A medieval cargo ship unexpectedly found during construction work in Estonia

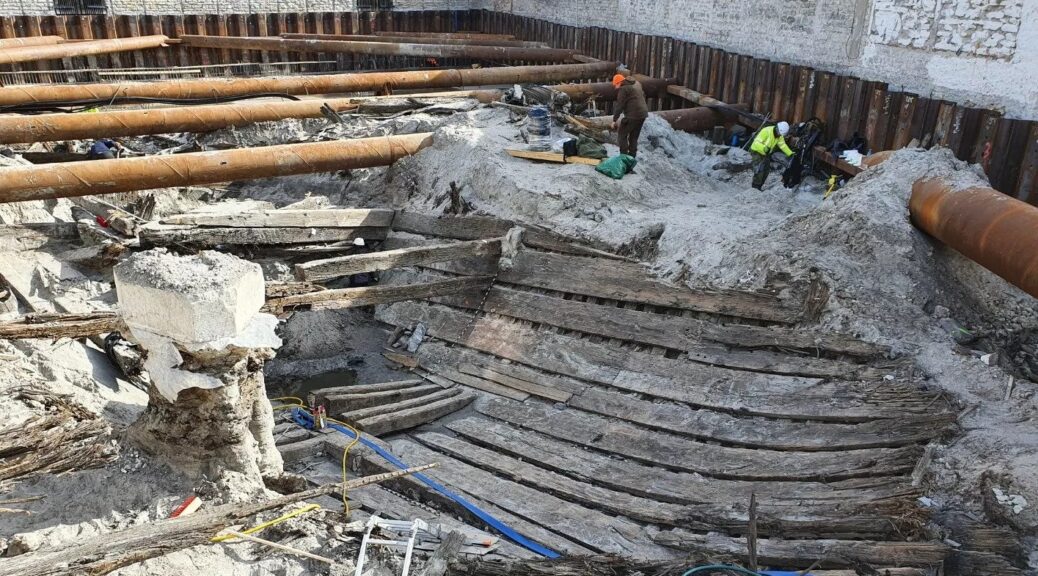

Construction workers have found the battered remains of a 700-year-old ship under the streets of the Estonian capital of Tallinn. Buried approximately 5 feet (1.5 meters) underground, the remnants of the ship are made of oak and are just over 78 feet (24 m) long with a beam, the ship’s widest point, measuring about 29 feet (9 m) across.

“The original length of the ship was bigger since the stempost [the vertical timber at the bow] is missing and the bow of the ship is damaged,” Priit Lätti, a researcher at the Estonian Maritime Museum, told Live Science in an email.

“The ship was probably built at the beginning of the 14th century,” according to dendrochronological analysis, an examination of the tree rings found in the ship’s wooden remains, he said. The ship is, at first glance, very similar to other ships found in Europe from the same time period, he added.

Unearthed near Tallinn’s Old Harbor three weeks ago, the ship was a significant find for archaeologist Mihkel Tammet, who had been observing a construction project.

According to Lätti, when areas under heritage protection are being excavated, an archaeologist must be present. The Estonian Maritime Museum was notified of the ship’s discovery to help provide more information and record the find.

The ship was not buried very deep, and as Lätti told Live Science, it was filled with sand. It’s likely the sea gradually filled the boat over the centuries, as different layers of sand were visible, he said.

Since the discovery of the ship, there has been speculation that it is a Hanseatic cog(opens in new tab), a cargo ship used for trade by the Hanseatic League.

The league, a group of trade guilds from across Europe, dominated the seas between the 13th and 15th centuries. However, Lätti said it is too early in the excavation process to be able to accurately determine the origins of the ship.

“Very probably, it is a cargo ship,” he said. “Since we do not yet know the origin of the timbers (the dendrochronological analyses are still preliminary, so I do not want to mention exact dates or first ideas about the origin of the timber) it is hard to tell the origin of the vessel.”

Researchers are also working to determine whether further artefacts found buried with the ship can be of use when determining the age of the boat. “Additional analyses have been taken; also the artefacts found aboard must be analysed to give more exact answers, Lätti added.

“At the moment, only the bow area of the ship is excavated; the cargo hold was relatively empty. Now the excavations move to the aft area of the ship, which may contain more finds.”

Other artefacts uncovered with the ship so far include a couple of wooden barrels, pottery, animal bones, some leather objects and textiles. The number of finds is expected to increase in the coming days as the aft part of the ship is excavated.

The discovery of the ship in such a well-preserved condition is significant, as it will help historians and archaeologists learn more about shipbuilding and trade in the Middle Ages, as well as what life was like onboard these ships.

“For Tallinn as an old merchant town, finding something like this is an archaeological jackpot,” said Lätti, who specializes in studying harbours and shipwrecks. “The development of Tallinn is closely related to maritime trade, and while we know quite a lot about the merchants and merchandise, we still know relatively little about the ships they used.”

Ships similar to this one have been discovered in the past. For example, the Bremen cog(opens in new tab) was found in Germany in 1962, and a medieval cargo ship was uncovered in Tallinn in 2015 and is now housed in the Estonian Maritime Museum.

The future of this ship, after it has been excavated, is still under discussion. But the aim is to remove it from the construction site where it was found and house it in a controlled environment and preserve it. Lätti described this as a “huge task.”

“The methods of transporting, preserving and conserving the ship are still discussed,” he said, “because it is a very complex operation, and we are dealing with a very valuable archaeological object.”