World’s oldest wooden statue is TWICE as old as Stonehenge

Gold prospectors first discovered the so-called Shigir Idol at the bottom of a peat bog in Russia’s Ural mountain range in 1890. The unique object—a nine-foot-tall totem pole composed of ten wooden fragments carved with expressive faces, eyes and limbs and decorated with geometric patterns—represents the oldest known surviving work of wooden ritual art in the world.

More than a century after its discovery, archaeologists continue to uncover surprises about this astonishing artefact. As Thomas Terberger, a scholar of prehistory at Göttingen University in Germany, and his colleagues wrote in the journal Quaternary International in January, new research suggests the sculpture is 900 years older than previously thought.

Based on extensive analysis, Terberger’s team now estimates that the object was likely crafted about 12,500 years ago, at the end of the Last Ice Age. Its ancient creators carved the work from a single larch tree with 159 growth rings, the authors write in the study.

“The idol was carved during an era of great climate change, when early forests were spreading across a warmer late-glacial to postglacial Eurasia,” Terberger tells Franz Lidz of the New York Times.

“The landscape changed, and the art—figurative designs and naturalistic animals painted in caves and carved in rock—did, too, perhaps as a way to help people come to grips with the challenging environments they encountered.”

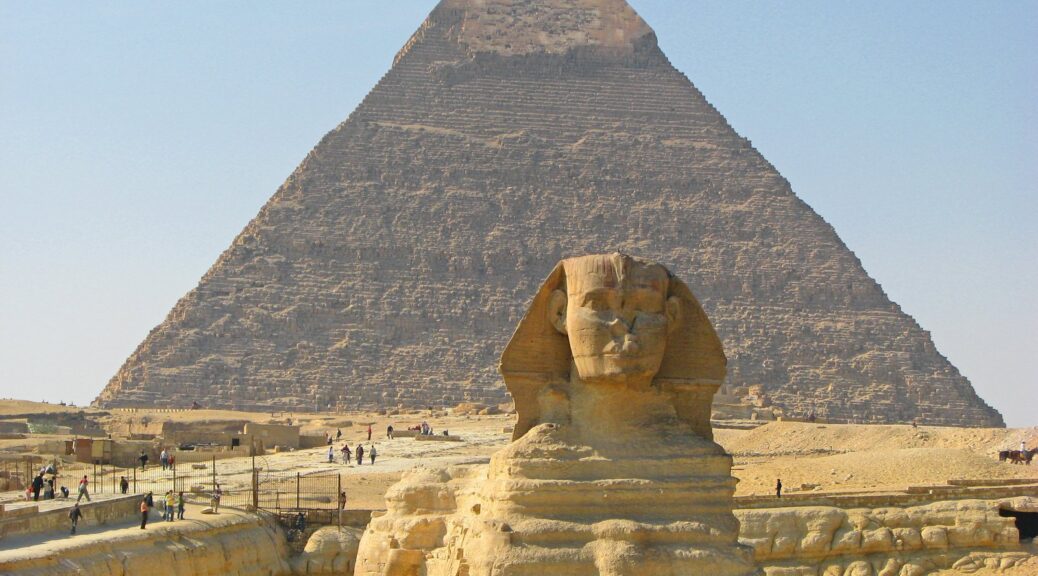

According to Sarah Cascone of Artnet News, the new findings indicate that the rare artwork predates Stonehenge, which was created around 5,000 years ago, by more than 7,000 years. It’s also twice as old as the Egyptian pyramids, which date roughly 4,500 years ago.

As the Times reports, researchers have been puzzling over the age of the Shigir sculpture for decades. The debate has major implications for the study of prehistory, which tends to emphasize a Western-centric view of human development.

In 1997, Russian scientists carbon-dated the totem pole to about 9,500 years ago. Many in the scientific community rejected these findings as implausible: Reluctant to believe that hunter-gatherer communities in the Urals and Siberia had created art or formed cultures of their own, says Terberger to the Times, researchers instead presented a narrative of human evolution that centered European history, with ancient farming societies in the Fertile Crescent eventually sowing the seeds of Western civilization.

Prevailing views over the past century adds Terberger, regarded hunter-gatherers as “inferior to early agrarian communities emerging at that time in the Levant. At the same time, the archaeological evidence from the Urals and Siberia was underestimated and neglected.”

In 2018, scientists including Terberger used accelerator mass spectrometry technology to argue that the wooden object was about 11,600 years old. Now, the team’s latest publication has pushed that origin date back even further.

As Artnet News reports, the complex symbols carved into the object’s wooden surface indicate that its creators made it as a work of “mobiliary art,” or portable art that carried ritual significance.

Co-author Svetlana Savchenko, the curator in charge of the artifact at the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum of Local Lore, tells the Times that the eight faces may contain encrypted references to a creation myth or the boundary between the earth and sky.

“Woodworking was probably widespread during the Late Glacial to early Holocene,” the authors wrote in the 2018 article. “We see the Shigir sculpture as a document of a complex symbolic behaviour and of the spiritual world of the Late Glacial to Early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of the Urals.”

The fact that this rare evidence of hunter-gatherer artwork endured until modern times is a marvel in and of itself, notes Science Alert. The acidic, antimicrobial environment of the Russian peat bog preserved the wooden structure for millennia.

João Zilhão, a scholar at the University of Barcelona who was not involved in the study, tells the Times that the artefact’s remarkable survival reminds scientists of an important truth: that a lack of evidence of ancient art doesn’t mean it never existed.

Rather, many ancient people created art objects out of perishable materials that could not withstand the test of time and were therefore left out of the archaeological record.

“It’s similar to the ‘Neanderthals did not make art’ fable, which was entirely based on the absence of evidence,” Zilhão says. “Likewise, the overwhelming scientific consensus used to hold that modern humans were superior in key ways, including their ability to innovate, communicate and adapt to different environments. Nonsense, all of it.”