Millet bread and pulse dough from early Iron Age South India: Charred food lumps as culinary indicators

Prof. Jennifer Bates and her coworkers, Kelly Wilcox Black and Prof. Kathleen Morrison, published a new archaeobotanical article, “Millet Bread and Pulse Dough from Early Iron Age South India: Charred Food Lumps as Culinary Indicators, ” in the Journal of Archaeological Science (Vol.137).

Jennifer is a former Postdoc in the Penn Paleoecology Lab, now an Assistant Professor at Seoul National University, Kelly is a PhD student at the University of Chicago, completing her dissertation. Kathleen is a Professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

In the paper, the authors explore charred lumps from the site of Kadebakele, in southern India, where they have excavated for several years with the support of the Archaeological Survey of India and colleagues.

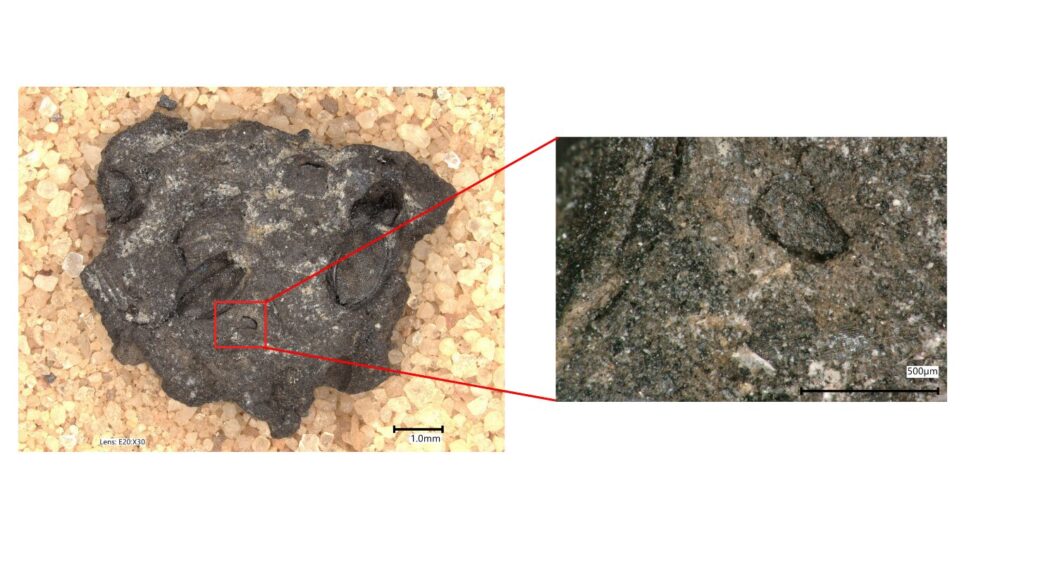

The site dates from around 2,300 BCE to CE 1600 or so, but these data are from the Early Iron Age, about 800 BC. Charred lumps are usually seen as not identifiable, but using high-quality imaging, they were able to show that (some of) these are charred remains of dough or batter; these would have been used to make bread-like dishes.

Comparing the data with experimental studies done by another lab group, they identified two kinds of food lumps, along with cattle dung lumps (likely fuel).

They found a dough made primarily from millets that match the experimental results of “flatbreads” most closely. Millet flatbreads are still made in this region.

There was also a batter made primarily from pulses (beans, lentils, etc.). This highlights the great importance of pulses in the diet, something is also seen in the overall botanical assemblage.

As far as we know, there hasn’t been any previous understanding of how these foods might have been prepared, and this paper is the first glimpse at food making in South Asian prehistory.

The work contributes to our understanding of cooking, diet, and daily life in the South Indian Iron Age, a period without historical documents, and also establishes the value of a data source previously assumed to be too difficult to study on a routine basis (that is, without using SEM).

Professor Bates, Ms Wilcox Black and Professor Morrison argue that work like this allows archaeologists to move beyond “taxa lists” (lists of plants and animals used — you could think of these as possible ‘ingredients’) to approach issues of culinary practice (combinations of ingredients as well as techniques).