Jiroft Civilization, one of the oldest in the world

A major cultural center

For about a century we have been aware that ancient Persia was a major factor in the complex of populations that laid the foundations for the development of civilizations, but actual proof of this fact has been made available only through very recent discoveries. Now we know for certain that already in very ancient times this country played a leading role in the formulation and elaboration of technological and artistic progress.

The recent archaeological excavations carried out in southeast Iran demonstrate that, at the dawn of urban civilization, the Persian plateau and Susiana were just as important as Mesopotamia.

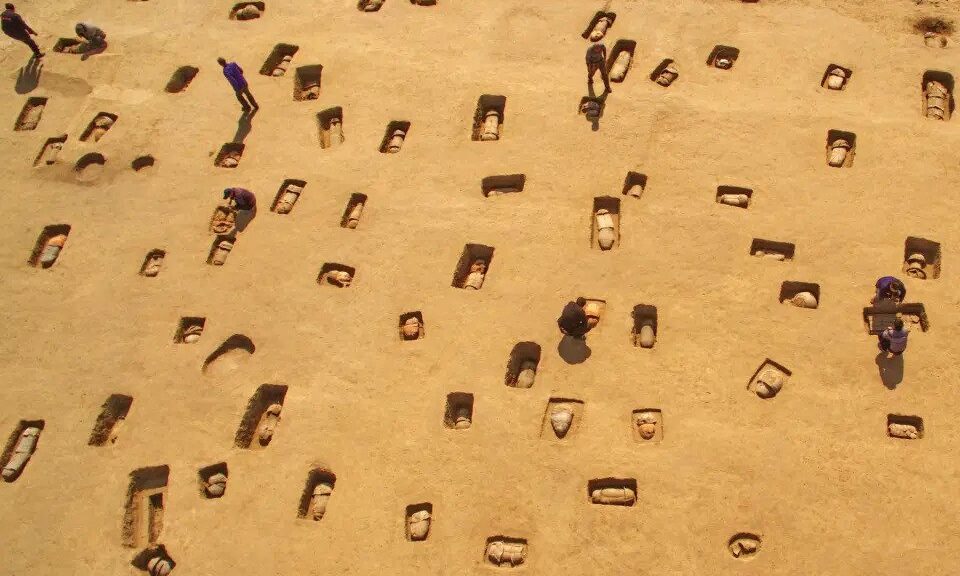

Archaeological research still in progress in the Halil Rud Valley, south of Kerman, was first concerned with protecting the prehistoric necropolises from clandestine, large-scale looting on the part of the inhabitants of the region.

Local people were systematically looting the tombs, and the stolen treasures were sent to the leading art markets in the Western world — London, Zürich, New York, etc. Taken out of their context, these objects lost their cultural importance and ended up having only commercial value, thereby becoming isolated and therefore ‘voiceless’ artifacts for historians, art historians, and anthropologists.

The official ban on plundering, together with the emergence of scientific surveys organized by Iranian archaeologists, have demonstrated that the region was the center of culture and art that developed around 3100 BC. The architectural and sculptural creations brought to light in the areas situated between Kerman and the Strait of Hormuz, at an altitude of 1968 ft (600 m) above sea level and in a region of palm orchards surrounded by mountains peaks over 13,000 ft (4000 m) high, are of the utmost importance and interest. The works unearthed by the archaeologists were contemporaneous with the flowering of Sumerian art at the ancient city of Ur, El Obeid, Uruk, or Telloh (Lagash), and in certain respects rival the production of these famous sites.

In Southeast Persia, there was a proto-Elamitic civilization that early on boasted a primitive form of writing, proof of which is provided by tablets brought to light at Tepe Sialk (Kashan, north of Isfahan), Tepe Yahya, and Susa.

The largest city in Elam in that period Was in fact Susa, situated at the confluence of the valleys of the Kherka and Karun rivers, which are perennial and flow into the Tigris and Euphrates in Lower Mesopotamia and then empty into the Persian Gulf. However, the digs carried out in these Khuzistan lowlands from 1883 on by the French mission at Susa ruined this site so badly that it is now impossible to establish chronological data with any degree of certainty. The aim of the excavations at that time was to concentrate on gathering objects (pottery and sculpture) rather than attempting to establish dates on the basis of the stratigraphy.

Consequently, archaeologists are now unable to provide precise dates for the superb pottery of Susa, which was unearthed over a century ago. The dates published by André Parrot in 1960 regarding these artifacts — the beginning of the IV millennium BC — must therefore be accepted with caution. In any case, we will return to this subject further on.

