Scientists Finally Discover Ancient Blueprints Showing How The Pyramids Were Built.

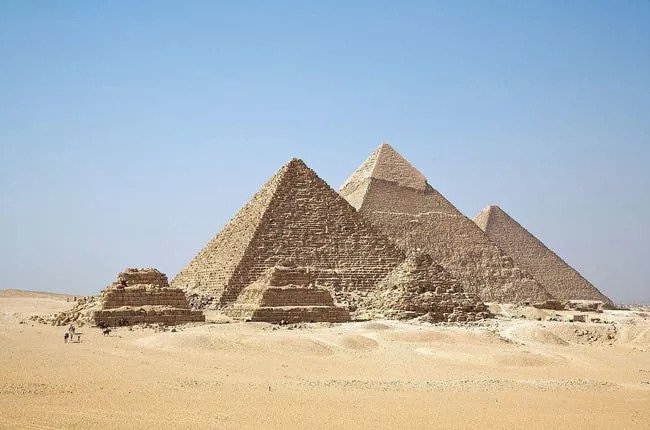

Built 4,500 years ago during Egypt’s Old Kingdom, the pyramids of Giza are more than elaborate tombs — they’re also one of the historians’ best sources of insight into how the ancient Egyptians lived since their walls are covered with illustrations of agricultural practices, city life, and religious ceremonies. But on one subject, they remain curiously silent. They offer no insight into how the pyramids were built.

It’s a mystery that has plagued historians for thousands of years, leading the wildest speculators into the murky territory of alien intervention and perplexing the rest. But the work of several archaeologists in the last few years has dramatically changed the landscape of Egyptian studies. After millennia of debate, the mystery might finally be over.

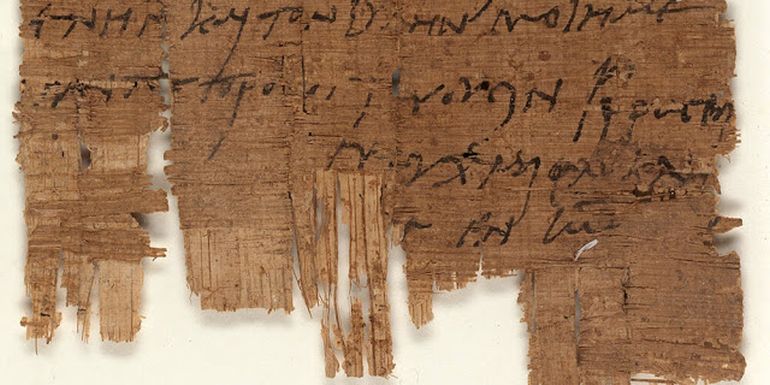

Researchers Discovered The Only First-Person Account Of The Great Pyramid’s Construction

A team of Egyptian and French scholars discovered a papyrus diary written by an official named Merer. What makes this discovery so compelling is that his diary is the world’s sole first-person description of how the Great Pyramid was built. Archaeologists found Merer’s papyrus in the Red Sea port of Wadi al-Jarf.

In his diary, Merer references working for “the noble Ankh-haf,” who was Pharaoh Khufu’s half-brother, and that he was in charge of about 40 men. These documents evidence that Ankh-haf was one of those in charge of the Great Pyramid’s construction.

The Pyramid’s Limestone Was Transported Via A System Of Canals

In Merer’s diary, he recounts how limestone quarried in Tura (about 12 miles south of Cairo) was transported by boat across the Nile River to Giza through specially built canals built by his team. One such vessel was unearthed at the bottom of the pyramids.

After traversing the river, the stone blocks were then deposited near the building site by workers using ropes. The blocks were further moved on tracks. The workers transported approximately 170,000 tons of limestone in this manner.

It’s believed a similar system was used to move granite from Aswan, which is located several hundred miles from Giza.

The Pyramid’s Stone Blocks Are Massively Heavy

Around 2550 B.C., Pharaoh Khufu started construction on the Great Pyramid at Giza. It is made up of approximately 2.3 million stone blocks. Each block is absolutely massive and weighs between 2.5 to 15 tons. When the Great Pyramid was built, it was reportedly 481 feet tall. Over time, the structure sunk a little into the desert and is now 455 feet tall.

The second pyramid was built about 30 years later by Khufu’s son, Pharaoh Khafre, who also constructed the Sphinx. Pharaoh Menkaure built the third, smallest, pyramid 30 years later, in approximately 2490 B.C.

Egyptians Traveled Far To Mine Copper For The Tools To Cut The Stones For The Pyramids

The individuals who built the pyramids required strong tools to cut the stone for the pyramids. Workers mined copper across the Red Sea and transported it to the port of Wadi al-Jarf before it reached Giza. Pharaoh Khufu, also known as King Cheops, built the harbor about 111 miles from Suez – which is hundreds of miles from Giza. In addition to copper, the harbor was used to import other minerals for tool making.

