El Pital: A Massive Ancient Port City Home to 150 Pyramids

The remains of a huge, ancient port city believed to have flourished for 500 years during the decline of the Roman Empire have been discovered on Mexico’s Gulf Coast, the National Geographic Society announced Thursday.

With more than 150 earthen pyramids and other buildings, the biggest 100 feet high, the port seems to have been North America’s largest coastal city 1,500 years ago. The site, in the state of Veracruz, has been named El Pital for a nearby town.

Although digging has not begun at the site, an examination of the surface has already yielded artefacts and information that establish the city’s importance as a multiethnic political, commercial and agricultural centre from AD 100 to 600.

El Pital could provide important clues to gaps in ancient Mexican history in areas bordering the seats of the Mayan and Aztec empires, said American archaeologist S. Jeffrey K. Wilkerson of the Institute for Cultural Ecology of the Tropics in Tampa, Fla. He is directing the exploration, which is partly funded by National Geographic.

El Pital residents probably traded with their contemporaries at Teotihuacan, the site of the famous pyramids north of the capital that was built by a civilization that predated the Aztecs.

The city is likely to have been an early rival of El Tajin, a later city 40 miles away that until now was the biggest archaeological site in northern Veracruz. El Pital appears to have been larger than El Tajin, controlling an area that included more than 40 square miles of suburbs and farmland and probably influencing an area several times that large.

The discovery could also have significant ecological implications because the ancient civilization seems to have supported more than 20,000 people–similar to the population of the area today–using farming techniques less harmful to the environment than the intensive chemical agriculture now practised there.

“The (population) density we’re seeing far exceeds anything that preceded it in this area and even those that follow until the end of the 20th Century,” Wilkerson said. “Something special was going on technologically that allowed that to happen and that has not occurred in the intervening 1,500 years.”

The fields around El Pital were made highly productive by some of the largest earth-moving projects of their time. Canals were dug to drain wetlands or to channel fresh water into rich estuaries that brackish water would otherwise have left infertile.

Residents also appear to have constructed an artificial island to guard the two slow-moving rivers that provided access to their city from the Gulf of Mexico. One of those rivers is the Nautla, Mexico’s 26th-largest river, notable because it floods every year, like the ancient Nile, leaving farmers a layer of rich silt.

The city’s demise may have been connected to a megacycle of El Nino, a climatic phenomenon that resulted in six months a year of the cold, windy rains known as nortes , Wilkerson theorized.

Some cocoa farmers still lived in the region at the time of the Spanish conquest, but the disease had mainly wiped them out by the end of the 16th Century. The jungle reclaimed the area until plantation owners cleared it again in the 1930s and 1940s.

Today’s farmers rely on chemicals to fertilize plantations in what is now one of Mexico’s most important banana and citrus regions. Those chemicals have stained ancient ceramic fragments–whose varied patterns led scientists to believe that the area was multiethnic–and even obsidian, an extremely dense volcanic material seldom penetrated, Wilkerson said.

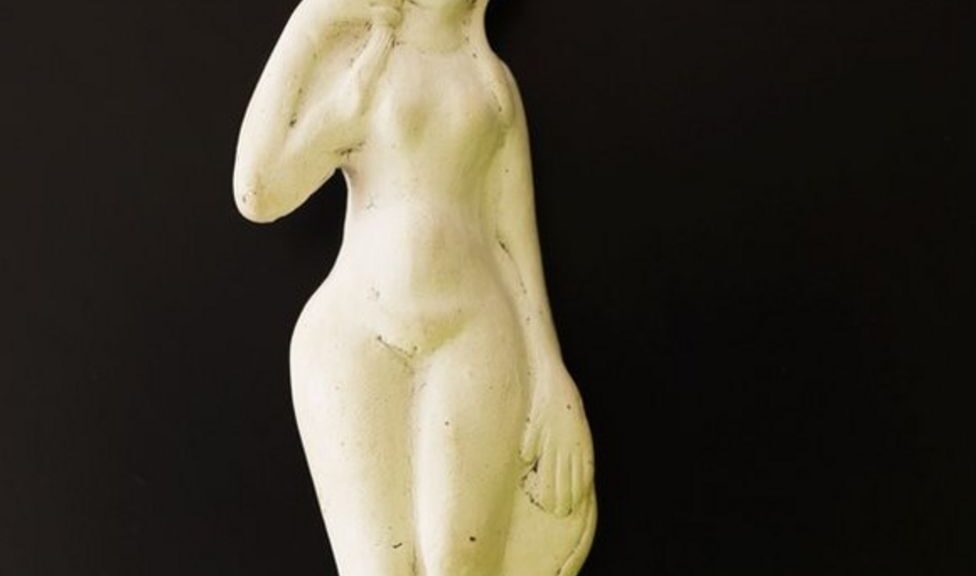

Besides everyday ceramics, archaeologists have found a mask that resembles the image of the ancient rain god Tlaloc and a four-inch clay head believed to depict a sacrificed ballgame player. Residents of El Pital seem to have been major fans of ballgames: Eight courts have already been identified in the area.

“This is an extensive site with huge monuments for that period,” said Enrique Nalda, technical secretary of Mexico’s National Institute of Archeology and History, which granted Wilkerson a permit to explore the El Pital area.

Ironically, Wilkerson discovered El Pital because the institute nearly two years ago refused to allow him to continue working in an area farther upriver, where he has carried out investigations over the last three decades.