Present-day Excavations

The Iranian archeologist Youssef Majidzadeh who is now in charge of the research at the site of Halil Rud (in particular Jiroft, a locality after which the art of the region was named) has accumulated a collection of hundreds of delicately decorated stone objects. The special quality of the local material — a type of chlorite —makes it particularly suitable for sculpture: vases, bowls, cylindrical bottles, statuettes, weights (in the shape of ‘purses’), and animal figures, all accompanied by various ceramic objects.

Right Gazelles and predatory animals are represented on this Jiroft-style truncated cone vase in chlorite. Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva.

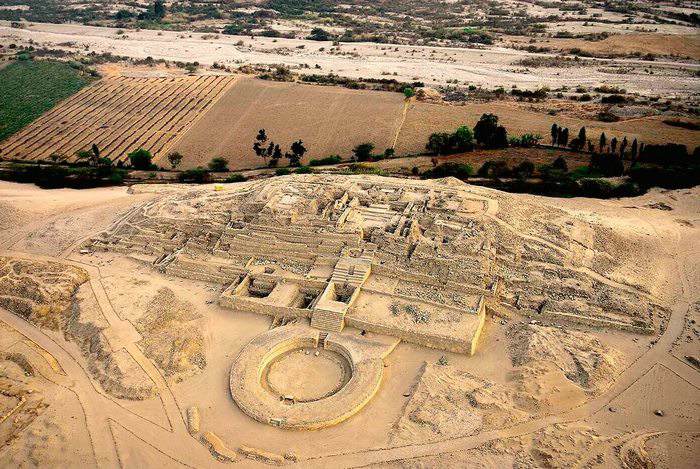

The research carried out at the tepes of Konar Sandal A and Konar Sandal B, carried out with stratigraphic excavations, has brought to light unfired brick ramparts that are 36 ft (11m) thick and has also unearthed terraces that crowned the uppermost part of the tepes.

These summit platforms, which arc from 36 to 50 ft (11 to 15 m) above the ground, have a surface area of about 10 acres (4 hectares), for centuries people lived here, repeatedly rebuilding their dwellings made of unfired bricks and clayey earth compressed with straw and rubble. Since this material was brittle, it could not resist the climate and the onslaughts of neighboring peoples or nomads, so the inhabitants had to continuously build new constructions over the ruined ones. This led to the creation of artificial mounds known as tepes.

Archaeologists identified 12, 15, or 18 superposed levels by digging carefully into these unique hillocks that dot the Iranian plateau, much like the tells in Mesopotamia.

One of the most amazing aspects of the culture that grew up in southeast Iran is the presence of a form of writing known as proto-Elamitic, which probably dates from the lVth millennium BC and was discovered on tablets whose inscriptions are now being studied meticulously in order to find a key to decipherment. The first tablets, discovered in Susa in 1901, consisted of about 200 pieces, and another 490 were found in 1923. In 1949 the specialists found 5,529 different signs.

Analogous tablets found at Tepe Sialk, near Kashan, have allowed scholars to consider the Iranian plateau the center of this early form of writing. Later on, the discovery of other tablets at Tepe Yahya, in the heart of the Jjroft site, proved that the cradle of this writing — like that of the chlorite sculpture — might very well be the Haul Rud region, south of Kerman.

Jiroft Ziggurat – Origin of the Concept

An entire repertory is given over the motif of architecture, which is another amazing subject in the artistic production of this time. On cylindrical bowls, there are images of regular facades, with pilasters that form tall plinths.

The chambers with doors and windows are surmounted by flexed architraves, whose curves seem to be produced by the weight of the structure on rather feeble palm-tree trunks. However, the most striking motifs are the images of constructions in the shape of ziggurats. Many cylindrical vases have representations of an edifice with three or four gradually receding stories, which reflect the concept of the classical Mesopotamian ziggurat. This type of object is often surmounted by a pole or ‘horn,’ which according to later Babylonian texts indicates their sacred nature. Now while the decorated vases at Jiroft have been dated at 3100-2600 BC, these small ziggurats from the Persian steppes seem to be more ancient than the structures built in the Mesopotamian plain, which are similar in some respects but much more impressive.

This fact alone means that Persia was the wellspring of these ‘artificial mountains,’ the enormous stepped bases of the temples that dotted the Land of Two Rivers (the Tigris and Euphrates). It is even possible that the storied tower originally crowned the tall terrace of the tepes, thus becoming the top part of a city as well as its religious symbol and insignia of power

At this stage, mention should be made of the votive or emblematic pieces representing tall perforated images of animals (eagles, scorpions, and even men-scorpions). These objects, which were carved tablets, have engraved guilloche decoration (interlaced bands with openings containing round devices) that is animated by polychrome stones. In this case, only a function connected to power — a ‘royal’ insignia or sacred symbol of a priest — would explain the motive behind such creations, which are from 12 to 15 inches (30 to 40 cm) high and may have been used as scepters.