Some Historians Believe The Pyramid Required 100,000 Workers

It’s impossible to agree upon an exact count of just how many people contributed to the building of the pyramids, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t educated hypotheses currently being postulated. According to Greek historian Herodotus, the pyramids were built by 100,000 workers, although many of today’s Egyptologists think the number is more likely between 20,000 and 30,000.

Famed Egyptologist, Zahi Hawass, believes around 36,000 ancient Egyptians built the pyramids based on their size, the size of the tombs, and the cemetery.

Other Historians Think Only 5,000 Workers Contributed To The Pyramid Building Process

Archeologist Mark Lehner of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and Harvard Semitic Museum has postulated a vastly smaller number. He noted that Herodotus wrote that 100,000 men worked in three shifts to build the structures. It’s unclear whether each shift contained 100,000 men or 33,000 men worked in each of the three shifts.

Lehner’s team conducted an experiment and calculated how many men would be needed to deliver 340 stones each day and determined there were likely 1,200 in the quarry and 2,000 delivering the stones. Other men would also be needed to cut the stones and set them into place. He concluded the process would have required “5,000 men to actually do the building and the quarrying and the schlepping from the local quarry” to build the pyramid within a 20-40 year period.

The Pyramids’ Alignment Points To An Alien Conspiracy

Some people believe the ancient Egyptians had some otherworld help creating the pyramids. One theory that conspiracy theorists have latched on to is that the pyramids were built by aliens. Their proof? They point out that the pyramids at Giza align with the stars in the sky that form Orion’s belt. In addition, these people believe that the Giza pyramids are in extraordinary shape compared to pyramids that were constructed hundreds of years later.

However, they don’t take into consideration the fact that the pyramids of Giza have undergone intense preservation over the years so it makes sense that they are in better condition than those that haven’t been touched.

Dutch Physicists Believed The Ancient Egyptians Used Wet Sand To Drag The Blocks Across The Desert

In 2014, researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter conducted an experiment. They transported heavy stone on a sledge across the sand. They proved it was significantly easier to move the sledge on damp sand versus dry sand. In fact, the action required just half the force. The reason? Wet sand sticks to itself and is more solid than dry sand. Plus, damp sand doesn’t bunch up in front of a sledge while it’s moving. In addition, the researchers noted that a painting from an 1800 B.C. tomb depicted a worker dumping water on the sand to help a sledge moving a heavy statue.

Another Theory: The Stones Were Turned Into 12-Sided Polygons & Rolled To The Site

Dr. Joseph West of Indiana State University developed his own theory about how the stone blocks were moved to the pyramid’s construction site. In 2014, he suggested that builders might have secured wooden beams to a stone block, turning it into a dodecagon (a 12-sided object), which would have enabled workers to more easily move them, as opposed to dragging them. He wrote:

A novel method is proposed for moving large (pyramid construction size) stone blocks. The method is inspired by a well known introductory physics homework problem and is implemented by tying 12 identical rods of appropriately chosen radius to the faces of the block. The rods form the corners and new faces that transform the square prism into a dodecagon which can then be moved more easily by rolling than by dragging.

The Pyramid Were Actually Constructed From Concrete

French theorist Joseph Davidovits was on the right path. His ideas led to the discovery of concrete blocks that were used on top of the pyramids. Professor Michel Barsoum from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Drexel University tested Davidovits’s theory and determined several things. The stones both inside and outside the pyramid appeared to be “reconstituted” limestone.

The stones contained a lot of water and were amorphous, which is extremely unusual for limestone. Moreover, silicon dioxide nanoscale spheres were present in one sample, indicating the blocks were not “natural” limestone.

Barsoum noted:

It’s very improbable that the outer and inner casing stones that we examined were chiseled from a natural limestone block.

Perhaps The Pyramids Were Built Inside Out

When it comes to placing the large stone blocks in place on the pyramids, many believe the ancient Egyptians used large ramps. Thousands of people would have been required to set two million blocks to make the structures.

In 2013, engineer Peter James, whose company spent nearly two decades restoring the pyramids, disputed that claim. He called it “impossible” because the ramps would have had to be about one-quarter mile long. Otherwise, they would be too steep to move the limestone and granite materials. Instead, James theorized that the workers crafted the inner core of the pyramid with smaller blocks using a series of zigzagging ramps.

Then they constructed scaffolding to complete the outer core with larger blocks. James told the Daily Mail:

Looking at the pyramids from a builder’s point of view, and not an archaeologist’s, it’s clear that the current theories are nonsense. Just look at the numbers. Under the current theories, to lay 2 million blocks, the Egyptians would have to have laid a large block once every three minutes.

It would have been impossible to build the pyramids using ramps around the outside, too, because they would have ended up being larger, in some cases, than the pyramids themselves. Plus, what happened to the ramps once the pyramids were finished? I believe the Egyptians built the pyramids like a modern-day builder builds a house.