Children’s Teeth Reveal Breastfeeding Practices in Ancient Peru

For thousands of years, breastfeeding habits have remained almost unchanged in the Peruvian Andes, according to an unprecedented research project at an archaeological site in Caral, the oldest civilisation in the Americas and the origin of Andean culture.

There, in a cemetery filled with the bodies of children believed to be buried around 500 B.C., researchers discovered that the way these kids were breastfed was akin to how mothers do it in modern-day rural communities in the Andes.

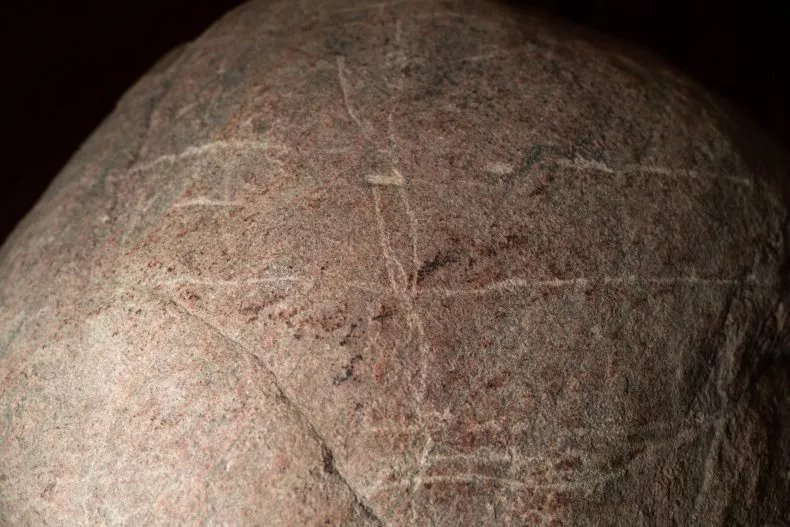

Tooth analysis of the remains of 48 children showed that the majority were breastfed exclusively for the first six months and were not completely weaned until 2.6 years of age, which is still the case in the most rural and traditional Andean populations.

“We expected a younger age, like in modern times, where due to work issues and social pressures, children are weaned practically at 9 months,” Luis Pezo-Lanfranco, the Peruvian bioarchaeologist leading the study, tells Efe.

Pezo-Lanfranco says that it is very likely intermittent breastfeeding occurred in Caral, the civilization that developed 130 kilometres (over 80 miles) north of Lima between the years 3,000 to 1,800 B.C.

To be sure, researchers need to find a cemetery from that period. A few burial sites from that time in Caral have been recovered but the preservation of bones was too poor to find stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, which reveal breastfeeding patterns.

Researchers are nevertheless confident that those breastfeeding habits found in infants buried in Chupacigarro ravine cemetery, just a kilometre from the sacred city of Caral, were inherited from the Americas’ first civilization.

“In Caral, many cultural forms were created that are traditional for the Andes,” says Pedro Novoa, deputy director of Caral research and conservation of materials.

While the discovery of a cemetery that would confirm the Caral researchers’ hypothesis has evaded them, indications of the significance that breastfeeding held in this primitive society have been found in several nearby urban centres.

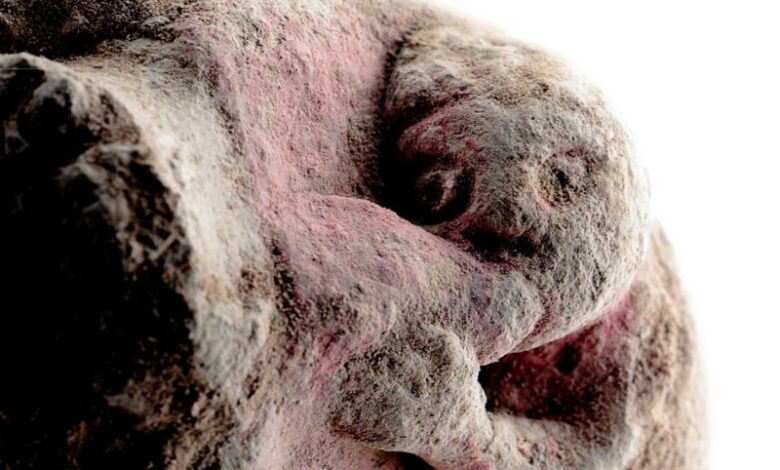

It can be seen in a series of clay statuettes representing women breastfeeding their infants and others who hold their babies in their laps, in an allegory of motherhood discovered in Vichama, one of Caral’s 12 urban centres.

According to the study, it is still not clear whether that long breastfeeding period was a nutritional supplement or was due to food shortages.

Ruth Shady, the director of Caral archaeological investigations, says the high infant mortality may have been due to drought and famine.

“The drought is the main problem they faced, and it is very possible that this was what caused death among these children,” adds Shady, who has been studying Caral since 1994.