South Africa’s Bandit Slaves And The Rock Art Of Resistance

Not all South African rock art is ancient; some dates back to the colonial period – and was created by runaway slaves. It tells a remarkable story.

With the founding of the Cape Colony in 1652, European colonists were forbidden from enslaving the indigenous Khoe, San and African farmers. They had to look elsewhere for a labour force. And so slaves, captured and sold as property, were unwilling migrants to the Cape, transported – at great expense – from European colonies like Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, the East Indies (now Indonesia), India and Sri Lanka.

Far cheaper was the illegal trade in indigenous slaves that grew in the borderlands of the colony. Khoe-San people were forced into servitude as colonists took both land and livestock. Together with immigrant slaves, they were the labour force for the colonial project.

Desertion was their most common form of rebellion. Runaway slaves escaped into the borderlands and mounted stiff resistance to the colonial advance from the 1700s until the mid-1800s. In most cases, the fugitives joined forces with groups of skelmbasters (mixed outlaws), who themselves were descended from San-, Khoe- and isiNtu-speaking Africans (hunter-gatherers, herders and farmers).

Thus, we find recorded examples of mixed bandit groups hiding out in mountain rock shelters, within striking distance of colonial farms. Using guerrilla-style warfare they raided livestock and guns. In their refuge, they made rock art, images within their own belief systems that relate to escape and retaliation.

These sites can be reliably dated because they include rock art images of horses and guns. In our most recent study of rock art in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, we see that this art also provides us with the raiders’ perspective. Our fieldwork enables us to view something of the slave and indigenous resistance from outside the texts of the colonial record.

The paintings

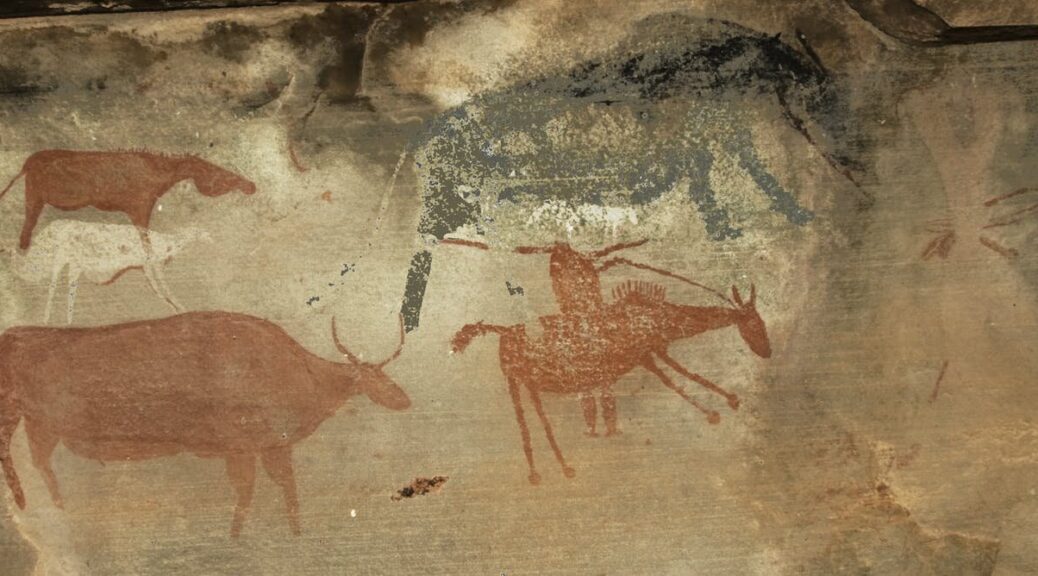

These mountainous regions house many rock shelters with paintings of the traditional corpus of ‘San rock art’ (antelope and dances) that have become world-famous. But owing to almost 2,000 years of contact with incoming African herders and farmers, the hunter-gatherer art changed in appearance, if not in the essence of its meaning. The ‘disconnect’ was most stark, however, during colonisation. The artists’ societies were deeply affected, disrupted and decimated. Where any art continued it was that of the mixed outlaws, often referred to simply as ‘Bushmen’ but who was actually a composite of many cultural backgrounds.

The paintings themselves are also mixed – some brush-painted, some finger-painted – but are united by subject matter pertaining to spiritual beliefs concerning escape and protective power. Certain motifs, including baboons and ostriches, continued to be used, but now appearing alongside motifs such as horses and guns. This suggests some continuity in the recognition of these animals, mystical or otherwise, as subject matter pertinent to people’s changed circumstances.

Despite these changes, bandit groups, however mixed they were, held onto, and even highlighted, some specific traditional beliefs.

Ritual specialists

The location of one band of mixed outlaws, in the Mankazana River Valley in today’s Eastern Cape, comes from the record of the 1820 settler, poet and abolitionist Thomas Pringle. During our fieldwork in this area we found rock paintings of horses, riders with guns and cattle raids that can be reliably dated to approximately when Pringle was writing.

That diverse groups of bandits painted depictions of cattle raids suggests that raiding was a fundamental concern for these groups. If we have learnt anything from the last five decades of southern African rock art research, it is that images are not the mere depictions of what the artists saw around them. Rather, they are of what ritual specialists see while travelling through the spirit world.

In the case of bandit groups, the ritual specialist often performed the role of war-doctor, who supplied traditional medicines to ensure protection in dangerous situations, including cattle raids and the flight from servitude.

It is telling that these images also include motifs relating to protection during raids as can be seen in the appearance of certain animals, especially baboons and ostriches.

Baboons are associated with protection across Khoe-San and African farmer society. The |Xam San people of the 1800s claimed that the baboon chewed a stick of so-/oa, a root medicine which would alert the user (animal or human) to approaching danger and keep it safe. Among the Xhosa there is a cognate belief in uMabophe – arguably the same root medicine. Like so-/oa, uMabophe was supplied by ritual specialists to those who wished to exert supernatural influence over projectile weapons, including turning ‘bullets to water’.

Protective animals

Many of these images are painted with a fine-line, unshaded technique. But there are also images that are finger-painted in black or bright orange pigment, which have a distinctly Khoe-speaker inflection. In technique they strongly resemble the art of the Korana raiders, to the north of the colony, who were known to take in runaway slaves.

Further into the hinterland, as if to mark the fighting retreat of bandit groups as the colonial frontier expanded, we discovered rock shelters in the Stormberg and Zuurberg that exhibit yet more features of an indigenous resistance idiom. In one are images of people with horses and guns, as well as baboons and ostriches.

The ostrich was recognised by Khoe-San groups as particularly adept at escaping danger. It could outrun most predators and leap over hunters’ nets. Khoe-San would, and still do, tie the tendons from ostrich legs to their own legs to combat fatigue. Ostrich eggshell was recognised as a medicine that could be ground and consumed as a fortifying tonic. In the art of bandits, images of ritual specialists transforming into ostriches or baboons attest to them drawing on the powers of protective animals to ensure their own escape from former captors or following stock raids.

The bandit’s view

Although never officially recognised as slaves, the Khoe-San were uprooted from their land and lifeways by European settlers and forced into bondage. This brought them into contact with immigrant slaves, alongside whom they often escaped. In defiance they raided their former captors and other settlers and in rocky hideouts they painted their concerns.

The rock art of bandit groups is bound up with beliefs in the ability to call upon the protection of the supernatural. Baboons and ostriches, painted with images of livestock and people on horseback with firearms, were heralded for their associated powers pertaining to escape and protection while raiding. For these runaway slaves, rock art was one of several crucial ritual observances performed to prevent the likelihood of ever returning to a life of oppression.