Archaeologist Discover Paintings of Goddess in 3,000-year-old mummy’s coffin

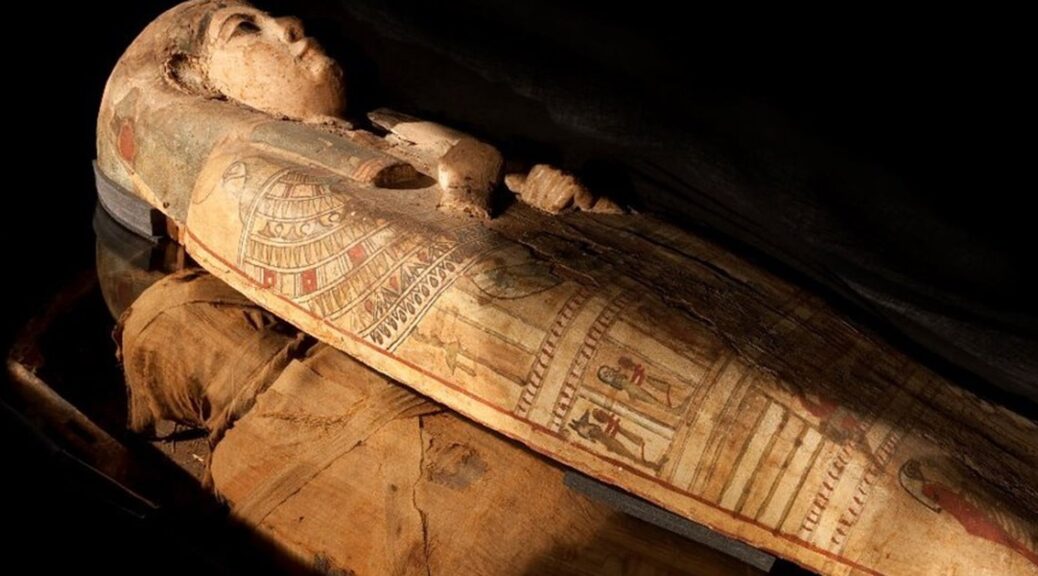

In the coffin of an Egyptian mummy, paintings were found after she was taken out for the first time in over a hundred years.

In the campaign to preserve Ta-Kr-Hb – pronounced “takerheb” – a priestess or princess from Thèbes, a Scottish conservative made this discovery.

Despite having been robbed by serious robbers throughout history, the mummy, almost 3000 years old, was in a fragile state.

The research was done before her remains are exhibited at Perth’s new City Hall Museum, Scotland to ensure that her condition didn’t further deteriorate. The conservatives were shocked that when Ta-Kr-Hb was removed, painted figures from the Egyptian goddess were found on the inner and outer bases of the trough.

Both figures are representations of the Egyptian goddess Amentet or Imentet, known as the ‘She of the West’ or sometimes ‘Lady of the West’.

‘It was a great surprise to see these paintings appear,’ Dr. Mark Hall, collections officer at Perth Museum and Art Gallery, told the PA news agency.

‘We had never had a reason to lift the whole thing so high that we could see the underneath of the trough and had never lifted the mummy out before and didn’t expect to see anything there.

‘So to get painting on both surfaces is a real bonus and gives us something extra special to share with visitors.’

Further research will be carried out on the paintings to find out more about the history of the mummy, believed to date from somewhere between 760 and 525 BC. The painting on the interior base of the coffin trough was previously hidden by Ta-Kr-Hb and is the best preserved of the two.

It shows Amentet in profile, looking right and wearing her typical red dress. Her arms are slightly outstretched and she is standing on a platform, indicating the depiction is of a holy statue or processional figure.

Usually, the platform is supported by a pole or column and one of these can be seen on the underside of the coffin trough. The mummy was donated to Perth Museum by the Alloa Society of Natural Science and Archaeology in 1936.

It was presented to the society by Mr. William Bailey, who bought it from the curator of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In 2013, Ta-Kr-Hb was transferred temporarily for a ‘check-up’ at Manchester Royal Children’s Hospital, which included a CT scan and X-rays of her coffin.

Radiographic examinations revealed that her skeleton had suffered extensive damage to the chest and pelvis, sometime after the body had been mummified, according to SCBP Perth.

While the skull remains intact, radiography revealed that as part of the mummification process the brain mass was removed through the sinuses.

But the full removal of Ta-Kr-Hb’s remains this year allow today’s researchers to closely observe the paintings beneath. Perth Museum and Art Gallery are now hoping to save ‘Ta-Kr-Hb’ – as written in hieroglyphics on the lid of her coffin – for future generations.

‘The key thing we wanted to achieve was to stabilize the body so it didn’t deteriorate any more so it has been rewrapped and then we wanted to stabilize the trough and upper part of the coffin which we’ve done,’ said Dr. Hall.

‘Doing this means everybody gets to find out a lot more about her.

‘One of the key things is just physically doing the work so we have a better idea of the episodes Ta-Kr-Hb went through in terms of grave robbers and later collectors in the Victorian times so we can explore these matters more fully and we can share that with the public.’

Conservators Helena Jaeschke and Richard Jaeschke have been working closely with Culture Perth and Kinross on the project, which started work in late January. Culture Perth and Kinross are campaigning to raise money for the conservation of Ta-Kr-Hb as she prepares to go on display at the Perth City Hall Museum, which is set to open in 2022.