Tests Underway to Solve Enigma of Naked Cerne Abbas Giant

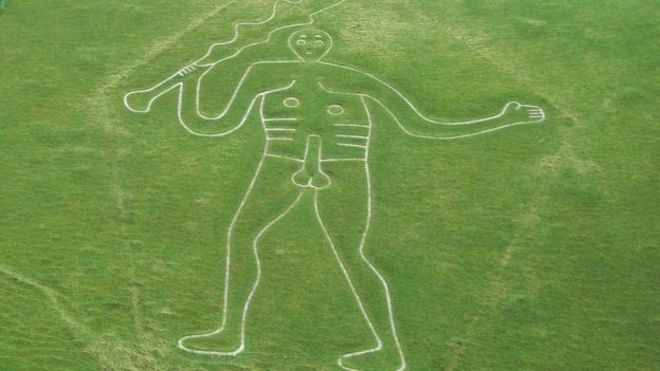

For the first time, archaeologists attempt to establish the age of the mysterious Cerne Abbas Giant. The Cerne Abbas Giant is a 55 m nude chalk figure brandishing a giant club overlooking Cerne Abbas village in Dorset, England.

The origins and purpose of Britain’s largest chalk hill figure remain shrouded in mystery. The giant chalk figure was gifted to the National Trust in 1920 by the Pitt-Rivers family.

The charity and Gloucestershire University also conduct research to determine the age of the giant. Archeologists have excavated small trenches to enable samples of soil to be extracted from points on the giant’s elbows and feet.

Professor Phillip Toms from Gloucestershire University will attempt in the coming weeks to date the samples using a technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL).

Martin Papworth, a senior archaeologist at the National Trust, said: ‘The OSL technique is commonly used to determine when mineral grains in the soil were last exposed to sunlight.

‘It was used to discover the age of the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire in the 1990s, which was found to be nearly 3,000-years-old – even more ancient than we had expected.

‘We’re expecting the results of the tests in July. It is likely that the tests will give us a date range, rather than a specific age, but we hope they will help us better understand, and care for, this famous landmark.’

Gordon Bishop, chairman of the Cerne Historical Society, said villagers were eagerly awaiting the results.

‘Although there are some who would prefer the giant’s age and origins to remain a mystery, I think the majority would like to know at least whether he is ancient or no more than a few hundred-years-old,’ he said.

‘Whichever may be the case, he is unique.’

In a separate analysis, environmental archaeologist Mike Allen will analyze soil samples containing the microscopic shells of land snails to learn more about the site’s past.

‘There are 118 species of snails in Britain and many of them are habitat-specific, so their preserved shells can help us establish what a landscape was like at a certain time, and to track changes in land use over time,’ he said.

‘They should help us to discover whether the giant was created on a grazed chalk hillside, or whether people purposely cleared scrub to prepare the land for the figure.’

Last year, the giant was refreshed for the first time in 11 years, with a team of volunteers hammering in 17 tonnes of new chalk by hand to counteract weathering and keep the giant visible for miles around.

Theories as to the purpose of the giant are unclear. Everything from it being an ancient spirituality symbol or likeness of Greco-Roman hero Hercules to a caricature of Oliver Cromwell, with the club a reference to repressive rule and the phallus a mockery of his puritanism, have been put forward as suggestions.

Local folklore has long held it to be a fertility aid and the earliest recorded mention of the giant dates from 1694.

![Scottish storms unearth 1,500-year-old Viking-era cemetery Scottish Islands were once inhabited by native Picts people only, a Celtic-language speaking group, similar to the natives that live on what is now Scotland. Some powerful storms on the Orkney Islands in Scotland have now unearthed ancient human bones in a Pictish and Viking cemetery dated back to about 1,500 years ago. Volunteers are now placing sandbags and clay around, in order to protect the damage to the ancient Newark Bay cemetery on Orkney’s largest island. The site is dating back to the middle of the sixth century when the Orkney Islands were occupied by native Pictish people. Picts or Norse? The cemetery was used for about 1,000 years, and numerous burials from the ninth to the 15th century were Norsemen or Vikings who had seized the Orkney Islands from the Picts. Now, storm waves are destroying the low cliff where the ancient site is located, Peter Higgins from the Orkney Research Center for Archaeology (ORCA), said. “Every time we have a storm with a bit of a south-easterly [wind], it really gets in there and actively erodes what is just soft sandstone,” Higgins explained. Approximately 250 skeletons were taken out of the cemetery about 50 years ago, but researchers do not know how far the site extends from the beach. They believe that hundreds of Pictish and Norse bodies are still buried there. “The local residents and the landowner have been quite concerned about what’s left of the cemetery being eroded by the sea,” Higgins said. Uncovered bones are usually either coated with clay to protect them or removed from the site after their positions are thoroughly labeled, so it is rather unusual for bones to end up on the beach, he explained. Researchers do not know yet of the exposed bones belong to Picts or Vikings, as no burial objects or funeral clothes were spotted, and the bodies were buried four of five layers under the surface. Cultural Transition Historians claim that the first Norse immigrants to the Orkney Islands established there in the late eighth century, leaving a rising new monarchy in Norway. They used the Orkney Islands to begin their own voyages and Viking raids, and ultimately, all the islands were ruled by the Norse, according to The Scotsman. The relationship between the Picts and the Norse on the Orkney Islands is highly argued by scholars. They cannot know for sure whether the Norse took over by force, or were settlers who traded and entered marriage with the Picts. However, now, the ancient cemetery at Newark Bay may help researchers answer their questions. “The Orkney Islands were Pictish, and then they became Norse,” Higgins said. “We’re not really clear how that transition happened, whether it was an invasion, or people lived together. This is one of the few opportunities we’ve got to investigate that.” A part of the scientific work on the remains would require testing genetic material from the ancient bones, which might demonstrate that some people living on the Orkney Islands today are successors of people who lived there more than 1,000 years ago. “We’re fairly confident that we’re going to find that some local residents are related to people in the cemetery,” Higgins said.](https://archaeology-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/stroms-1.jpg)