Fifth-Century A.D. Cemetery Uncovered in the Czech Republic

Expats CZ reports that six graves dated to the fifth century A.D. have been found in the East Bohemia region of the Czech Republic. One of the graves was intact, according to archaeologist Pavel Horník of the Museum of Eastern Bohemia, while the others had been looted shortly after the burials took place.

The site was discovered in 2019 by archaeologists from the Museum of Eastern Bohemia in Hradec Králové (MVČ HK), and the first findings were just made public. The site has been dated to the fifth century AD, around the time of the collapse of the western part of the Roman Empire and the start of the Dark Ages. The era was known for migration and instability.

Graves from this time are rare. “In Eastern Bohemia, this is only the second chamber grave from the period of the migration that has been explored.

The first in the region was a grave in Plotiště nad Labem, discovered in the 1960s. It was the burial of an elderly man with a child,” MVČ HK archaeologist Pavel Horník said.

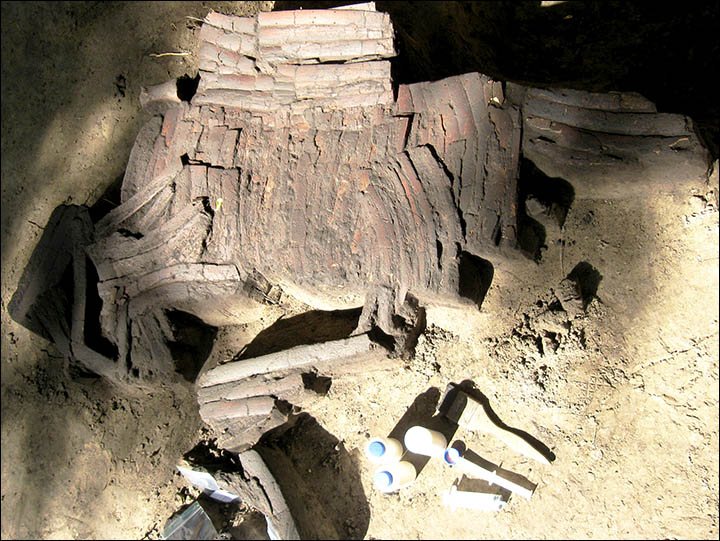

One of six graves in the newly discovered site at the village of Sendražice, just outside the city of Hradec Králové, was exceptional. It had escaped the attention of grave robbers who plundered the other five shortly after the burials took place.

“Most of the graves were looted in the spirit of those times. An exception was the grave belonging to a woman between 35 and 50 years old. This grave can be described as extraordinary in the whole of the Czech Republic,” Horník said.

The artefacts from all of the graves are being examined by experts from Masaryk University in Brno, the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague, the Institute of Archeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, the Mining Museum in Příbram, and the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

Precious and mundane items both yield secrets

The intact grave chamber, designated grave number two, contained several items of extraordinary historical and artistic quality such as four silver-and-gold clasps inlaid with semi-precious stones and a headdress decorated with gold targets.

Remnants of two different textiles were on the silver-and-gold clasps in the unlooted grave. One of the fabrics belonged to the garment fastened by the buckles, the other to a coat of cloth that covered the woman.

Remains of leather and fur were also found on the buckles, according to research by Helena Březinová from the Institute of Archeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

The other five graves were for people between the ages of 16 and 55. While they had been looted, they still contained the remains of funeral offerings such as a short sword, knives, glass and amber beads, metal belt components, decorative shoe fittings, and antler combs.

From the looted grave number five, only an iron knife, beads, and a ceramic vessel survived. Samples from the vessel showed that meat had been cooked in it. The presence of certain acids and fats indicates it was the meat of a ruminant, such as a cow. There were no indications of the presence of plant-based food in any of the graves.

Diseases reveal a hard life

Arthritis was evident in the bones of one of the buried people, possibly due to age and physical exertion. Anthropologist Milada Hylmarová of Masaryk University noted significantly asymmetrical muscles on the lower limbs in one of the graves. Due to the incompleteness of the skeleton, the cause can’t be determined but it could be the result of a stroke.

In another case, traces of cancer were found on a skull and pelvis. Other ailments noted were tooth decay and damage to joints.

High-tech examinations underway

Research is continuing, and should eventually reveal a more complete picture of the lives of the people from the site. The chemical composition of the ceramic vessel could reveal whether it was manufactured in the area or came from elsewhere.

So far, only the gender of the woman in the unlooted grave has been determined with any certainty. Based on the objects found, it is assumed that a man was buried in grave number three and a woman in grave six.

DNA analysis is currently taking place in cooperation with the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig and the Institute of Archeology and Museology of Masaryk University. This could show more about the relationships between the people and where they came from.