The Mysterious Bronze Objects That Have Baffled Archaeologists for Centuries

One August day in 1987, Brian Campbell was refilling the hole left by a tree stump in his yard in Romford, East London, when his shovel struck something metal.

He leaned down and pulled the object from the soil, wondering at its strange shape. The object was small—smaller than a tennis ball—and caked with heavy clay. “My first impressions,” Campbell tells Mental Floss, “were it was beautifully and skillfully made … probably by a blacksmith as a measuring tool of sorts.”

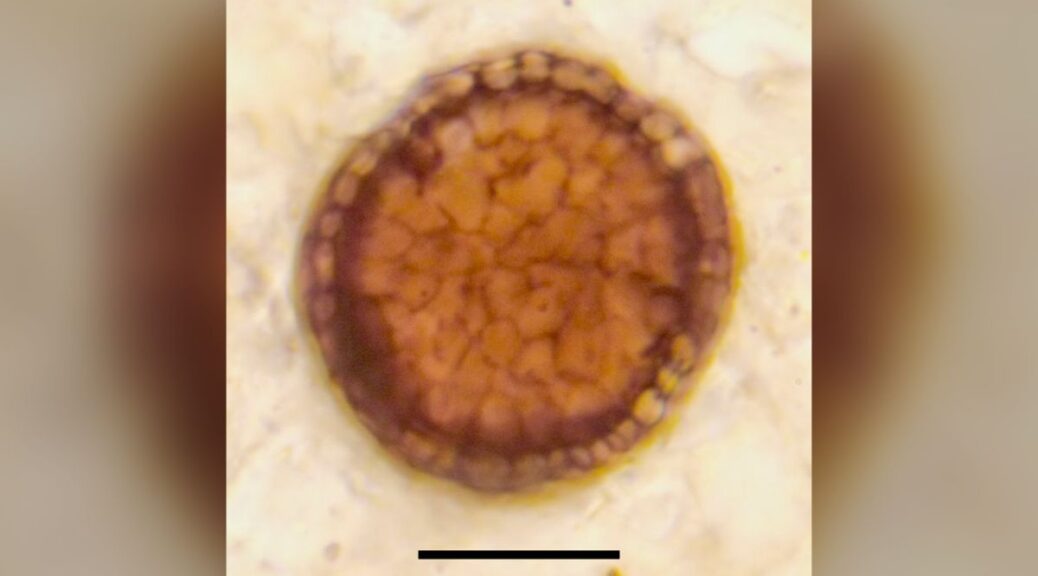

Roman dodecahedra date from the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD and typically range from 4cm to 11cm (1.57-4.33 inches) in size. To date, more than one hundred of these artefacts have been found across Great Britain, Belgium, Germany, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, and Hungary.

What were Roman Dodecahedra Used for?

The great mystery is: how do they work and what do they do? Unfortunately, there is no documentation or notes about them from the time of their creation, so the function of the dodecahedra has not been determined.

Nevertheless, many theories and speculations have been put forward over the centuries: candlestick holders (wax was found inside one example), dice, survey instruments, devices for determining the optimal sowing date for the winter grain, gauges to calibrate water pipes or standard army bases, staff or scepter decorations, a toy to throw and catch on a stick, or simply a geometric sculpture. Among these speculations, some deserve attention.

A popular hypothesis these days for the purpose of the dodecahedra is that they were used as knitting tools to make gloves. Whether it solves the mystery or not, the YouTube video by Martin Hallett, who tested his idea with a 3D printed replica of a Roman dodecahedron and some experimental archaeology, has inspired others to try out this knitting method to make their own hand warmers.

This idea could explain the different sizes of the dodecahedra – making gloves of different sizes – and the purpose of the holes – to form the glove’s fingers.

However, one of the most accepted theories is that the Roman dodecahedron was used as a measuring device, more precisely as a range measuring an object on the battlefield. The hypothesis is that the dodecahedron was used for calculating the trajectories of projectiles. This could explain the different sized holes in the pentagrams.

A similar theory involves dodecahedra as a surveying and levelling device. However, neither of these theories has been supported by any proof and exactly how the dodecahedron could be used for these purposes has not been fully explained.

Or Maybe they were Astronomical Tools, Religious Relics or Toys?

One of the more interesting theories is the proposal that dodecahedra were astronomic measuring instruments for determining the optimal sowing date for winter grain.

According to G.M.C. Wagemans, “the dodecahedron was an astronomic measuring instrument with which the angle of the sunlight can be measured and thereby one specific date in springtime, and one date in the autumn can be determined with accuracy. The dates that can be measured were probably of importance for the agriculture”.

Nevertheless, opponents of this theory have pointed out that use as a measuring instrument of any kind seems to be prohibited by the fact that the dodecahedra were not standardized and come in many sizes and arrangements.

Another unproven theory claims that the dodecahedra are religious relics, once used as sacred tools for the druids of Britannia and Caledonia. However, there is no written account or archaeological evidence to support this view. Could it be that this strange item was simply a toy or a recreational game for legionnaires, during the war campaigns?

Some sources suggest they were the central objects in a bowl game similar to that of our days, with these artefacts used as markers and the players throwing stones to land them in the holes within the dodecahedra.

A Roman Icosahedron Adds to the Mystery

Another discovery deepens the mystery about the function of these objects. Some time ago, Benno Artmann discovered a Roman icosahedron (a polyhedron with 20 faces), misclassified as a dodecahedron on just a superficial glance, and put away in a museum’s basement storage. The discovery raises the question about whether there are many other geometric artefacts of different types – such as, icosahedra, hexagons, octagons – yet to be found in what was once the significant Roman Empire.

Despite the many unanswered questions, one thing is certain, the Roman dodecahedra were highly valued by their owners. This is evidenced by the fact that a number of them were found among treasure hoards, with coins and other valuable items. We may never know the true purpose of the Roman dodecahedra, but we can only hope that advances in archaeology will unearth more clues that will help solve this ancient enigma.