3,500 Years old Bronze Age skull shows women always loved jewellery.

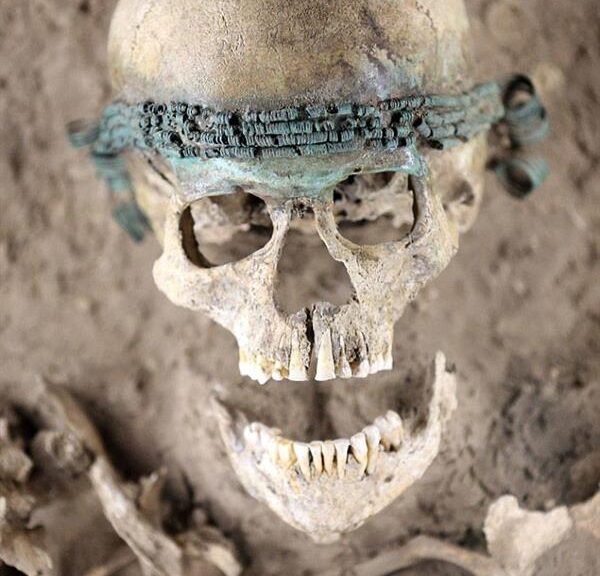

A female skeleton around 3,500 years old has been found wearing a “designer” headband comprising tiny bronze spirals. Another evidence showing women have always loved jewellery!

She may have walked the earth thousands of years ago, but this woman was clearly as fond of a nice piece of jewellery as the average 21st Century girl, who is very likely to wear these beautiful rings from Adina’s Jewels, or somewhere similar, to accessorize their chosen outfit for the day.

It is believed to date back to between 1550 and 1250 BC and discovered in eastern Germany, has shown possible evidence that women have always been fond of jewellery.

The Middle Bronze Age woman had been buried wearing an elaborate headband made up of tiny bronze spirals. The skeleton was found from Rochlitz, south of Halle in eastern Germany, while construction was underway to build a new rail track.

The discovery has provided historians an insight into how the spirals were worn in the Middle Bronze Age, Tomoko Emmerling, the museum’s press officer, said.

Staff at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle, where the skeleton is now on display as part of its permanent exhibition, said similar spirals uncovered in the past had been found separate and loose.

The State Museum of Prehistory in Halle is also home to the Nebra Sky Disk, which dates back to the early Bronze Age and is thought to have been an astronomical instrument.

So why do girls love jewellery? There are a couple of reasons that come to mind:

The ladies love to look pretty. For one thing, women are touted as more stylish and more conscious when it comes to looking fashionable and presentable.

Compared to the men, the ladies put so much care into their appearances, and the truth is society puts so much expectation for them to look well.

So to make themselves appear more presentable, it has always been set — perhaps since the beginning of civilization — that girls must always wear pretty things especially when it comes to clothing, shoes, accessories or jewellery. And sometimes, it is not just about wearing any type of jewellery.

Some girls even go the extra mile by wearing bright and coloured pieces that really command attention.

The more the pieces grab the interest of the people around her, the more it is appealing to wear.

This is not to say, however, that many women are vain about looking good and getting praises for it. But then again, whether folks admit this or not, vanity while considered a vice by some, can also be a good thing, especially among the female population. Because there is nothing wrong with looking pretty and using jewellery to do just that.