8th Century Jain Idol Found By Farmer While Ploughing Fields In Southern India

A significant discovery was made in India by a farmer working on his land. He uncovered a remarkable Jain statue dated back a thousand years. Traces of a temple are believed to have also been found. The discoveries contribute to the knowledge of the history of the region by researchers as it was an important Jainism center.

Oggu Anjaiah is a farmer from the village of Kotlanarsimhulapalli, in Karimnagar district, which is in the state of Telangana in the south of India. He was plowing his land before the monsoon when he came across something large.

Oggu had plowed up an ancient statue. He alerted other villagers and they immediately realized that it was something sacred. According to Telangana Today, local people “performed pujas to the statue”, meaning acts of worship.

Speculation Over the Identity of Jain Statue

The local authorities were alerted to the find and they visited the site of the discovery. According to The News Minute, experts believe the statue could represent the 24th Tirthankara, Vardhamaana Mahaveer.

He is an important figure, a saint, and a spiritual teacher in Jainism and was crucial in the development of the religion. He is regarded as one of the twenty-four saints of the faith and is still worshiped by Jains to this day. Jainism is an ancient Indian religion that teaches that salvation can be achieved by a life of non-violence and renunciation.

“The idol is reportedly in a Dhyana Mudra (meditation posture)”, reports The News Minute. There is some debate as to the identity of the figure depicted.

Karimnagar Assistant Director of the Archaeology Department, Nagaraju, told The News Minute that “the statue could either be of Adinathudu (Vrushabanathudu) [also known as Rishabhanatha], the first Tirthankara (spiritual teacher) of Jain or the 24th Tirthankara, Vardhamaana Mahaveer.” What is clear, however, is that the statue is of great historic and religious importance.

Possible Remains of Jain Temple Found Nearby

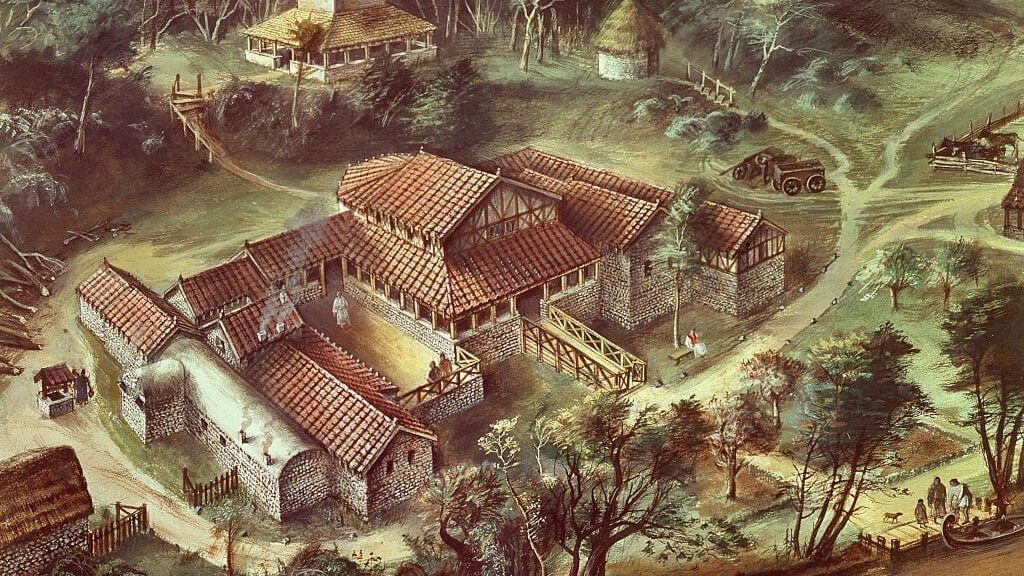

State archaeologists “found the imprints of a structure (Jain temple) and decided to take up excavation in the half-acre area,” according to Telangana Today.

The structure was similar to modern Jain places of worship and was probably decorated with many reliefs and statues. It is likely that monks from the monastery buried the idol here, though the reasons remain unknown. Nagaraju, the Assistant Director of the Archaeology Department, told The News Minute that the site is some 11 miles (15 km) from a “hillock called Bommalagutta, where there was a Jain monastery.”

Some years ago an idol belonging to the 23rd Jain Theerthankara called Parshvanatha was found in the same fields”, reports The Hindu.

The find is believed to date from the 8 th and 9 th century AD when the Rastrakuta dynasty ruled this region. Their abandoned capital is located not far from the village.

The Rastrakutas adopted Jainism, becoming patrons of the religion, and sponsored the building of temples as part of their policy of promoting the faith. After the fall of this dynasty, Jainism went into decline and Hinduism grew in popularity. During Muslim rule, members of the religion were often discriminated against and there are few adherents of the religion in this part of India today.

Dispute Over Final Resting Place for Ancient Jain Sculpture

Assistant Director Nagaraju, told The Teleangan Times that “more sculptures and structure of Jains may be found at the spot.” The authorities want to move the statue to a regional museum, but the local villagers have so far prevented this.

They want to erect a shrine or temple in the village in order to house the statue. As a result of this stand-off, the idol is now being kept under a tree near where it was found.

The recent discovery has once again shed some light on the history of Jainism. It has also helped to revive interest in this ancient faith, which now has over 4 million followers in India. A Jain trust has also committed to building a temple in the area if they can secure land.