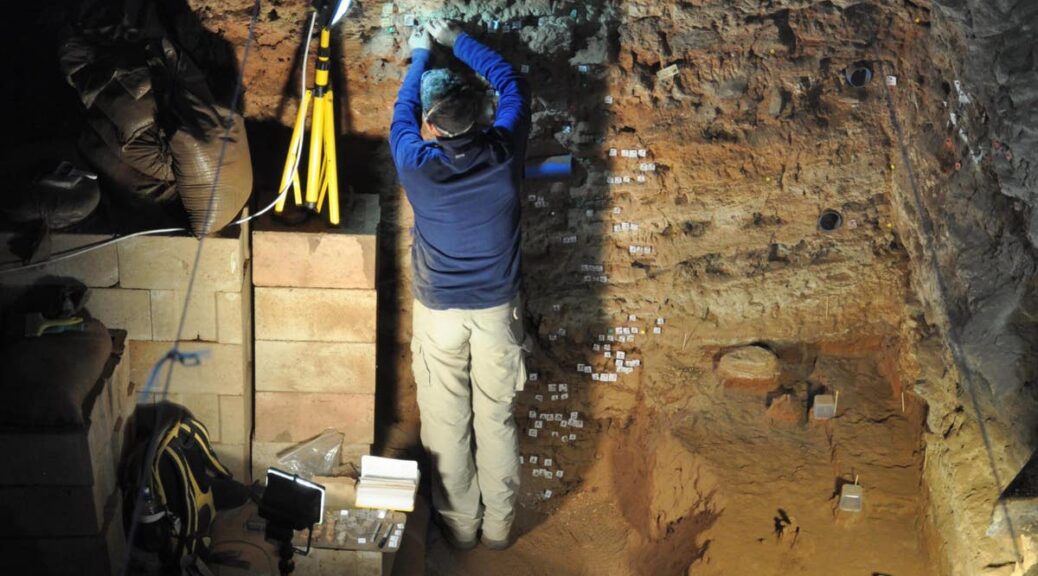

In 2009 two unopened scrolls from Herculaneum belonging to the Institut de France in Paris were placed in a Computerised Tomography (CT) scanner, normally used for medical imaging. The machine, which can distinguish different kinds of bodily tissue and produce a detailed image of a human’s internal organs could potentially be used to reveal the internal surfaces of the scroll. The task proved immensely difficult, because the scrolls were so tightly wound, and creased.

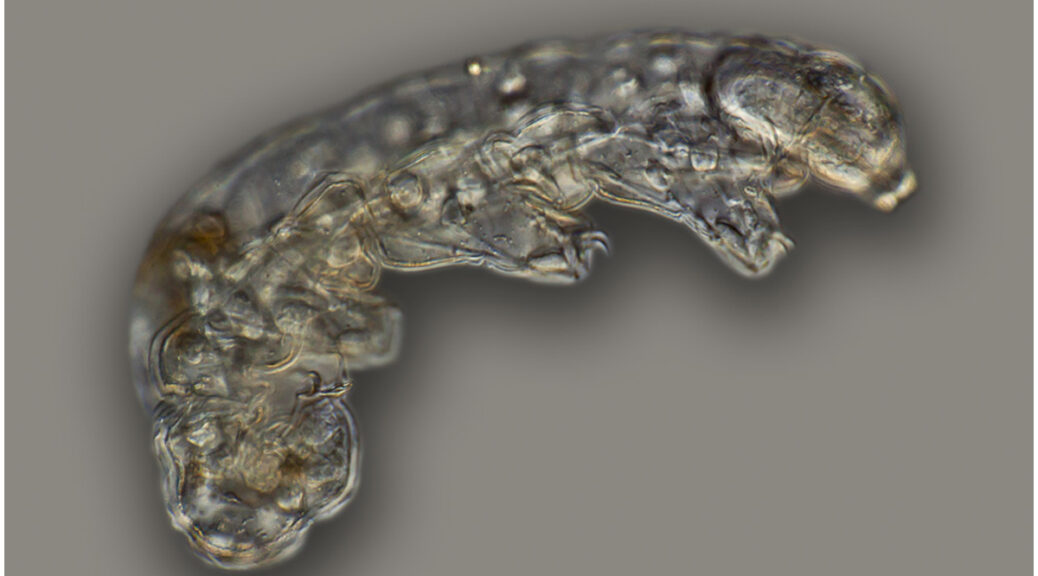

“We were able to unwrap a number of sections from the scroll and flatten them into 2D images – and on those sections, you can clearly see the structure of the papyrus: fibres, sand,” says Dr Brent Seales, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky, who led the effort.