Ancient ostrich eggshell reveals new evidence of extreme climate change thousands of years ago

Evidence from an ancient eggshell has revealed important new information about the extreme climate change faced by human early ancestors.

The research shows parts of the interior of South Africa that today are dry and sparsely populated, were once wetland and grassland 250,000 to 350,000 years ago, at a key time in human evolution.

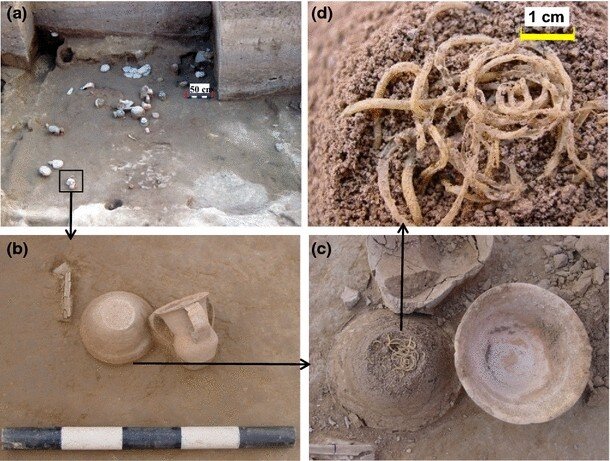

Philip Kiberd and Dr Alex Pryor, from the University of Exeter, studied isotopes and the amino acid from ostrich eggshell fragments excavated at the early Middle Stone Age site of Bundu Farm, in the upper Karoo region of the Northern Cape.

It is one of very few archaeological sites dated to 250,000 to 350,000 in southern Africa, a time period associated with the earliest appearance of communities with the genetic signatures of Homo sapiens.

This new research supports other evidence, from fossil animal bones, that past communities in the region lived among grazing herds of wildebeest, zebra, small antelope, hippos, baboons and extinct species of Megalotragus priscus and Equus capensis, and hunted these alongside other carnivores, hyena and lions.

After this period of equitable climate and environment the eggshell evidence — and previous finds from the site — suggests after 200,000 years ago cooler and wetter climates gave way to increasing aridity. A process of changing wet and dry climates recognised as driving the turnover and evolution of species, including Homo sapiens.

The study, published in the South African Archaeological Bulletin, shows that extracting isotopic data from ostrich eggshells, which are commonly found on archaeological sites in southern Africa, is a viable option for open-air sites greater than 200,000 years old.

The technique which involves grinding a small part of the eggshell, to a powder allows experts to analyse and date the shell, which in turn gives a fix on the climate and environment in the past.

Using eggshells to investigate past climates is possible as ostriches eat the freshest leaves of shrubs and grasses available in their environment, meaning eggshell composition reflects their diet.

As eggs are laid in the breeding season across a short window, the information found in ostrich eggshells provides a picture of the prevailing environment and climate for a precise period in time.

Bundu Farm, where the eggshell was recovered is a remote farm 50km from the nearest small town, sitting within a dry semi-desert environment, which supports a small flock of sheep.

The site was first excavated in the late 1990s the site with material stored at the McGregor Museum, Kimberley (MMK). The study helps fill a gap in our knowledge for this part of South Africa and firmly puts the Bundu Farm site on the map.

Philip Kiberd, who led the study, said: “This part of South Africa is now extremely arid, but thousands of years ago it would have been Eden-like landscape with lakes and rivers and abundant species of flora and fauna.

Our analysis of the ostrich eggshell helps us to better understand the environments in which our ancestors were evolving and provides an important context in which to interpret the behaviours and adaptations of people in the past and how this ultimately led to the evolution of our species.