An Ancient Papyrus Reveals How The Great Pyramid of Giza Was Built

Stones of up to fifteen tonnes were shipped to a man-made port on wooden boats across the Nile. It has been one of the major enigmas of the world for centuries: how did a simple culture with no sophistication build Giza’s Great Pyramid.

The earliest and only survivor of the Ancient World’s Seven Wonders? It was the tallest man-made building on Earth for almost 4,000 years, at 146 metres high.

Archaeologists also discovered the diary of Merer, an official involved in the building of Giza’s great pyramid, in what is regarded by some to be one of the greatest discoveries in Egypt in the 21st century.

The 4,500-year-old papyrus is the oldest in the world and describes how wooden boats and ingenious system of waterworks transported blocks of limestones and granite weighing up to 15 tonnes from 13 kilometres away. In it, Merer (which means beloved) describes how he and a crew of 40 elite workmen shipped the stones downstream from Tura to Giza along the Nile River.

In the last few years, the papyrus and other archaeological excavations have revealed new information about how the pyramids were constructed. Here are some of the findings uncovered in Nature of Things documentary Lost Secrets of the Pyramid.

Water was harnessed to transport huge stones.

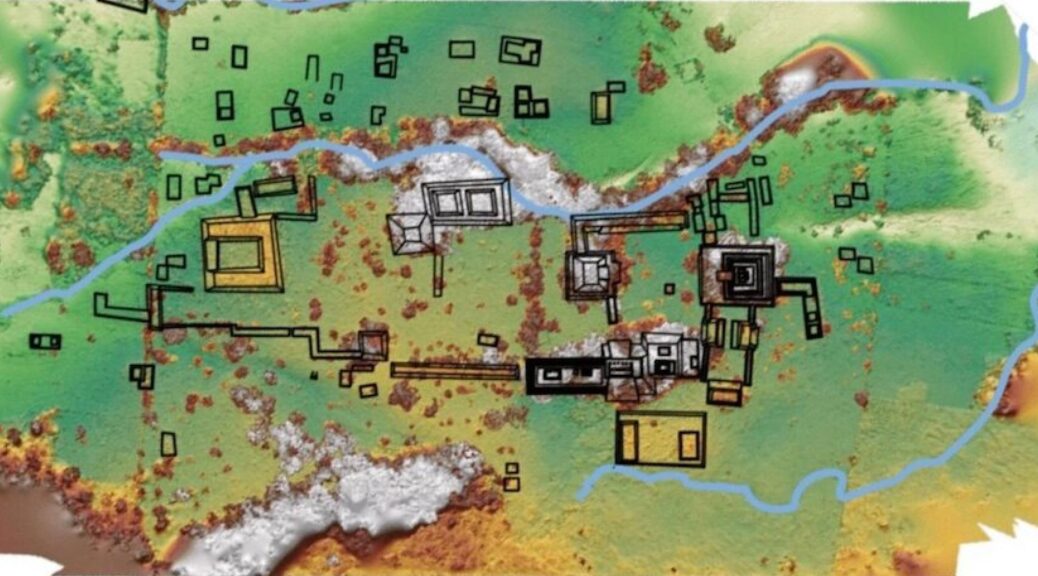

Every summer, when the Nile flooded, giant dykes were opened to divert water from the river and channel it to the pyramid through a manmade canal system creating an inland port which allowed boats to dock very close to the worksite — just a few hundred metres away from the growing pyramid.

The construction of artificial ports was a huge turning point for Egyptians, opening up trade and new relationships with people from distant lands.

Wooden boats built with rope instead of nails.

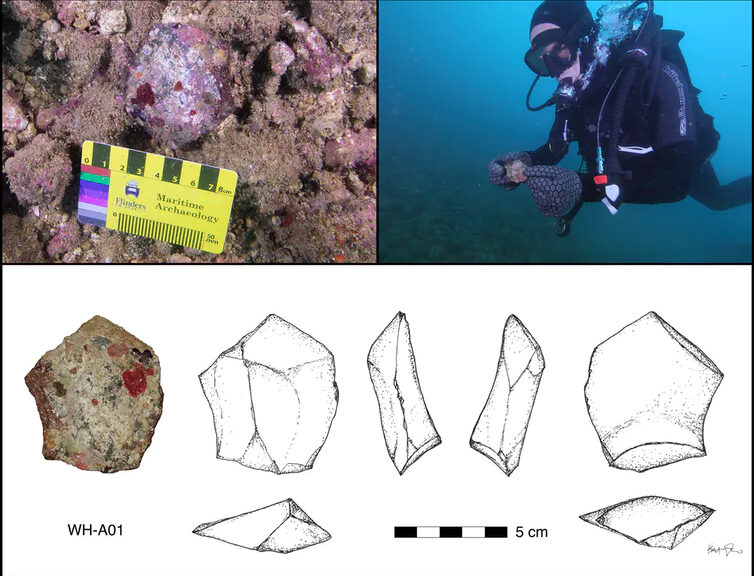

The limestone was carried along the River Nile in wooden boats built with planks and rope that were capable of hauling two-and-a-half tonne stones.

Using ancient tomb carvings and the remains of an ancient dismantled ship as a guide, archaeologist Mohamed Abd El-Maguid has recreated one Egyptian boat from scratch.

3D scans of the ship planks revealed that the boats were full of holes that lined up perfectly with each other. Instead of nails or wood pegs, these boats were sewn together with rope like a giant jigsaw puzzle.

With 1,000 holes and five kilometres of rope the new boat was assembled and Abd El-Maguid and in Secrets of the Pyramid, attempts to re-create every step of Merer’s journey down the Nile with two-tonne limestone rock.

These boats were rowed carefully with the current down the Nile to the worksite. Once the rocks were unloaded, the wind helped propel the vessel back to the quarry.

Workers were valued and lived nearby in a huge settlement

Archaeologist Mark Lehner has uncovered artefacts that provide evidence of a vast settlement that held as many as 20,000 people. Average workers lived in huge dormitories, but team leaders like Merer lived in relative luxury with homes of their own.

Thousands of tiny bits of detritus of everyday life reveal that these hungry workers were well taken care of. An entire city was formed near the pyramid site to provide food and drink.

For most of the workers, building the pyramids was a source of prestige; these people have valued servants of the state.

Workers belonged to teams

Ankhhaf, Pharoah Khufu’s half-brother is mentioned in Merer’s diary and is thought to have been in charge of the operation. He divided the workforce into ‘phyles’ teams of 40 men — of which someone like Merer oversaw.

Artefacts with team names on them have been discovered by archaeologist Pierre Tallet at a remote desert outpost in Wadi Al-Jarf about 250 kilometres away. Merer’s phyle was called “The Followers of the Boat named after the Snake on its Figurehead.”

Four phyles formed a gang of elite labourers. Each team has specific roles in the construction of the pyramid or the transportation of materials to the worksite.

Thousands of men, working together for over 20 years, succeeded in building the tallest, heaviest structure on earth. They transformed the landscape, and in doing so, also created a new society which archaeologist Mark Lehner says is the real achievement, “Once they had put all these systems and all this infrastructure in place there was no going back. They became more important than the pyramid itself and set Egyptian civilization off on a course for the next two or three millennia.”