14,000-Year-Old Ancestor of Native Americans Identified in Russia

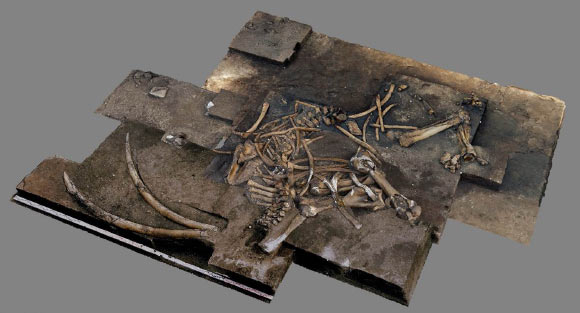

Since the Upper Paleolithic, modern humans have lived near Baikal Lake, and left a rich archeological record behind.

The region’s ancient genomes also uncovered multiple genetic turnovers and admixture events, indicating that the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age was facilitated by human mobility and complex cultural interactions. The nature and timing of these interactions, however, remains largely unknown.

The reports of 19 newly sequenced human genomes, including one of the oldest ones recorded by the area of Lake Baikal, are presently in a new study published in the journal Cell.

Led by the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the study illuminates the population history of the region, revealing deep connections with the First Peoples of the Americas, dating as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period, as well as connectivity across Eurasia during the Early Bronze Age.

The deepest link between peoples

“This study reveals the deepest link between Upper Paleolithic Siberians and First Americans,” says He Yu, the first author of the study. “We believe this could shed light on future studies about Native American population history.”

Past studies have indicated a connection between Siberian and American populations, but a 14,000-year-old individual analyzed in this study is the oldest to carry the mixed ancestry present in Native Americans.

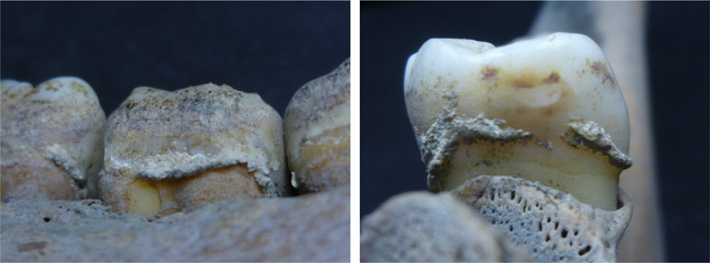

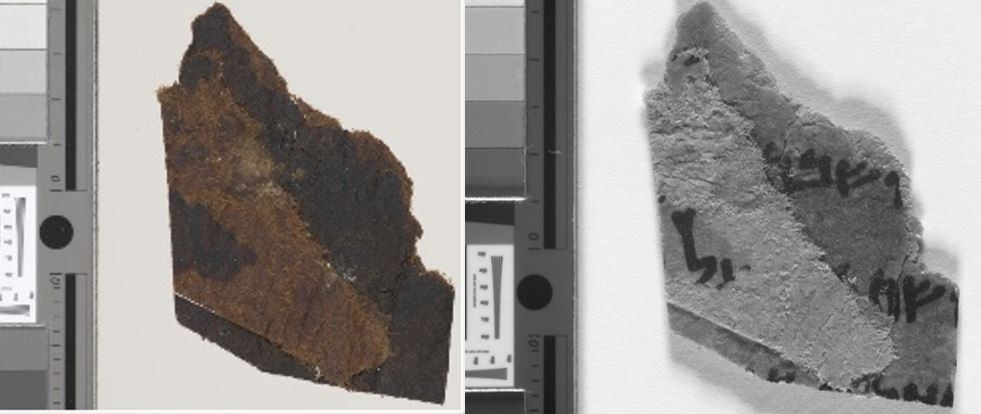

Using an extremely fragmented tooth excavated in 1976 at the Ust-Kyahta-3 site, researchers generated a shotgun-sequenced genome enabled by cutting edge techniques in molecular biology.

This individual from southern Siberia, along with a younger Mesolithic one from northeastern Siberia, shares the same genetic mixture of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) and Northeast Asian (NEA) ancestry found in Native Americans and suggests that the ancestry which later gave rise to Native Americans in North- and South America was much more widely distributed than previously assumed.

Evidence suggests that this population experienced frequent genetic contacts with NEA populations, resulting in varying admixture proportions across time and space.

“The Upper Paleolithic genome will provide a legacy to study human genetic history in the future,” says Cosimo Posth, a senior author of the paper. Further genetic evidence from Upper Paleolithic Siberian groups is necessary to determine when and where the ancestral gene pool of Native Americans came together.

A web of prehistoric connections

In addition to this transcontinental connection, the study presents connectivity within Eurasia as evidenced in both human and pathogen genomes as well as stable isotope analysis.

Combining these lines of evidence, the researchers were able to produce a detailed description of the population history in the Lake Baikal region.

The presence of Eastern European steppe-related ancestry is evidence of contact between southern Siberian and western Eurasian steppe populations in the preamble to the Early Bronze Age, an era characterized by increasing social and technological complexity. The surprising presence of Yersinia pestis, the plague-causing pathogen, points to further wide-ranging contacts.

Although spreading of Y. pestis was postulated to be facilitated by migrations from the steppe, the two individuals here identified with the pathogen were genetically northeastern Asian-like. Isotope analysis of one of the infected individuals revealed a non-local signal, suggesting origins outside the region of discovery.

In addition, the strains of Y. pestis the pair carried is most closely related to a contemporaneous strain identified in an individual from the Baltic region of northeastern Europe, further supporting the high mobility of those Bronze age pathogens and likely also people.

“This easternmost appearance of ancient Y. pestis strains is likely suggestive of long-range mobility during the Bronze Age,” says Maria Spyrou, one of the study’s co-authors.

“In the future, with the generation of additional data we hope to delineate the spreading patterns of plague in more detail,” concludes Johannes Krause, senior author of the study.