Ancient Maya Worshipped ‘Batman God’ 2,500 Years Ago

A peculiar religious cult grew up among the Zapotec Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico in 100 A.D.

The dangerous cave-dwelling bat creature – which the Zapotecs believed represented night, death, and sacrifice – was eventually adopted into the pantheon of the K’iche’, a Mayan tribe inhabiting modern-day Guatemala and Honduras. The legends of the bat god were later recorded in Popol Vuh, a Mayan sacred book.

Camazotz, which translates to ‘death bat‘ (K’iche’ word ‘kame‘ means “death”, while ‘sotz’ means “bat”), originated deep in Mesoamerican mythology as a dangerous cave-dwelling bat creature.

The K’iche’ identified the bat-deity with their god Zotzilaha Chamalcan, the god of fire. Camazotz, which inhabited Xibalbá, is also commonly depicted holding a sacrificial knife in one hand and a human heart or sacrificial victim in the other.

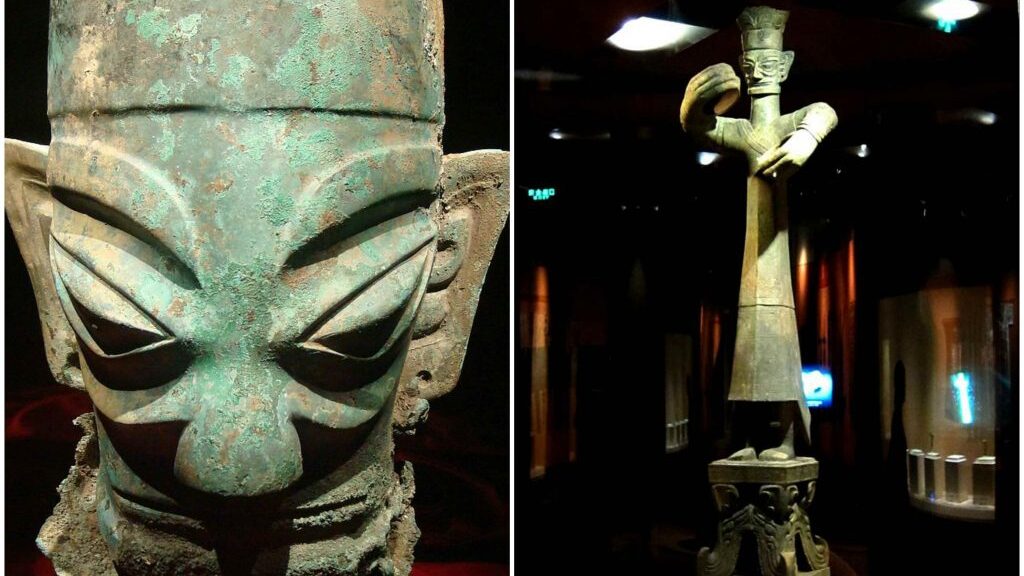

Templo Mayor, located in downtown Mexico City, has an adjacent museum that displays artifacts and renditions of items from the Mesoamerican civilizations. The top floor of this museum contains a recreated statue of Camazotz.

One of the most prominent and commonly mentioned features of the Camazotz is “a nose the shape of a flint knife”, which could be an exaggerated interpretation of the nose-leaf possessed by members of the Phyllostomidae or leaf-nosed bats.

Traces

In 1988, a fossil of a giant vampire bat was discovered in the Mongas province of Venezuela. The bat was larger than the modern vampire bat by 25% and was dubbed D. Draculae. Its recent age and large range suggest that the bat could have co-existed with the K’iche’, giving rise to the legends of the Camazotz.

In 2000, a tooth from D. Draculae was found in Argentina – much farther south of the modern range of the Desmodus genus. The latest age found for a D. Draculae site is circa 1650 AD. These dates make it very possible that D. Draculae coexisted with humans in South America and Central America.

The common vampire bat, D. Rotundus, has an eight-inch wingspan. Since D. Draculae was 25% larger, it would have required more blood and probably would have attacked larger animals – and possibly even humans. It is undoubtable that an attack by a rare giant bat would give rise to legends of supernatural monsters.

In 2014, Warner Brothers gathered as many as 30 artists to reinterpret Batman on the occasion of its 75th anniversary. Christian Pacheco, one of the artists, recalled that Batman is not the first reference of an enigmatic anthropomorphic being with a man’s body and a bat’s head. It is was indeed the feared Camazotz.

Pacheco’s Yucatán [Mexico]-based design firm Kimbal made a replica of the bust with which Bruce Wayne disguises the character and molded it with Maya motifs and references to the ancient Camazotz.

The designed gave a heads up to many people that the very first batman can be traced back to the ancient Maya, more than 2,500 years ago.

In the Popol Vuh, Camazotz was a common name making reference to the bat-like monsters that the Mayan twin heroes Hunahpú and Ixbalanque stumbled across, during their trials in Xibalbá, the Mayan underworld.

Camazotz was said to attack victims by the neck and decapitate them. In the Popol Vuh, it is recorded that the deity decapitated Hunahpú and is also one of the four animal demons responsible for wiping out mankind during the age of the first sun.

National Geographic Writes:

“The Maya hero twins were placed inside a bat house—a cave filled with death bats, called Camazotz by the Maya.

The bats had snouts like blades, which they used to kill people and animals. To escape, the twins crawled inside their blowguns, and all night long the bats terrorized them. Toward dawn, one of the twins said he would check to see if it was safe to leave. He raised his head out of his gun—and promptly had it cut off by a Camazotz.”

In 2018, it was reported that two species of carnivorous bats were found from southern Mexico to Bolivia and Brazil – the woolly bat (the toothy, hungry bats with long bunny-like ears and a lance-shaped nose leaf found in a Maya temple) and the spectral bat. According to biologist Rodrigo Medellín, woolly and spectral bats are likely the bats described in the Popol Vuh:

“These bats do the same thing. They stalk their prey, land on them with half-spread wings, locking them with the thumb claws, and deliver a death bite to the back or top of the head. Camazotz was not an invention.”