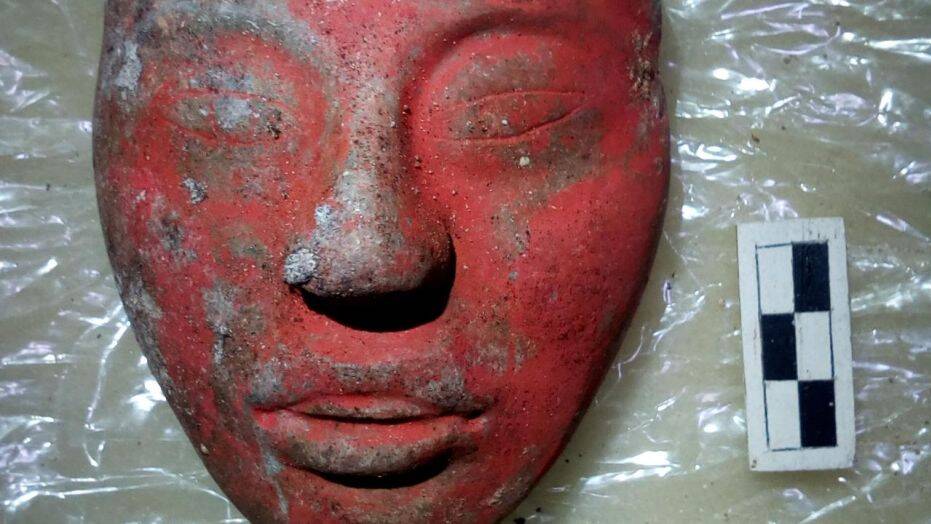

17th-century Dutch merchant ship off southern England have recovered a 30-foot-long wooden carving of a mustachioed warrior

Archeologists greeted a carving of the face of a moustachio warrior as they lifted part of a huge shipwreck in the 17th century in the English Channel The head was carved into the 28 ft long section of the rudder of a Dutch trading ship that sunk nearly 400 years earlier in Poole, Dorset.

Its accidental discovery by a dredger led to six years of underwater investigations, which prompted experts to hail the find as the most significant since the Mary Rose. Divers found the sizable carving covering the stern and bow castle of the 130ft-long merchant vessel, which would have been one of the largest of its kind on the seas at the time.

It was decked out with opulent carvings of mermen whose eye sockets would have been decorated with precious stones. Other baroque-style carvings, similar to the one on the rudder, were also found on parts of the ship including the gunports.

Marine archaeologists from Bournemouth University have already recovered scores of artifacts from the vessel that is known as the Swash Channel Wreck after the area of sea where it sunk.

And after being given a grant of £500,000 from English Heritage, the team completed the recovery of the five-tonne wooden rudder that had become separated from the main hull.

Divers spent seven days digging the rudder from out of the sea bed and placing a large steel frame around it, similar to the operation that raised the Mary Rose in 1982.

It was then towed four miles into Poole Harbour where today it was hoisted onto the quayside by a crane in front of the excited team of archaeologists.

The baroque facial carving at the end of the rudder shows a military man wearing a classical helmet. It will be constantly sprayed with special chemicals for the next two years to help conserve it.

The rudder will then put on display at Poole Museum alongside other artifacts recovered from the wreckage. Dave Parham, a senior lecturer in marine archaeology at Bournemouth University, said: ‘Before now we had just seen the rudder underwater where you could only make out a few feet of it at a time.

‘So to see it in daylight in all its glory is really quite spectacular.

‘It is a very large and impressive item itself so you can imagine how spectacular this merchant vessel would have looked.

‘Its discovery is an extremely significant one and has given way to one of the largest shipwreck investigations within the UK.’

Unlike the Mary Rose, little is known of the Swash Channel Wreck, including its identity. Tests on the oak wood from it have dated the felling of the timber to 1628 and from forests on the Dutch/German border. Analysis of some of the recovered artifacts dates to the middle of the 17th century.

This has led the experts to believe the vessel was an armed Dutch trading ship that was either going to or returning from the Mediterranean or the Far East. It is thought it hit a sandbank in the approaches to Poole Harbour and water flooded its bilges. The ship is then believed to have rolled over and sunk in 22ft of water.

Mr. Parham said: ‘It would have been a very big vessel for its day and the whole vessel would have been a spectacular work of art.

It was a sign of prestige and wealth. It was making a statement, showing how great and wonderful the owners were. They would have been a large Dutch conglomerate, similar to the East India Company.

‘It would not have been a million miles from a 17th-century version of the Titanic, although the Titanic was ornate for the passengers and not for those on the outside.

‘We think it was a Dutch trading ship and would have taken high-quality European goods like tweed to the Far East and traded them for things like exotic spices.

It was either going out or coming back when it sank outside of Poole Harbour. We have received a grant to fund the recovery of all the material that is at risk of erosion.

So far the team has brought up artifacts including five baroque carvings, ceramic pieces, leather shoes, copper and pewter plates and cups, and a bronze compass divider. They have also recovered animal bones of sheep and cows that would have fed the crew.

Mr. Parham said: ‘Last month we spent seven days excavating beneath the rudder in order to put strops around it and lift it into a steel frame.

It was then moved four miles to the quayside in Poole and lifted out of the water. We have no idea who the male carving on the rudder might be. It is a mustachioed man with a classical helmet on so it is depicting a military man of some sort. About 40 percent of the port side of the wreck lies intact on the sea bed but it will be too costly an operation to recover that.